Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| EX-31.4 - EXHIBIT 31.4 - 9 METERS BIOPHARMA, INC. | tv496133_ex31-4.htm |

| EX-31.3 - EXHIBIT 31.3 - 9 METERS BIOPHARMA, INC. | tv496133_ex31-3.htm |

| EX-10.2 - EXHIBIT 10.2 - 9 METERS BIOPHARMA, INC. | tv496133_ex10-2.htm |

| EX-10.1 - EXHIBIT 10.1 - 9 METERS BIOPHARMA, INC. | tv496133_ex10-1.htm |

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549

FORM 10-K/A

(Amendment No. 1)

(Mark One)

| þ | ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017

OR

| ¨ | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the transition period from ________________ to ________________

Commission file number 001-37797

INNOVATE BIOPHARMACEUTICALS, INC.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

| Delaware | 27-3948465 | |

| (State or other jurisdiction of | (I.R.S. Employer | |

| incorporation or organization) | Identification No.) |

8480 Honeycutt Road, Suite 120

Raleigh, North Carolina 27615

(Address of principal executive offices, including zip code)

(919) 275-1933

(Registrant’s telephone number, including area code)

SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT:

| Title of each class | Name of each exchange on which registered |

| Common Stock $0.0001 Par Value | The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC |

SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No þ

Indicate by check mark if the issuer is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ¨ No þ

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes þ No ¨

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes þ No ¨

Indicate by check mark if the disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of the Registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or an amendment to this 10-K. ¨

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

| Large accelerated filer | ¨ | Accelerated filer | ¨ | |

| Non-accelerated filer | ¨ | Smaller reporting company | þ | |

| (Do not check if smaller reporting company) | Emerging growth company | þ |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. þ

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ¨ No þ

The aggregate value of common stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant as of June 30, 2017, the last business day of the registrant’s most recently completed second fiscal quarter, was $3,878,345 (based on the last reported closing sale price on the Nasdaq Capital Market on that date of $4.90 per share).

As of March 12, 2018, the registrant had 25,691,680 shares of common stock, par value $0.0001 per share, issued and outstanding.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Form 10-K/A

(Amendment No. 1)

| EXPLANATORY NOTE | ||

| PART I | ||

| ITEM 1. | BUSINESS | 3 |

| PART IV | ||

| ITEM 15. | EXHIBITS AND FINANCIAL STATEMENT SCHEDULES | 36 |

| SIGNATURES | 41 | |

| 2 |

Innovate Biopharmaceuticals, Inc. (the “Company”) is filing this Amendment No. 1 on Form 10-K/A (this “Amendment”) to amend the Company’s Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017, as filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) on March 14, 2018 (the “Form 10-K”). This Amendment is being filed solely to (i) update “Item 1. Business” to reflect comments received from the SEC Staff on the Company’s Form 8-K filed with the SEC on February 2, 2018, as amended and previously reflected therein, (ii) re-file Exhibits 10.1 and 10.2 to the Form 10-K (the “Exhibits”) and (iii) amend Part IV, “Item 15. Exhibits, Financial Statement Schedules” of the Form 10-K, including revising the Exhibit Index. The Exhibits, as re-filed on this Amendment, restore certain provisions that had previously been redacted in accordance with the Company’s application for confidential treatment in response to comments received from the SEC Staff. In addition, as required by Rule 12b-15 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, new certifications by the Company’s principal executive officer and principal financial officer are filed as exhibits to this Amendment.

No attempt has been made in this Amendment to modify or update the other disclosures presented in the Form 10-K. This Amendment does not reflect events occurring after the filing of the Form 10-K (i.e., those events occurring after March 14, 2018) or modify or update disclosures that may be affected by subsequent events. Such subsequent matters are addressed in subsequent reports filed with the SEC. Accordingly, this Amendment should be read in conjunction with the Form 10-K and the Company’s other filings with the SEC.

Merger of Monster Digital, Inc. and Innovate Biopharmaceuticals Inc.

On January 29, 2018, Monster Digital, Inc. (“Monster”) and privately held Innovate Biopharmaceuticals Inc. (“Private Innovate”) completed a reverse recapitalization in accordance with the terms of the Agreement and Plan of Merger and Reorganization, dated July 3, 2017, as amended (the “Merger Agreement”), by and among Monster, Monster Merger Sub, Inc. (“Merger Sub”) and Private Innovate, which changed its name in connection with the transaction to IB Pharmaceuticals Inc. (“IB Pharmaceuticals”). Pursuant to the Merger Agreement, Merger Sub merged with and into IB Pharmaceuticals with IB Pharmaceuticals surviving as the wholly owned subsidiary of Monster (the “Merger”). Immediately following the Merger, Monster changed its name to Innovate Biopharmaceuticals, Inc. (“Innovate”). In connection with the closing of the Merger, Innovate’s common stock began trading on the Nasdaq Capital Market under the ticker symbol “INNT” on February 1, 2018. Prior to the Merger, Monster was incorporated in Delaware in November 2010 under the name “Monster Digital, Inc.”

Except as otherwise noted or where the context otherwise requires, as used in this report, the words “we,” “us,” “our,” the “Company” and “Innovate” refer to Innovate Biopharmaceuticals, Inc. as of and following the closing of the Merger on January 29, 2018 and, where applicable, the business of Private Innovate prior to the Merger. All references to “Monster” refer to Monster Digital, Inc. prior to the closing of the Merger.

Overview

Prior to the Merger, Monster’s primary business focus was the design, development and marketing of premium products under the “Monster Digital” brand for use in high-performance consumer electronics, mobile products and computing applications.

After the Merger, we are a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company developing novel medicines for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases with unmet needs. Our pipeline includes drug candidates for celiac disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Our lead program, INN-202 (larazotide acetate or larazotide) is entering Phase 3 registration trials, targeted for the second half of 2018, and has the potential to be the first-to-market therapeutic for celiac disease, an unmet medical need, which affects an estimated 1% of the North American population or approximately 3 million individuals. Celiac patients have no treatment alternative other than a strict lifelong adherence to a gluten-free diet, which is difficult to maintain and can be deficient in key nutrients. Additionally, current FDA labeling standards allow up to 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten in “gluten-free” labelled foods, which are sufficient to cause celiac symptoms in many patients, including abdominal pain, abdominal cramping, bloating, gas, headaches, ataxia, ’‘brain fog’’ and fatigue. Long-term ramifications of celiac disease include enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), osteoporosis and anemia.

| 3 |

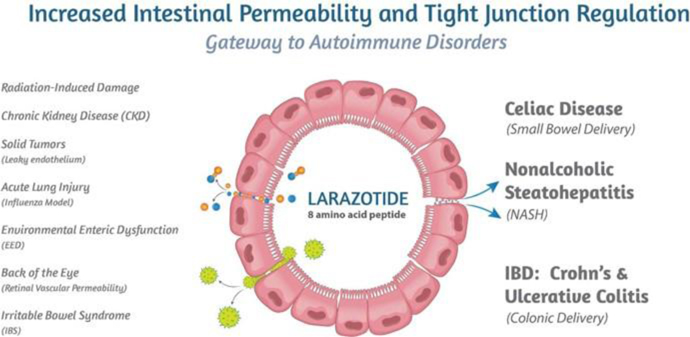

Figure 1: Larazotide’s mechanism of action is applicable to multiple diseases.

Larazotide is an 8-amino acid peptide orally administered in a capsule which has been tested in more than 500 celiac patients with statistically significant improvement in celiac symptoms. The FDA has granted larazotide Fast Track Designation for celiac disease. Larazotide’s safety profile was similar to placebo primarily because larazotide is not systemically absorbed into the blood circulation. Additionally, larazotide’s mechanism of action (MoA) as a tight junction regulator is a new approach to treating autoimmune diseases, such as celiac disease. Pre-clinical studies have shown larazotide causes a reduction in permeability across the intestinal epithelial barrier, making it the only drug candidate known to us which is in clinical trials with this MoA. Increased intestinal permeability underlies several diseases in addition to celiac disease, including NASH, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), among others (Figure 1). We are engaging in multiple research collaborations to expand larazotide’s clinical indications with a shorter time to proof-of-concept.

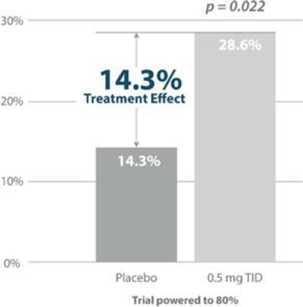

With the release of the Phase 2b trial data in 342 celiac patients at the 2014 Digestive Disease Week (DDW) conference, larazotide became the first and the only drug for the treatment of celiac disease (published data), which met its primary efficacy endpoint with statistical significance. The Phase 2b data showed statistically significant (p=0.022) reduction in abdominal and non-GI (headache) symptoms as measured by the CeD PRO. After a successful End-of-Phase 2 meeting with the FDA, which confirmed the regulatory path forward, we expect to launch the Phase 3 registration program later this year with topline data expected by 2019.

Larazotide is being investigated as an adjunct to a gluten-free diet for celiac patients who continue to experience symptoms despite adhering to a gluten-free diet. Due to the difficulty of maintaining a gluten-free diet due to lack of easy access to and the higher cost of gluten-free foods, contamination from gluten as well as social pressures, it is estimated that more than half the celiac population experiences multiple, potentially debilitating, symptoms per month. A study from the UK indicates that more than 70% of patients diagnosed with celiac disease consume gluten either intentionally or inadvertently (Hall et al. 2013).

| 4 |

Another indication for which larazotide is currently being developed is NASH. NASH is an unmet need disease affecting approximately 5%-6% of the US adult population. There are currently several drugs in development; however, to our knowledge, none have larazotide’s MoA. We are developing a proprietary formulation of larazotide, INN-217, for efficient delivery to the intestine. INN-217 has the potential to reduce the transport of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is produced by gram negative bacteria in the gut, from the intestinal lumen to the liver via the portal circulation. Several studies have shown the link between NASH and increased levels of LPS, which translocates across an inflamed, “leaky” epithelial barrier to the liver thus directly damaging liver cells via an inflammatory cascade. INN-217 can potentially decrease the flux of LPS across the leaky epithelial barrier, which is known to play an important role in the pathogenesis of NASH. Since none of the NASH drugs in development currently target intestinal permeability, INN-217 has the potential to affect NASH alone and work synergistically with late stage NASH drugs in development, which are primarily focused on metabolic targets such as farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC).

Figure 2: LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) is a toxin produced by intestinal bacteria and can translocate via the leaky epithelial barrier to the liver and damage liver cells. Thus LPS has been implicated in the pathogenesis of NASH.

| 5 |

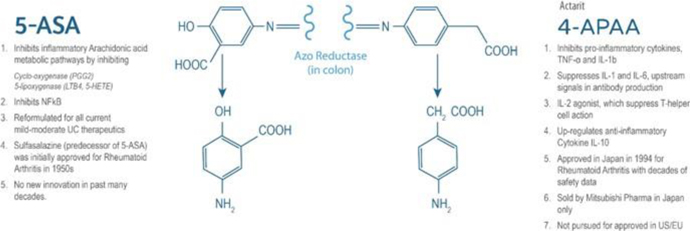

INN-108, is in development for the treatment of mild-to-moderate UC. INN-108 is expected to be delivered orally using an azo-bonded pro-drug approach linking mesalamine or 5-ASA (5-amino salicylic acid) to 4-APAA (approved as Actarit in Japan in 1994 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis). After having completed a successful Phase 1 trial at currently approved doses of mesalamine, INN-108 is expected to enter a proof-of-concept Phase 2 trial. The azo-bond protects INN-108 (Figure 2) from the low pH in the stomach, allowing it to transit to the colon where the UC lesions are primarily located. In the colon, the azo bond is broken enzymatically by azoreductases, leading to the separation of mesalamine and 4-APAA which has a synergistic anti-inflammatory effect. Although the majority of patients present with mild-to-moderate UC, the focus of drug development has been in moderate-to-severe UC with little innovation or drug development for mild-to-moderate UC. The mainstay of treatment for mild-to-moderate UC continues to be various oral reformulations of mesalamine such as Shire’s Lialda (approved 2007) and Pentasa (approved 1993), Allergan’s Asacol HD (approved 2008) and Valeant/Salix’s Apriso (approved 2008).

We also own the global rights to INN-329, a proprietary formulation of secretin, a peptide hormone which is used to improve visualization in magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) procedures. Secretin is a 27-amino acid long hormone which rapidly stimulates release of pancreatic secretions, thus improving visualization of the pancreatic ducts during imaging procedures.

| 6 |

Our Strategy

Our goal is to become a leading biopharmaceutical company by developing novel therapeutics that have the potential to transform current treatment paradigms for patients and to address unmet medical needs. We are currently pursuing the development of drugs for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases that target established biological pathways. The critical components of our strategy are as follows:

| • | Advance INN-202 (larazotide) for celiac disease into Phase 3 clinical trials. Our highest clinical priority is to initiate the Phase 3 trials for larazotide for the treatment of celiac disease. We had a successful End-of-Phase 2 meeting with the FDA in 2017. With the guidance and agreement reached with the FDA, we plan to initiate our Phase 3 trials during the second half of 2018. |

| • | Accelerate development of INN-217 (larazotide) for NASH. Increased intestinal permeability leads to LPS translocation to the liver and is one of the key recognized pathogenic factors in NASH. Larazotide’s mechanism of action to decrease intestinal permeability could thus have a therapeutic effect in NASH. We plan to develop larazotide alone and in combination with select NASH therapies in clinical trials with the potential for synergistic therapeutic benefit. |

| • | Further the study INN-108 for Ulcerative colitis . We are currently developing plans to initiate the proof of concept Phase 2 trials for INN-108 for the treatment of UC. We plan to initially develop INN-108 for mild-to-moderate UC in adults. |

| • | Further the study of INN-289 (larazotide) for Crohn’s disease. The mechanism of action of larazotide to decrease intestinal permeability can have a therapeutic effect in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In an IL-10 knockout animal model, larazotide showed promising data which can position it for a proof-of-concept study using a proprietary formulation of larazotide, INN-289, alone and in combinations with select approved immunological therapies. |

| • | Seek partnerships to commercialize late stage pipeline drugs. With large addressable markets, such as celiac disease, we plan to seek out partners with established presences and histories of successful commercialization. |

| • | Leverage and protect our existing intellectual property portfolio and secure patents for additional indications. We intend to continue to expand our intellectual property protection strategy, grounded in securing composition of matter patents and method of use patents for newer indications. We plan to develop newer formulations for the product candidates for other indications and improved performance of existing indications. |

| • | In-license additional intellectual property and pipeline drugs to expand our presence in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases . In addition to broadening our current pipeline through indication expansion, we plan to explore expansion of our product pipeline through in-licensing, strategic partnerships and product acquisitions, as we did in 2016 by in-licensing of larazotide from Alba Therapeutics Corporation. We expect that future pipeline expansion decisions will be based on the unmet medical needs in autoimmune and inflammatory disease areas including, but not limited to, celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, the commercial opportunity, and the ability to rapidly develop and commercialize a product candidate. |

| • | Leverage the expertise of our management team and network of scientific advisors and key opinion leaders . We are led by a strong management team with deep experience in drug development, collaborations, operations, and corporate finance. Our team has been involved in a broad spectrum of R&D activities leading to successful outcomes, including FDA approvals and drug launches. We will continue to leverage the collective experience and talent of our management team, network of leading scientific experts, and key opinion leaders to strategize and implement our development and eventually our commercialization strategy. |

| • | Out-license our non-core assets/indications and establish research collaborations . From time to time, we review our internal research priorities and therapeutic focus areas and may decide to out-license non-core assets/indications that arise from current and future available data. We may seek research collaborations that leverage the capabilities of our core assets to monetize and expand upon the breadth of opportunities that may be accessible through our drug candidates. |

| • | Outsource capital intensive operations . We plan to continue to outsource capital intensive operations, including most clinical development and all manufacturing operations of our product candidates, to facilitate the rapid development of our pipeline by using high quality specialist vendors and consultants in a capital efficient manner. |

| 7 |

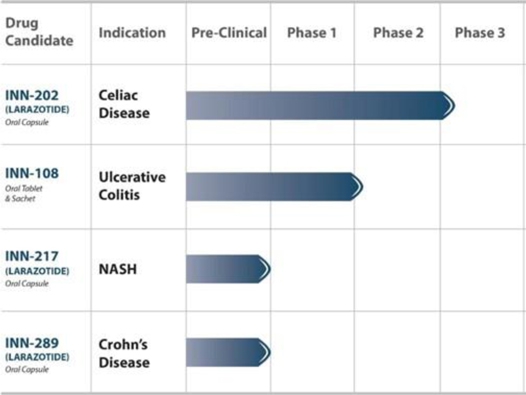

Our Drug Product Pipeline

Our current pipeline is focused on clinical stage assets with large markets and unmet medical needs. We continue to leverage additional proof-of-concept work for larazotide to expand into additional indications, including NASH, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. The following table summarizes key information about our pipeline of drug product candidates to date (Table 1):

Table 1: Our key pipeline products are clinical stage and address large markets with chronically dosed therapies.

INN-202 (Larazotide) for Celiac Disease

Larazotide is being developed for the treatment of celiac disease and has successfully completed a Phase 2b trial showing statistically significant reduction in abdominal and non-GI (headache) symptoms. We are planning to launch the Phase 3 trials in the second half of 2018.

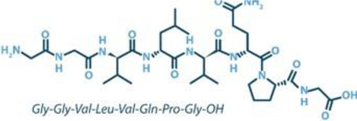

Larazotide is an orally administered, locally acting, non-systemic, synthetic 8-amino acid (Figure 3), tight junction regulator being investigated as an adjunct to a gluten-free diet in celiac disease patients who still experience persistent GI symptoms despite being on a gluten-free diet. Because of larazotide’s lack of absorption into the blood circulation, we believe that fewer complications, if any, are likely to develop for individuals taking chronically dosed lifetime medication.

The larazotide drug product is an enteric coated drug product formulated as enteric coated multiparticulate beads filled into hard gelatin capsules for oral delivery. The enteric coating is designed to allow the bead particles to bypass the stomach and release larazotide upon entry into the small intestine (duodenum). A mixed bead formulation is used to allow partial release of larazotide upon entry into the duodenum and to release the remaining larazotide approximately 30 minutes later. In clinical trials, larazotide has been dosed 15 minutes before meals allowing time for its effect in the small bowel before exposure to gluten.

| 8 |

Figure 3: Larazotide acetate is an 8-amino acid peptide in an oral capsule using a proprietary formulation

Larazotide’s Mechanism of Action

In research studies supportive of the mechanism of action, larazotide has been shown to stimulate recovery of mucosal barrier function via the regulation of tight junctions both in vitro and in vivo , including in a celiac disease mouse model (Gopalakrishnan, 2012). In doing so, it is proposed that larazotide reduces the symptoms associated with celiac disease.

In several autoimmune diseases, this increased intestinal permeability or paracellular leakage allows increased exposure to a triggering antigen and a consequent inflammatory response, the characteristics of which are determined by the particular disease and the genetic makeup of the individual. A new paradigm for autoimmune diseases is that there are three contributing factors to the development of disease:

| 1. | A genetically susceptible immune system that allows the host to react abnormally to an environmental antigen; |

| 2. | An environmental antigen that triggers the disease process; and |

| 3. | The ability of the environmental antigen to interact with the immune system. |

Larazotide regulates tight junction opening triggered by both gluten and inflammatory cytokines, thus reducing uptake of gluten. Larazotide also disrupts the intestinal permeability-inflammation loop, and has been shown to reduce symptoms associated with celiac disease.

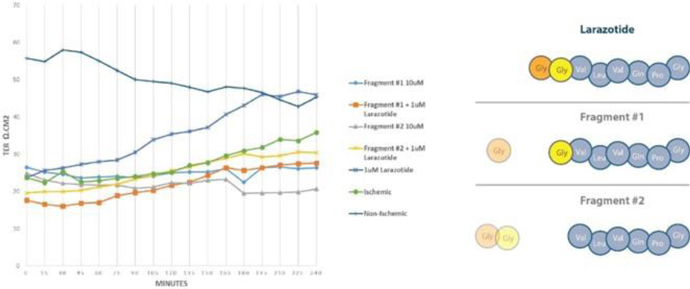

Larazotide’s Dose Response

Previously published in vitro work using Caco-2 cells has shown a linear dose response for larazotide in reducing permeability of the epithelial barrier by tightening the tight junctions (Gopalakrishnan, 2012). In several clinical trials, larazotide has exhibited clinical benefit by reducing celiac symptoms at lower doses while inhibition of this activity occurs at the higher doses. To better understand this observation, Dr. Anthony Blikslager from North Carolina State University evaluated the pharmacology of larazotide at the luminal surface of the small intestine in an ex vivo porcine model. A section of the porcine intestine was ligated, placed in an Ussing chamber and changes in permeability were measured by electrical resistance. Multiple experiments demonstrated that following an ischemic insult causing increased intestinal permeability, full length larazotide is capable of restoring intestinal wall integrity to that of the non-ischemic control. Subsequently, it was discovered that a specific aminopeptidase located within the brush borders of the intestinal epithelium cleaves larazotide into two fragments which lack either one or both N-terminus glycine (G) residues ( GG VLVQPG). Both cleaved fragments, GVLVQPG and VLVQPG, do not decrease intestinal permeability. Moreover, when these two fragments are administered in combination with the active full-length larazotide, they inhibit larazotide’s activity to restore intestinal wall integrity or reduce permeability. These data demonstrate that higher doses of larazotide lead to local buildup of breakdown fragments, which then compete with and block activity of larazotide after threshold concentration is reached. The in vitro experiments using Caco-2 monolayers did not show the same pharmacology and dose response because they lack the brush border and therefore lack the aminopeptidase which cleaves larazotide. These data also provide an explanation for the clinical observations of an optimal lower dose of larazotide, which avoids the reservoir of competing inactive fragments generated at high doses of larazotide.

| 9 |

Figure 4: An aminopeptidase in the brush border cleaves larazotide into two fragments, #1 and #2, which then act as inhibitors of larazotide

Figure 5: Illustrative effect of gluten ingestion, breakdown to gliadin which can cross a “leaky” epithelial barrier in the small bowel thus activating the intestinal-inflammatory loop and leading to symptoms and villous atrophy.

The Intestinal Barrier, Tight Junctions, and Intestinal Permeability

The intestine is one of the largest interfaces between a person and his or her environment, and an intact intestinal barrier is essential in maintaining overall health. An important function of the intestinal barrier is to regulate the trafficking of macromolecules between the environment and the host. Together with gut-associated lymphoid tissue and the neuroendocrine network, the intestinal epithelial barrier controls the equilibrium between tolerance and immunity to non self-antigens. When the finely tuned trafficking of macromolecules is dysregulated, both intestinal and extra-intestinal autoimmune disorders can occur in genetically susceptible individuals (Figure 5).

| 10 |

Transcellular fluxes (through the cell membrane) allow nutrients and small molecules to enter the cell from the luminal side of the intestine and exit on the serosal side (internal milieu). Paracellular fluxes (between cells) in contrast are limited by size and charge constraints imposed by the tight junctions between epithelial cells. The paracellular pathway is the key regulator of intestinal permeability to larger more complex macromolecules that may be immunogenically significant.

Intestinal epithelial cells adhere to each other through junction complexes. The tight junction, also referred to as zonula occludens, represents the major barrier to diffusion within the paracellular space between intestinal cells. Multiple proteins that make up the tight junction have been identified including occludin, claudin family members, and junctional adhesion protein (JAM). These interact with cytosolic proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3) that function as adaptors between the tight junction proteins and actin and myosin contractile elements within the cell. Acting together, they open and close the paracellular junctions between cells. It is now apparent that tight junctions are dynamic structures that are involved in developmental, physiological, and pathological processes.

The role of tight junction dysfunction in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases is under active investigation. Many autoimmune populations have increased intestinal permeability, and it is believed that this may play a fundamental role in the development of autoimmunity. In susceptible populations, the opening of tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells may lead to exposure to oral antigens via paracellular transport and a consequent autoimmune response. A wide range of gastrointestinal and systemic inflammatory diseases are associated with abnormal intestinal permeability including celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s disease and UC), and ankylosing spondylitis.

Summary of Key Clinical Trials using Larazotide in Celiac Disease

Larazotide has been administered to humans in seven clinical trials. These include three Phase 1 trials: (two trials in healthy subjects and a Phase 1b proof of concept (POC) trial in subjects with celiac disease), two Phase 2 gluten challenge studies in subjects with controlled celiac disease, and additionally two Phase 2 trials in subjects with active celiac disease (Table 2). After the Phase 1 studies, larazotide was tested to explore which endpoint would be suitable for celiac disease. After looking at permeability changes in the gut, which turned out to be highly variable in a large trial setting, and then mucosal healing, which likely requires a longer-term study, symptom reduction showed the most consistent and reliable reduction both in a gluten challenge and a ’‘real-life’’ trial. Importantly, after exposure in more than 800 subjects, the safety profile of larazotide remained similar to placebo due to its lack of absorption into the bloodstream, which we believe is an important advantage for a chronically dosed drug.

The initial Investigational New Drug Application (IND) for the treatment of celiac disease was filed with the FDA by Alba Therapeutics Corporation (Alba) on 12 August 2005 for the use of larazotide acetate (INN-202). The IND was transferred from Alba to Innovate effective March 8, 2016. Over the course of the seven clinical studies, 5 patients experienced a serious adverse event, of which 2 received placebo and 3 received larazotide. These events included inflammation of the gallbladder, gall stones, depression, allergic reaction to penicillin, and appendicitis. We do not believe that any of these events were considered related to treatment with study medication.

| Trial | Study Date | Clinical Trial | No. of Subjects | |||

| -001 | 2005 | Phase 1: Single Escalating Doses in Healthy Volunteers | 24 | |||

| -002 | 2005-06 | Phase 1b: Multiple Dose POC in Celiac Patients – Gluten Challenge | 21 | |||

| -003 | 2006 | Phase 1: Multiple Escalating Dose in Volunteers | 24 | |||

| -004 | 2006-07 | Phase 2a: Multiple Dose POC in Celiac Patients Gluten Challenge 2 weeks | 86 | |||

| -006 | 2008 | Phase 2b: Dose Ranging, in Celiac Patients Gluten Challenge, 6 weeks | 184 | |||

| -011 | 2008-09 | Phase 2b: POC and Dose Ranging in Active Celiac Patients | 105 | |||

| -06B | 2008 | Phase 2b: Similar to -006, in Celiac Patients | 42 | |||

| -012 | 2011-13 | Phase 2b: Multiple dose in Celiac patients with Symptoms on a Gluten-Free Diet | 342 |

Table 2: Significant drug exposure in more than 800 subjects in multiple clinical trials consistently showed a safety profile similar to placebo, which we believe is an important advantage for chronic lifetime administration.

| 11 |

Clinical Trial (’006) Results Revealed Key Insight into Symptom Reduction as a Primary Endpoint

A Phase 2b study with a gluten challenge (CLIN1001-006) was conducted in 184 subjects with well-controlled celiac disease on a gluten-free diet. Subjects were randomized to one of four treatment groups, (placebo, 1 mg, 4 mg, or 8 mg larazotide) and asked to take treatment 15 minutes prior to each meal (TID). Nine hundred (900) mg of gluten was taken with each meal. Subjects remained on their gluten-free diet throughout the duration of the trial. The trial results revealed key insights into how to move the program forward by focusing on reduction of symptoms. The 1-mg dose prevented the development of gluten-induced symptoms as measured by GSRS (a patient-reported outcome (PRO) devised and validated by AstraZeneca), and all drug treatment groups had lower anti-transglutaminase antibody levels than the placebo group. Results of pre-specified secondary endpoints suggest that larazotide reduced antigen exposure as manifested by reduced production of anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) levels and immune reactivity towards gluten and gluten-related gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects with celiac disease undergoing a gluten challenge.

Figure 6: The overall trial designs for Phase 2b and Phase 3 are similar with a screening period followed by 12 weeks of randomization to larazotide vs. placebo.

Figure 7: Responder Rate Analysis: Larazotide is the only drug in development for celiac disease to meet its primary endpoint with statistical significance as measured by the copyrighted CeD PRO (celiac disease patient reported outcome), an FDA-agreed upon primary endpoint for Phase 3 (shown above). Source: Gastroenterology 2015; 148:1311–1319; p. 1315

Clinical Trial (’012) Met the Primary Endpoint with Statistical Significance (CeD-GSRS/CeD PRO)

The purpose of the ’012 study was to assess the efficacy (reduction and relief of signs and symptoms of celiac disease) of 3 different doses of larazotide (0.5 mg, 1 mg, and 2 mg TID) versus placebo for the treatment of celiac disease in adults as an adjunct to a gluten-free diet. Larazotide or placebo which was administered TID, 15 minutes prior to each meal. After a screening period, subjects were asked to continue following their current gluten-free diet into a placebo-run in phase for 4 weeks after which they were randomized to drug versus placebo. Subjects maintained an electronic diary capturing: daily symptoms celiac disease patient reported outcome (CeD-PRO), weekly symptoms (CeD-GSRS), bowel movements (BSFS), and a self-reported daily general well-being assessment (Figure 6).

| 12 |

The primary endpoint of average on-treatment CeD GSRS score throughout the treatment period was met at the 0.5 mg TID dose. In addition, a number of pre-specified secondary and exploratory endpoints, such as symptomatic days and symptom-free days, collectively demonstrated that a dose of 0.5 mg TID was superior to placebo and higher doses of larazotide. No difference was observed between the two higher dose levels (1 and 2 mg TID) or placebo, suggesting a narrow dose range around the 0.5mg dose which seems to correlate with pre-clinical data.

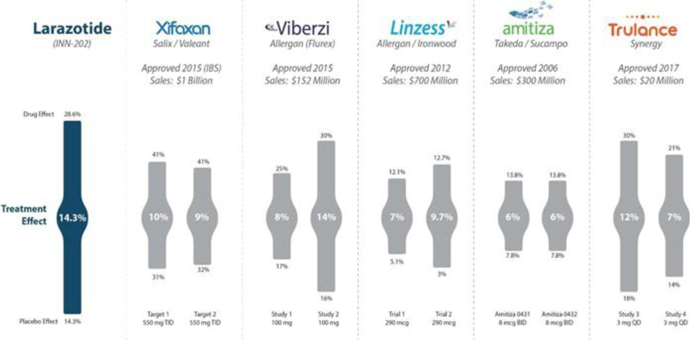

Figure 8: Treatment effect of larazotide from the Phase 2b trial (’012) compared to approved IBS/CIC drugs with varying treatment effects mostly in the mid to high single digit range. Source: Gastroenterology 2015; 148:1311–1319; p. 1315 and FDA Drug Labels

The CeD PRO, a copyrighted PRO created specifically for celiac disease and wholly owned by us, showed a statically significant (p=0.022) treatment effect of 14.3% (drug responder rate minus placebo responder rate). Although to our knowledge there are no celiac drugs approved as a comparator, the treatment effect was greater than several other GI dugs approved for IBS and chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) which use a similar clinical trial design (Figure 8).

| 13 |

Path Forward to Phase 3 Trials

After a successful End-of-Phase 2 meeting with the FDA, agreements were reached on the key aspects of the Phase 3 trials. The FDA agreed on using the previously validated CeD PRO as the primary endpoint with two doses of larazotide which bracket the range of efficacy in previous trials. Two Phase 3 trials with a size of about 500 patients each would allow for more than a 90% power to replicate the Phase 2b trial results. Most other criteria, such as inclusion, exclusion and site selection/coordination, are expected to remain similar to the ’012 Phase 2b trial.

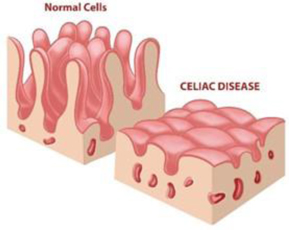

About Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is a genetic autoimmune disease triggered by the ingestion of gluten-containing foods such as wheat, barley, and rye. Individuals with celiac disease have increased intestinal permeability, commonly referred to as a ’‘leaky’’ gut. This allows macromolecules that normally remain on the luminal side of the intestine to pass through to the serosal side through tight junctions via paracellular diffusion (Figure 9). In the case of celiac disease, this permeability may allow gluten break-down products, the triggering antigens of celiac disease, to reach gut-associated lymphoid tissue(GALT), initiating an inflammatory response. Celiac disease is characterized by chronic inflammation of the small intestinal mucosa that may result in diverse symptoms, malabsorption, atrophy of intestinal villi, and a variety of clinical manifestations.

Figure 9: The epithelial barrier separates the intestinal content from the immune system (lamina propria) and the vasculature.

| 14 |

Figure 10: Intestinal villi atrophy in celiac patients, a characteristic finding upon biopsy of the small intestine.

Large Population — Unmet Need (no drug approved); Serious Long-Term Consequences

Celiac disease affects an estimated 1% of the Western population (Dubé, 2005). Currently, there are no therapeutics available to treat celiac disease, and the current management of celiac disease is a life-long adherence to a gluten-free diet. Changes in dietary habits are difficult to maintain, and foods labeled as gluten-free may still contain small amounts of gluten (up to 20 ppm per FDA labeling standards). Dietary compliance is imperfect in a large fraction of patients (Rostom, 2006) and difficult to adhere to on an ongoing basis (Green, 2007). In a survey conducted in the United Kingdom non-adherence to the gluten-free diet was found to be as high as 70% (Hall, 2013).

There are serious long-term consequences to exposure to gluten in patients with celiac disease, including the risk of developing osteoporosis, stomach, esophageal, or colon cancers, and T-cell lymphoma (Green 2003, Green 2007). The continuous GI symptoms often result in significant morbidity with a substantial reduction in quality of life. In addition, not all patients respond to a gluten-free diet. Patients with known celiac disease may continue to have or re-develop symptoms despite being on a gluten-free diet (Rostom 2006). This suggests a need for a therapeutic agent for the treatment of celiac disease (Green, 2007; Hall, 2013).

Celiac disease represents a model of an autoimmune disorder in which the following elements are known:

| 1. | The triggering environmental factor is glutenin or gliadin, the proline, glutamine and glycine rich glycoprotein fractions of gluten; |

| 2. | There is a close genetic association with HLA haplotypes DQ2 and/or DQ8; and |

| 3. | A highly specific humoral autoimmune response occurs. |

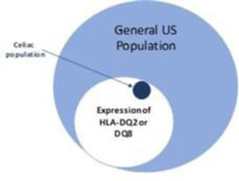

Genetics of Celiac Disease

The high incidence of celiac disease in first degree relatives of celiac patients (10 − 15%) and high concordance rate in monozygotic twins (80%) suggest a strong genetic component. Gliadin deamidation by tissue transglutaminase (tTG) enhances the recognition of gliadin peptides by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ2 and DQ8 T cells in genetically predisposed subjects, which in turn may initiate the cascade of autoimmune reactions responsible for mucosal destruction. This interaction implies that gliadin and/or its breakdown peptides in some way cross the intestinal epithelial barrier and reach the lamina propria of the intestinal mucosa where they are recognized by antigen-presenting cells. The enhanced paracellular permeability of individuals with celiac disease would allow passage of macromolecules through the paracellular spaces with resulting autoimmune inflammation. There is a strong genetic predisposition to celiac disease, with major risk associated with HLA DQ2 (approximately 95% of celiac disease patients) and HLA-DQ8 (approximately 5% of celiac disease patients). The prevalence of celiac disease in the U.S. is estimated to be approximately 1%; however approximately 30% of the general U.S. population is HLA DQ2 positive (Figure 11), indicating that additional factors are involved in the development of celiac disease.

| 15 |

Figure 11: Distribution of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 in the general US population and in celiac disease. Source: J. Clin. Invest. 2007 Jan 2;117(1):41.

In celiac disease, an inflammatory reaction occurs in the intestine that is characterized by infiltration of immune cells in the lamina propria and epithelial compartments with chronic inflammatory cells and progressive architectural changes to the mucosa. Both adaptive and innate branches of the immune system are involved. The adaptive response is mediated by gluten-reactive CD4+ T cells in the lamina propria that recognize gluten-derived peptides when presented by the HLA class II molecules DQ2 or DQ8. The CD4+ T cells then produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon gamma. This results in an inflammatory cascade with the release of cytokines, anti-tTG antibodies, T cells, and other tissue-damaging mediators leading to villous injury and crypt hyperplasia in the intestine. Anti-human tissue transglutaminase (anti-tTG) antibodies are also produced, which form the basis of serological diagnosis of celiac disease.

Anti-tTG Antibodies: Highly Sensitive and Specific Blood-based ELISA Diagnostic Test

The current approach for diagnosis of celiac disease is to use anti-tissue transglutaminase-2 (tTG-2) antibody tests as an initial screen with definitive diagnosis from biopsy of the small intestine mucosa. The diagnosis of celiac disease is confirmed by demonstration of characteristic histologic changes in the small intestinal mucosa, which are scored based on criteria initially put forth by Marsh and later modified. In 2012, the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Guidelines allowed symptomatic children with serum anti-tTG antibody levels ≥10 times upper limit of normal to avoid duodenal biopsies after positive human leukocyte (HLA) test and serum anti-endomysial antibodies.

The need for multiple clinical and laboratory findings to diagnose celiac disease makes monitoring disease progression difficult. International guidelines give standardized definitions and criteria for the diagnosis of celiac disease, however there are not clear standards for follow-up and monitoring of treatment. This is particularly true for celiac patients diagnosed as adults, who respond differently and less completely to a gluten-free diet than do celiac patients diagnosed as children. It is not clear who should perform follow-up of patients with celiac disease and at what frequency but the American College of Gastroenterology suggests that an annual follow-up seems reasonable. Recommendations for monitoring disease progression include assessing symptoms and dietary compliance, and repeating serology tests. Markers of celiac disease progression and improvement that are both validated and provide a timely assessment of disease activity are lacking.

Role of Tissue Transglutaminase in Celiac Disease

Anti-tTG-2 antibodies are produced in the small-intestinal mucosa (Picarelli et al. 1996), where they can bind tTG-2 present in the basement membrane and around blood vessels and form deposits characteristic of the disease. tTG-2 has been implicated in a variety of human disorders including several neurodegenerative conditions and cancer. Transglutaminases (TGs) were first discovered in the 1950s and are a family of enzymes which catalyze Ca2+-dependent post-translational modification of proteins. Of the seven isoforms discovered so far all share the same basic four-domain tertiary structure, with minor variations, although their catalytic mechanism is conserved, resembling that of the cysteine proteases. tTGs cause transamidation, esterification, and hydrolysis, all of which lead to post-translational modifications in the target proteins. Characteristically, tTG’s mediate selective protein cross-linking by forming covalent isopeptide linkages between two target proteins. The resulting cross-linked products in many cases have high molecular masses and are unusually resistant to proteolytic degradation and mechanical strain. As in the case of the gliadin fragments in celiac disease, they are able to pass thru the leaky paracellular pathway from the lumen to the lamina propria , where the immune cells reside and are then activated.

| 16 |

Gliadin fragments, in addition to being rich in proline, also have high glutamine content, which makes them suitable substrates for tTG-2, which targets glutamine residues. For augmented DQ2/8 binding, the conversion of glutamine residues to glutamic acid is catalyzed by tTG-2 as a deamidation reaction. After deamidation, the gliadin peptides become highly negatively charged in key anchor positions, thereby increasing their affinity to the HLA molecules. CD4+ T cells recognize the deamidated gliadin peptides bound to the HLA DQ2 or DQ8 molecules by their T cell receptors, thus activating intestinal inflammation leading to villous atrophy.

Gluten and Food Labeling

Gluten is a complex molecule contained in several grains such as wheat, rye and barley. Gluten can be subdivided into two major protein subgroups according to its solubility in alcohol and aqueous solutions. These subclasses consist of gliadins, soluble in 40 − 70% ethanol and glutenins which are large, polymeric molecules insoluble in both alcohol and aqueous solutions. The gliadins and glutenins can be further subdivided into groups according to their molecular weight. Glutenins can be subdivided into low and high molecular weight proteins, while the gliadin protein family contains α-, β-, γ- and ω- types. Both glutenins and gliadins are characterized by a high amount of prolines (20%) and glutamines (40%) that protect them from complete degradation in the gastrointestinal tract and make them difficult to digest. Currently 31 nine-amino acid peptide sequences in the prolamins of wheat and related species have been defined as being celiac toxic or celiac ’‘epitopes.’’ These epitopes are located in the repetitive domains of the prolamins, which are proline and glutamine-rich, and the high levels of proline make the peptide resistant to proteolysis. In addition, the prolamin-reactive T cells also recognize these epitopes to a greater extent when specific glutamine residues in their sequences have been deamidated to glutamic acid by tTG-2. The immunodominant sequence after wheat challenge corresponds to a well-characterized 33 residue peptide from α-gliadin, ’’33-mer,’’ that is resistant to gastrointestinal digestion (with pepsin and trypsin) and was initially identified as the major celiac toxic peptide in the gliadins.

The FDA finalized a standard definition of ’‘gluten-free’’ in August 2013. As of August 5, 2014, all manufacturers of FDA-regulated packaged food making a gluten-free claim must comply with the guidelines outlined by the FDA ( www.fda.gov/gluten-freelabeling ). A ’‘gluten free’’ claim still allows up to 20 ppm of gluten which leads to more than 100mg/day up to 500 mg/day of gluten exposure. Due to presence of gluten in foods, beer/liquor, cosmetics and household products, exposure is virtually impossible to completely avoid, and with cross-contamination, celiac patients cannot avoid exposure to gluten therefore, making symptoms more frequent than expected.

| CNS | Endocrine | Oncology/Heme | Skin | Other | ||||

| Headaches | Type 1 Diabetes |

Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) |

Dermatitis herpetiformis | Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | ||||

| Gluten ataxia |

Autoimmune Thyroid |

anemia | Alopecia areata |

Reduced bone Density | ||||

| Peripheral neuropathies | Addison’s disease | Vitiligo | Sjogren’s syndrome |

Table 3: Diseases associated with celiac disease

Non-GI Manifestations of Celiac Disease and Co-Morbidities

Headache, Gluten Ataxia: Nervous System Manifestation of Celiac Disease. The association between celiac disease and neurologic disorders has been supported by numerous studies over the past 40 years. While peripheral neuropathy and ataxia have been the most frequently reported neurologic extra-intestinal manifestations of celiac disease a growing body of literature has established headache as a common presentation of celiac disease as well. The exact prevalence of headache among patients ranges from about 30% to 6% (Lebwohl, 2016).

Dermatitis herpetiformis: Skin Manifestation of Celiac Disease. Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an inflammatory cutaneous disease characterized by intensely pruritic polymorphic lesions with a chronic-relapsing course, first described by Duhring in 1884. DH’s only treatment is a strict lifelong gluten-free diet, for achieving and maintaining a permanent control. It appears in around 25% patients with celiac disease, at any age of life, mainly in adults and is a very characteristic clinical presenting symptom.

| 17 |

INN-217: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and The Microbiome

NASH is a growing epidemic affecting approximately 5 – 6% of the general population. An additional 10% to 20% of the general population who ingest little (< 70 g/week for females and <140 g/week for males) to no alcohol are characterized with fat accumulation in the liver, without inflammation or damage, a condition called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The progression of fatty liver to NAFLD to NASH to cirrhosis is a serious condition which has no approved FDA treatment. Evidence supporting a role for the gut-liver axis in the pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH has been accumulating over the past 20 years. LPS or endotoxin translocation is thought to be a primary cause of downstream signaling in the liver causing inflammation and damage. NASH is associated with increased gut permeability caused by disruption of intercellular tight junctions in the intestine allowing LPS from bacteria to pass into the portal circulation to the liver directly damaging hepatocytes. LPS constitutes the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of most gram-negative bacteria. LPS is comprised of a hydrophilic polysaccharide and a hydrophobic component known as lipid A which is responsible for the major bioactivity of endotoxin. When released and translocated into the bloodstream from the gut, LPS can cause a variety of cytokine activity and inflammation in the host.

The disrupted barrier along with an altered microbiome in the gut contribute to NASH as recently demonstrated by a group from Emory University, Rahman et. al. , in Gastroenterology (2016). Knockout mice missing the junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A) ( F11r-/- ), which have a defect in the intestinal epithelial barrier thus making it “leaky,” develop more severe steatohepatitis. JAM-A is a component of the tight junction complex that regulates intestinal epithelial paracellular permeability. F11r-/- mice therefore have leaky tight junctions that allow for translocation of gut bacteria to peripheral organs. By restoring the leaky tight junctions, larazotide could potentially have a beneficial therapeutic effect by blocking translocation of bacterial toxins via the paracellular pathway and may also help normalize the dysbiotic microbiome found in NASH.

According to a marketing and research firm, GlobalData, the market for NASH therapeutics is expected to grow significantly. GlobalData estimates that the market in the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Japan for such therapeutics will be approximately $25.3 billion by 2026. We expect that this market could be addressed by larazotide, although we are unable to estimate what portion until the effect in this population has been studied in clinical trials to understand the specific patient-type in NASH that may derive benefit.

Figure 12: Growing NASH population up to 5%-6% of adults in the US alone.

INN-289: Crohn’s Disease: Chronic Disease with need to oral therapeutics

Innovate is working on a proprietary formulation of larazotide for Crohn’s disease, INN-289. Animal data has shown the effect of larazotide on disease attenuation in an IL-10 knockout mouse model (Arrieta, 2009), which has been well established and used for several drug development programs. Larazotide was placed in the drinking water of the mice at a low dose (0.1 mg/ml) or high dose (1.0 mg/ml) during the period from 4 to 17 weeks of age. Results were compared to wild type mice, IL-10 knockout mice with no treatment, and IL-10 knockout mice treated with probiotics. Intestinal and colonic permeability was significantly reduced in the high dose larazotide treatment group, but not in the untreated IL-10 knockout group. Larazotide treatment caused a reduction in all tissue markers of colonic inflammation (IFNγ and TNFα) and in histological inflammation.

| 18 |

Other Indications using Larazotide’s Mechanism of Action

Larazotide for Environmental Enteric Dysfunction (EED): Positive in vitro Data;

Environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) is a rare pediatric tropical disease in the U.S. and Europe, however, more than 165 million children in developing countries in Africa and Asia suffer from it. As per section 524 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C) Act, EED would likely fall under ’‘Current List of Tropical Disease’’ number ’S,’ thus making a drug approved for EED in the U.S. potentially eligible for a Priority Review Voucher.

The histological presentation of EED is very similar to celiac disease with villous atrophy and chronic inflammation of the small bowel and the pathogenesis of EED is linked to increased intestinal permeability. We have tested larazotide against some of the pathogens commonly found in EED (unpublished) and found positive in vitro results which will need to be confirmed in animal models before starting a clinical trial in EED.

INN-108: Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis

INN-108 is in development for mild-to-moderate UC and is expected to enter a proof-of-concept Phase 2 trial in the second half of 2018 after a successful Phase 1 trial at currently approved doses of mesalamine. UC is an IBD that affects more than 1.25 million people in the major markets of the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Japan and is characterized by inflammation and ulcers in the colon and rectum. UC is a chronic disease that can be debilitating and sometimes lead to life-threatening complications. While poorly understood, a multitude of environmental factors and genetic vulnerabilities are thought to lead to the dysregulation of the immune response via a defective epithelial barrier. Although the majority of patients present with mild-to-moderate UC which can progress to severe UC, the focus of drug development has been in moderate-to-severe UC with little innovation or drug development for mild-to-moderate UC. The mainstay of treatment for mild-to-moderate UC remain various oral reformulations of mesalamine or 5-ASA (5-amino salicylic acid) such as Shire’s Lialda (approved 2007) and Pentasa (approved 1993), Allergan’s Asacol HD (approved 2008) and Valeant/Salix’s Apriso (approved 2008).

The initial IND was filed with the FDA by Nobex Corporation on May 15, 2003 for the use of APAZA (INN-108) for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. The IND was then transferred from Seachaid Corporation to Innovate effective March 19, 2014. Two Phase 1 studies in healthy subjects and patients with ulcerative colitis were conducted by Nobex with INN-108. No serious adverse events were reported during either study.

INN-108 uses an azo-bonded pro-drug approach linking mesalamine to 4-APAA. Mitsubishi Pharma developed 4-APAA as Actarit in Japan which was approved in 1994 for rheumatoid arthritis. IBD drugs were all originally approved for RA, from the oldest 5-ASA, sulfasalazine, to the latest biologics, Humira and Enbrel. 4-APAA has more than two decades of safety data as a standalone drug and has an MoA which is differentiated from mesalamine though the ultimate effect for both is anti-inflammatory (Figure 13). Taken orally as a tablet, the azo-bond protects INN-108 from the low pH in the stomach, thus allowing it to transit to the colon where the UC lesions are located. In the colon, the azo bond is broken enzymatically leading to the release of mesalamine and 4-APAA which have a synergistic anti-inflammatory effect. With the addition of 4-APAA, which is not approved in the U.S. or EU, to the already approved mesalamine, the synergistic effect could lead to superior clinical efficacy over the currently approved oral mesalamines.

Figure 13: 4-APAA is covalently bonded to 5-ASA via a high energy azo-bond which is only enzymatically cleaved in the colon. The anti-inflammatory effect of each of 5-ASA and 4-APAA via different pathways which could lead to a potential synergistic anti-inflammatory effect as seen in animal studies.

| 19 |

INN-108: UC Animal Model Data Shows Synergy between 4-APAA and Mesalamine

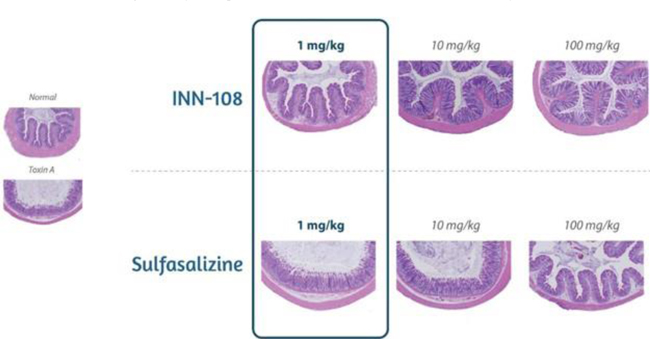

The effects of chronic treatment with INN-108 on Clostridium diffıcile toxin A — induced colitis of the colon is shown in Figure 14. Orally administered INN-108 was significantly more potent than sulfasalazine or 4-APAA alone (McVey, 2005).

Figure 14: A rat UC model using toxin A induced-colitis as the insult leads to sloughing of the colonic epithelium with increasing doses. Using sulfasalazine vs. INN-108 to protect against the toxin A injury showed INN-108 was significantly more potent that sulfasalazine. Source: McVey DC et al. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2005 Mar 1;50(3):565-73.

INN-108 Clinical Development Pathway

After completing two Phase 1 studies, the first of which was conducted between June 2003 and July 2003, and the second of which was conducted between and February 2004 and June 2004, a profile was established with dosing of mesalamine and 4-APAA at 2 grams each for a total of 4 grams three times a day.

The typical dose of the various approved mesalamine formulations range from 1.5g to 2.4g per day, thus INN-108’s mesalamine content is within the established approved dose range. The addition of 4-APAA is thought to improve the efficacy above mesalamine, which would allow INN-108 to be used either after or instead of current mesalamines. In a Phase 2 trial, we plan to compare INN-108 to mesalamine seeking to demonstrate a greater clinical effect than mesalamine alone.

Ulcerative Colitis: Lack of Innovation in New Drug Development for Past Several Decades

Conventional therapies broadly inhibit mechanisms involved in the inflammatory process and are commonly used to effectively treat patients experiencing a mild-to-moderate form of the disease. For mild-to-moderate UC, oral mesalamine has an established efficacy and safety profile. However, gastroenterologists cite the need for new therapies for mild-to-moderate UC.

Patients who do not respond to mesalamine are typically eventually transitioned to biologics. The primary targets for biologics have been to control the immune response and inflammatory cascade, by inhibiting or downregulating molecules such as TNF-α, NF-κB, IL-1β and IFN1-γ. We believe INN-108 bridges the gap between mesalamine and biologics by its mechanism of action of both inhibiting the inflammatory process and down-regulating the cytokines.

About Ulcerative Colitis

UC is a chronic intermittent relapsing inflammatory disorder of the large intestine and rectum. While poorly understood, a multitude of environmental factors and genetic vulnerabilities are thought to lead to the dysregulation of the immune response via a defective epithelial barrier. As a result, chronic inflammation and ulceration of the colon occurs. UC is specific to the colon and affects only the mucosal lining of the colon. Common symptoms of UC include diarrhea, bloody stools, and abdominal pain. The majority of patients are intermittent in their disease course, in that they experience a relapse among periods of remission. However, some patients experience only a single episode of the disease prior to maintaining remission whereas other patients are chronically symptomatic and may require a proctocolectomy to treat their condition.

| 20 |

History of Drug Development in Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis

The original compound used in UC was sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), a conjugate of 5-ASA linked to sulfapyridine by an azo bond, which is split into the two molecules by bacterial azoreductases in the colon. The 5-ASA component or mesalamine is the active therapeutic moiety of sulfasalazine, with sulfapyridine thought to have little if any therapeutic effect. Sulfapyridine, however, is the cause of most of the significant adverse side effects of sulfasalazine.

This led to the development of other 5-ASA preparations utilizing azo chemistry to deliver high concentrations of mesalamine or 5-ASA to the colon by preventing early absorption of the drug in the small intestine. Such preparations include olsalazine (Dipentum), consisting of two molecules of 5-ASA bonded together by an azo bond, and balsalazide (Colazal), consisting of 5-ASA azo bonded to an inert carrier (4-aminobenzoyl-β-alanine). The efficacy of these newer oral forms of 5-ASA is comparable to that of sulfasalazine, but they are better tolerated. However, some side effects persist which prevent wider use. In each of these preparations, the only active moiety is mesalamine or 5-ASA, an anti-inflammatory agent.

INN-329

INN-329 is a proprietary formulation of secretin, a peptide hormone which is used to improve visualization in a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) procedures. Secretin is a 27-amino acid long hormone which rapidly stimulates release of pancreatic secretions, thus improving visualization of the pancreatic ducts during imaging procedures. Secretin has also been tested in a variety of central nervous system conditions such as autism, though currently approved only for pancreatic function testing and imaging with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).. We acquired the assets of secretin from Repligen Corporation in December 2014.

The initial IND and was filed with the FDA by Repligen on July 29, 2005 for MRCP. The IND was transferred from Repligen to Innovate in January 2015. The New Drug Application (NDA) for MRCP was filed with the FDA on December 21, 2011 and was transferred to Innovate in January 2015.

MRCP has been used for more than 20 years as a non-invasive tool for imaging pancreatic ducts. With the addition of secretin pancreatic secretions are increased leading to significantly improved visualization of the pancreatic ducts for detection of abnormalities, including pancreatic cancer. The gold standard for pancreatic duct imaging had been ERCP, an expensive and invasive procedure with complications such as pancreatitis (3 − 5%), bleeding (1 − 2%), perforation (1%), infection (1 − 2%) and death (1/250). More than a half-million ERCP procedures are performed annually in the U.S. and as the role of ERCP diminishes for screening, it will further the need for approval of secretin for S-MRCP. We expect to repeat a Phase 3 trial with a partner, if and when secured, as per previous discussion with the FDA to look at improvement in visualization of the pancreatic duct via MRCP with and without secretin.

Our Intellectual Property

We strive to protect the proprietary technology that we believe is important to our business, including our product candidates and our processes. We seek patent protection in the United States and internationally for our product candidates, their methods of use, and processes of manufacture and any other technology to which we have rights, as appropriate. Additionally, we have licensed the rights to intellectual property related to certain of our product candidates, including patents and patent applications that cover the products or their methods of use or processes of manufacture. The terms of the licenses are described below under the heading “Licensing Agreements.” The patent families related to the intellectual property covered by the licenses include 29 U.S. patents and 107 foreign patents with expiration dates ranging from 2018 to 2035. We also rely on trade secrets that may be important to the development of our business.

Our success will in part depend on the ability to obtain and maintain patent and other proprietary rights in commercially important technology, inventions and know-how related to our business, the validity and enforceability of our patents, the continued confidentiality of our trade secrets, and our ability to operate without infringing the valid and enforceable patents and proprietary rights of third parties. We also rely on continuing technological innovation and in-licensing opportunities to develop and maintain our proprietary position.

We cannot be sure that patents will be granted with respect to any of our pending patent applications or with respect to any patent applications we may own or license in the future, nor can we be sure that any of our existing patents or any patents we may own or license in the future will be useful in protecting our technology and products. For this and more comprehensive risks related to our intellectual property, please see “Risk Factors—Risks Related to Our Intellectual Property.”

| 21 |

CeD PRO: Copyrighted Primary Endpoint for Celiac Disease Tested in a Successful Clinical Trial

The patient reported outcome (PRO) primary end point for celiac disease (CeD PRO) was developed based on FDA guidance and is copyrighted in the United States effective October 13, 2011. The copyright registration is in effect for 95 years from the year of first publication or 120 years from the year of creation, whichever expires first. If the drug is approved by the FDA and is the first drug to be approved for celiac disease, Innovate believes that the PRO will become the standard for assessing efficacy in celiac disease. Competitor companies seeking to use a PRO to establish efficacy in this indication would either need to develop their own PRO or would be required to license the CeD PRO from Innovate, thus providing an additional barrier to competitor entry into the marketplace.

Strategic Collaborations and License Agreements

We have entered into collaboration agreements with several academic institutions and other contract research organizations to investigate pre-clinical studies for the use of our product candidates in potential other indications or to further broaden our understanding of the current indications.

Licensing Agreements

License with Alba Therapeutics Corporation

In February 2016, we entered into a license agreement (the “Alba License”) with Alba Therapeutics Corporation (“Alba”) to obtain an exclusive worldwide license to certain intellectual property relating to larazotide and related compounds.

Our initial area of focus for this asset relates to the treatment of celiac disease. We now refer to this program as INN-202. The license agreement gives us the rights to (i) patent families owned by University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) and licensed to Alba, (ii) certain patent families owned by Alba, and (iii) one patent family that is jointly owned. In connection with the Alba License, we also entered into a sublicense agreement with Alba under which Alba sublicensed the UMB patents to us (the “Alba Sublicense”).

As consideration for the Alba License, we agreed to pay (i) a one-time, non-refundable fee of $0.4 million at the time of execution and (ii) set payments totaling up to $151.5 million upon the achievement of certain milestones in connection with the development of the product, which milestones include the dosing of the first patient in the Phase 3 clinical trial, acceptance and approval of the New Drug Application, the first commercial sale, and the achievement of certain net sales targets. The last milestone payment is due upon the achievement of annual net sales of INN-202 in excess of $1.5 billion. Upon the first commercial sale of INN-202, the license becomes perpetual and irrevocable. The term of the Alba Sublicense, for which we paid a one-time, non-refundable fee of $0.1 million, extends until the earlier of (i) the termination of the Alba License, (ii) the termination of the underlying license agreement, or (iii) an assignment of the underlying license agreement to us. After we make the first milestone payment after the dosing of the first patient in the Phase 3 clinical trial and are able to demonstrate sufficient financial resources to complete the trial, we have the exclusive option to purchase the assets covered by the license.

The patents covering the composition-of-matter for the larazotide peptide expire in 2018 (2019 outside the United States). The Alba Therapeutics patent estate nevertheless provides product exclusivity for INN-202 in the U.S. until June 4, 2031, not including patent term extensions that may apply upon product approval.

Significant patents in the INN-202 patent estate include issued patents in the U.S. for methods of treating celiac disease with larazotide (US Patents 8,034,776 and 9,279,807), of which the last to expire has a term to July 16, 2030.

Other significant patents include the larazotide formulation patent family, which has three issued U.S. patents as well as 39 filings outside the U.S. (31 issued). The significant patents in the INN-202 patent estate formulation patent family includes patents covering the composition-of-matter (US Patent 9,265,811) and corresponding methods of treatment (US Patents 8,168,594 and 9,241,969) for the larazotide formulation, with the last to expire patent having an expiration in the U.S. of June 4, 2031.

| 22 |

License with Seachaid Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

In April 2013, we entered into a license agreement (the “Seachaid License”) with Seachaid Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (“Seachaid”) to further develop and commercialize the licensed product, the compound known as APAZA. This program is now referred to as INN-108 by us.

The license agreement gives us the exclusive rights to (i) commercialize products covered by the patents owned or controlled by Seachaid related to the composition, formulation or use of any APAZA compound in the territory that includes the U.S., Canada, Japan, and most countries in Europe, and (ii) use, research, develop, export and make products worldwide for the purposes of such commercialization.

As consideration for the Seachaid License, we agreed to pay a one-time, non-refundable fee of $0.2 million at the earlier of the time we meet certain financing levels or 18 months following the execution of the agreement and set payments totaling up to $6.0 million upon the achievement of certain milestones in connection with the development of the product, filing of the New Drug Application, the first commercial sale, and payments ranging from $1.0 million to $2.5 million based on the achievement of certain net sales targets. There are future royalty payments in the single digits based on achieving sales targets, and we are required to pay Seachaid a portion of any sublicense revenue. The royalty payments continue for each licensed product and in each applicable country until the earlier of (i) the date of expiration of the last valid claim for such products to expire or (ii) the date that one or more generic equivalents if such product makes up 50 percent or more of sales in the applicable country. The term of the Seachaid License extends on a product-by-product and country-by-country basis until the expiration of the royalty period for the applicable product in the applicable country.

The INN-108 patent estate includes issued patents for:

(i.) immunoregulatory compounds and derivatives and methods of treating diseases therewith, of which the last to expire has a term to December 17, 2021 (in the U.S.) and August 28, 2021 (in Europe);

(ii.) methods and compositions employing 4-aminophenylacetic acid, of which the last to expire has a term to to August 29, 2021 (in the U.S.);

(iii.) 5-ASA derivatives having anti-inflammatory and antibiotic activity, of which the last to expire has a term to August 29, 2021 (in the U.S.) and August 28, 2021 (in Europe); and

(iv.) synthesis of azo bonded immunoregulatory compounds, of which the last to expire has a term to May 31, 2028 (in the U.S.) and July 7, 2025 (in Europe).

The corresponding European patent application for (ii.) methods and compositions employing 4-aminophenylacetic acid is still pending, but if issued would provide a term to March 22, 2025 in the countries where the application is validated.

The INN-108 patent estate includes also provisional patent applications for pharmaceutical compositions, delivery compositions, methods of prophylaxis and methods of treatment. These patent applications have not yet been issued, and so it is impossible to know the expiration date of any intellectual property that might result from these applications.

| 23 |

Asset Purchase Agreement

In December 2014, we entered into an Asset Purchase Agreement (the “Asset Purchase Agreement”) with Repligen Corporation (“Repligen”) to acquire Repligen’s RG-1068 program for the development of secretin for the pancreatic imaging market and MRCP procedures. We now refer to this program as INN-329. As consideration for the Asset Purchase Agreement, we agreed to make a non-refundable cash payment on the date of the agreement and future royalty payments consisting of a percentage between five and fifteen of annual net sales, with such royalty payment percentage increasing as annual net sales increase. The royalty payments are made on a product-by-product and country-by-country basis and the obligation to make the payments expires with respect to each country upon the later of (i) the expiration of regulatory exclusivity for the product in that country or (ii) ten years after the first commercial sale in that country. The royalty amount is subject to reduction in certain situations, such as the entry of generic competition in the market.

Manufacturing and Supply

We contract with third parties for the manufacturing of all of our product candidates, including INN-108, INN-202 and INN-329, for pre-clinical and clinical studies and intend to continue to do so in the future. We do not own or operate any manufacturing facilities, and we have no plans to build any owned clinical or commercial scale manufacturing capabilities. We believe that the use of contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) eliminates the need to directly invest in manufacturing facilities, equipment and additional staff. Although we rely on contract manufacturers, our personnel or consultants have extensive manufacturing experience overseeing CMOs.

As we further develop our molecules, we expect to consider secondary or back-up manufacturers for both active pharmaceutical ingredient and drug product manufacturing. To date, our third-party manufacturers have met the manufacturing requirements for our product candidates in a timely manner. We expect third-party manufacturers to be capable of providing sufficient quantities of our product candidates to meet anticipated full-scale commercial demands but we have not assessed these capabilities beyond the supply of clinical materials to date. We currently engage CMOs on a ’‘fee for services’’ basis based on our current development plans. We plan to identify CMOs and enter into longer term contracts or commitments as we move our product candidates into Phase 3 clinical trials.

We believe alternate sources of manufacturing will be available to satisfy our clinical and future commercial requirements; however we cannot guarantee that identifying and establishing alternative relationships with such sources will be successful, cost effective, or completed on a timely basis without significant delay in the development or commercialization of our product candidates. All of the vendors we use are required to conduct their operations under current Good Manufacturing Practices, or cGMP, a regulatory standard for the manufacture of pharmaceuticals.

Commercialization

We own or control exclusive rights to all three of our product candidates in the markets of the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Japan. We plan to pursue regulatory approvals for our products in the United States and the European Union, and may independently commercialize these products in the United States. In doing so, we may engage strategic partners to assist with the sales and promotion of our products.

Our anticipated commercialization strategy in the United States would target key prescribing physicians, including specialists such as gastroenterologists, as well as provide patients with support programs to ensure product access. Outside of the United States, we plan to seek partners to commercialize our products via out-licensing agreements or other similar commercial arrangements.

| 24 |

Competition

The pharmaceutical industry is highly competitive and characterized by intense and rapidly changing competition to develop new technologies and proprietary products. Our potential competitors include both major and specialty pharmaceutical companies worldwide. Our success will be based in part on our ability to identify, develop and manage a portfolio of product candidates that are safer and more effective than competing products.

The competitive landscape in celiac disease is currently limited, which we believe is due to lack of significant past R&D investments and lack of recognition and education around the disease. To our knowledge, there are no late stage competitors entering Phase 3 clinical trials or any who have successfully completed Phase 2 studies to date. However, in recent years large pharmaceutical companies have begun to expand their focus areas to autoimmune diseases such as celiac disease, and given the unmet medical needs in these areas, we anticipate increasing competition. A few early stage programs are active, with time to enter Phase 1 clinical trials still several years away, including Roche/Genetech’s RG7625 (cathepsin S inhibitor), Takeda/PvP’s KumaMax (gluten degrading enzyme), Celimmune/Amgen’s AMG-714 (an IL-15 MAb) and Dr. Falk Pharma/Zeria’s ZED-1227 (a tTG-2 inhibitor). ImmunogenX’s IMGX003 (two gluten degrading enzymes) failed to meet its primary endpoint in a Phase 2b trial in 2015.

| Product | Status | Mechanism | Company | Route | Product Type | |||||

| AMG 714 | Phase 2 |

Anti-IL-15 MAb |

Celimmune/ Amgen |

Subcutaneous; 2x/month |

MAb (humanized) | |||||

| ZED-1227 | Phase 1b | TGase-2 inhibitor |