Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| EX-32.1 - EX-32.1 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex321f09cfd.htm |

| EX-31.2 - EX-31.2 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex312588702.htm |

| EX-31.1 - EX-31.1 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex311ac2ffb.htm |

| EX-23.2 - EX-23.2 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex23261a275.htm |

| EX-23.1 - EX-23.1 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex231344fb3.htm |

| EX-21.1 - EX-21.1 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex2117547aa.htm |

| EX-10.8.1 - EX-10.8.1 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex1081dd2cc.htm |

| EX-10.26 - EX-10.26 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex10263522f.htm |

| EX-10.25 - EX-10.25 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex102551729.htm |

| EX-10.24 - EX-10.24 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex102402d11.htm |

| EX-10.23 - EX-10.23 - AveXis, Inc. | avxs-20171231ex102393f8e.htm |

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 10-K

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF

THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

|

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017 |

Commission file number 001-37693 |

AVEXIS, INC.

|

State of Delaware |

90-1038273 |

|

Incorporated under the Laws of the |

I.R.S. Employer Identification No. |

2275 Half Day Rd, Suite 200

Bannockburn, Illinois 60015

(847) 572-8280

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Exchange Act:

|

Title of each class |

Name of each exchange on which registered |

|

|

Common Stock, $0.0001, par value |

|

The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Exchange Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulations S-K (§ 229.405 of this chapter) is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant's knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

|

Large accelerated filer ☒ |

Accelerated filer ☐ |

Non-accelerated filer ☐ |

Smaller reporting company ☐ |

|

|

|

(Do not check if a |

Emerging growth company ☐ |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ☐ No ☒

The aggregate market value of the voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates of the registrant based on the closing price of the registrant’s common stock for the last business day of the registrant’s most recently completed second fiscal quarter: $2,265,553,538

As of February 26, 2018, 36,725,399 shares of common stock, $0.0001 par value, were outstanding.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Part III of this Annual Report on Form 10-K incorporates by reference information (to the extent specific sections are referred to herein) from the registrant’s Proxy Statement for its 2018 Annual Meeting of Stockholders.

SPECIAL NOTE REGARDING FORWARD‑LOOKING STATEMENTS

This Annual Report on Form 10‑K (this “Annual Report”) contains forward‑looking statements, within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, that involve substantial risks and uncertainties. The forward‑looking statements are contained principally in Part I, Item 1: “Business,” Part I, Item 1A: “Risk Factors,” and Part 2, Item 7: “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations,” but are also contained elsewhere in this Annual Report. In some cases, you can identify forward‑looking statements by terms such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “plan,” “anticipate,” “could,” “intend,” “target,” “project,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “potential” or “continue” or the negative of these terms or other similar expressions intended to identify statements about the future. These statements speak only as of the date of this Annual Report and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other important factors that may cause our actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by the forward‑looking statements. We have based these forward‑looking statements largely on our current expectations and projections about future events and financial trends that we believe may affect our business, financial condition and results of operations. These forward‑looking statements include, without limitation, statements about the following:

|

· |

the timing, progress and results of preclinical studies and clinical trials for AVXS‑101 and any other product candidates, including statements regarding the timing of initiation and completion of studies or trials and related preparatory work, the period during which the results of the trials will become available and our research and development programs; |

|

· |

the timing of and our ability to obtain and maintain regulatory approval of AVXS‑101; |

|

· |

the proposed clinical development pathway for AVXS‑101, including the expected trial design for our current and proposed pivotal clinical trials, and the acceptability of the results of such trials for regulatory approval of AVXS‑101 by the FDA or comparable foreign regulatory authorities; |

|

· |

the proposed timing of filing investigational new drug applications with the FDA in connection with gene therapies we are developing for Rett syndrome and a genetic form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by mutations in the superoxide dismutase 1 gene; |

|

· |

our expectations regarding timing for meetings with regulatory agencies; |

|

· |

our expectations regarding the size of the patient populations for our product candidates, if approved for commercial use; |

|

· |

our manufacturing capabilities and strategy, including the scalability and commercial viability of our manufacturing methods and processes; |

|

· |

our ability to successfully commercialize AVXS‑101; |

|

· |

our estimates of our expenses, ongoing losses, future revenue, capital requirements and our needs for or ability to obtain additional financing; |

|

· |

our ability to identify, license and develop new product candidates; |

|

· |

our ability to identify, recruit and retain key personnel; |

|

· |

our and our licensors’ ability to protect and enforce our intellectual property protection for AVXS‑101, and the scope of such protection; |

|

· |

our financial performance; |

|

· |

the development of and projections relating to our competitors or our industry; |

|

· |

our expectations about the outcome of litigation and controversies with third parties, including the lawsuit filed by Sophia’s Cure Foundation; and |

|

· |

the impact of laws and regulations, including, without limitation, recently enacted tax reform legislation. |

You should refer to “Item 1A. Risk Factors” in this Annual Report for a discussion of important factors that may cause our actual results to differ materially from those expressed or implied by our forward‑looking statements. As a result of these factors, we cannot assure you that the forward‑looking statements in this Annual Report will prove to be accurate. Furthermore, if our forward‑looking statements prove to be inaccurate, the inaccuracy may be material. In light of the significant uncertainties in these forward‑looking statements, you should not regard these statements as a representation or warranty by us or any other person that we will achieve our objectives and plans in any specified time frame, or at all. The forward‑looking statements in this Annual Report represent our views as of the date of this Annual Report. We anticipate that subsequent events and developments may cause our views to change. However, while we may elect to update these forward‑looking statements at some point in the future, we undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward‑looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except as required by law. You should, therefore, not rely on these forward‑looking statements as representing our views as of any date subsequent to the date of this Annual Report.

You should read this Annual Report on Form 10‑K and the documents that we reference in this Annual Report on Form 10‑K and have filed as exhibits to this Annual Report on Form 10‑K completely and with the understanding that our actual future results may be materially different from what we expect. We qualify all of our forward‑looking statements by these cautionary statements.

Overview

We are a clinical‑stage gene therapy company dedicated to developing and commercializing novel treatments for patients suffering from rare and life‑threatening neurological genetic diseases. Our initial product candidate, AVXS‑101, is our proprietary gene therapy product candidate for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA. SMA is a severe neuromuscular disease characterized by the loss of motor neurons, leading to progressive muscle weakness and paralysis. The incidence of SMA is approximately one in 10,000 live births. SMA is generally divided into sub‑categories termed SMA Type 1, 2, 3 and 4. We are conducting a pivotal clinical trial for AVXS‑101 for the treatment of SMA Type 1, the leading genetic cause of infant mortality. SMA Type 1 is a lethal genetic disorder characterized by motor neuron loss and associated muscle deterioration, resulting in mortality or the need for permanent ventilation support before the age of two for greater than 90% of patients. In the incident population, approximately 60% of SMA patients have Type 1. In our recently completed Phase 1 clinical trial of AVXS‑101 in patients with SMA Type 1, we observed a favorable safety profile, and that AVXS-101 was generally well-tolerated. As of August 7, 2017, all patients in the trial survived event-free at 20 months of age, in contrast to the 8% event-free rate at 20 months demonstrated in an independent, peer-reviewed natural history study of patients with SMA Type 1. Additionally, we observed improved motor function and the attainment of motor milestones such as the ability to sit unassisted in the majority of patients, and in some patients, the ability to crawl, stand and walk — motor milestone achievements that are essentially never seen among untreated patients suffering from SMA Type 1.

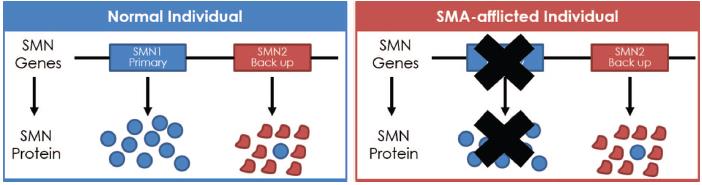

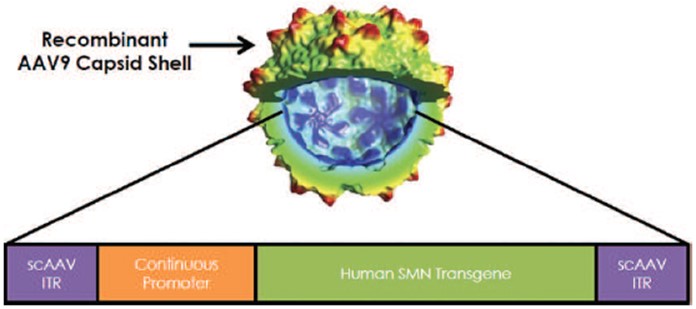

The survival motor neuron protein, or SMN, is a critical protein for normal motor neuron signaling and function. SMA, and the SMA sub‑types, are diagnosed by identifying the existence of a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene, by determining the number of copies of the SMN2 backup gene, which correlates with disease onset and severity and clinical signs and symptoms of the disease. Patients with SMA Type 1 either have experienced a deletion of their SMN1 genes, which prevents them from producing adequate levels of functional SMN protein, or carry a mutation in their SMN1 gene. AVXS‑101 is designed to deliver a fully functional human SMN gene into the nuclei of target cells, including motor neurons that then generates an increase in SMN protein levels, and we believe this will result in improved motor neuron function and patient outcomes. We believe gene therapy is a therapeutic approach that is well‑suited for the treatment of SMA due to the monogenic nature of the disease, meaning it is caused by mutations in or deletions of a single gene. AVXS‑101 is designed to possess the key elements of an optimal gene therapy approach to SMA, potentially enabling a one‑time dose regimen: delivery of a fully functional human SMN gene into target motor neuron cells; production of sufficient levels of SMN protein required to improve motor neuron function; and rapid onset of effect in addition to sustained SMN gene expression. AVXS‑101 utilizes a non‑integrating adeno‑associated virus, or AAV, capsid to deliver a functional copy of a human SMN gene to the patient’s own cells without modifying the existing DNA of the patient. Unlike many other capsids, the AAV9 capsid utilized in AVXS‑101 crosses the blood‑brain barrier, a tight protective barrier which regulates the passage of substances between the bloodstream and the brain, thus allowing for intravenous administration. In addition, AAV9 has been observed in preclinical studies to efficiently target motor neuron cells when delivered via either intrathecal or intravenous administration. AVXS‑101 has a self‑complementary DNA sequence that enables rapid onset of effect and a continuous promoter that is intended to allow for continuous and sustained SMN gene expression. Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, approved an alternative-splicing drug for the treatment of SMA in December 2016, we believe that there remains significant unmet medical need and interest in a gene replacement therapy for SMA that can act on the underlying defect in the SMN1 gene and that can provide enhanced survival and motor function benefit via a one‑time dose.

The FDA and the European Medicines Agency, or EMA, have each granted AVXS-101 orphan drug designation for the treatment of SMA, and the FDA has granted AVXS-101 fast track designation for the treatment of SMA Type 1. The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation for AVXS-101 for the treatment of SMA Type 1 in pediatric patients. The FDA established breakthrough therapy designation to facilitate dialogue between the FDA and the sponsor to provide advice on generating evidence needed to support approval of the therapy in an efficient manner with more intensive and interactive guidance on an efficient drug development program, an organizational commitment involving the FDA’s senior managers, and eligibility for rolling review and priority review. We intend to request a pre-

1

Biologics License Application, or BLA, meeting for AVXS-101 in SMA with the FDA in the second quarter of 2018. The EMA granted access into its PRIority MEdicines, or PRIME, program for AVXS-101 for the treatment of SMA Type 1. PRIME is intended to enhance support for the development of medicines—specifically those that may offer a major therapeutic advantage over existing treatments or benefit patients without treatment options—through early and proactive support by EMA to optimize the generation of robust data and development plans, and potentially expedite the assessment of the marketing authorization application so these medicines may reach patients sooner. In addition, we intend to seek EMA Pre-Submission Scientific Advice in the first half of 2018 to determine if the data from our Phase 1 study of AVXS‑101 may meet the evidentiary requirements for the conditional approval pathway in the European Union.

We are also currently conducting a Phase 1 clinical trial of AVXS-101 for the treatment of SMA Type 2. SMA Type 2 typically presents between six and 18 months of age, and those affected will never walk without support and most will never stand without support. SMA Type 2 results in mortality in more than 30% of patients by the age of 25. In addition to our ongoing clinical trials, we intend to expand our clinical development program of AVXS-101 for the treatment of SMA by initiating three additional clinical trials to further evaluate AVXS-101, including in new patient populations. First, we intend to initiate a pivotal trial of AVXS-101 for the treatment of SMA Type 1 in Europe during the first half of 2018. Second, we intend to initiate a trial for pre-symptomatic SMA patients with two, three and four copies of the SMN2 backup gene, who are less than six weeks of age at the time of gene therapy, to evaluate appropriate clinical endpoints of a one-time intravenous, or IV, dose of AVXS-101 in the first half of 2018. Finally, we intend to initiate a pediatric "all comers" trial for approximately 50 patients between approximately six months and 18 years of age who do not qualify for other AVXS-101 trials at the time of gene therapy, to evaluate a one-time intrathecal, or IT, dose of AVXS-101 in the late fourth quarter of 2018 or early 2019.

We have an exclusive, worldwide license with Nationwide Children’s Hospital, or NCH, under certain patent applications related to both the intravenous and intrathecal delivery of AVXS‑101 for the treatment of all types of SMA, and an exclusive, worldwide license, with rights to sublicense, from REGENXBIO Inc., or REGENXBIO, to any recombinant AAV vector in REGENXBIO’s intellectual property portfolio for the in vivo gene therapy treatment of SMA in humans. In addition, we have a non‑exclusive, worldwide license agreement with Asklepios BioPharmaceutical Inc., or AskBio, under certain patents and patent applications owned by the University of North Carolina and licensed to AskBio for the use of its self‑complementary DNA technology for the treatment of SMA.

In 2013, in connection with the exclusive license agreement with NCH, we formed a collaboration with NCH to explore the use of gene therapy for the treatment of SMA and secured our first institutional investors and expanded our leadership team. Our current operations are a result of this collaboration with NCH and research conducted by our Chief Scientific Officer, Brian Kaspar, Ph.D. Dr. Kaspar has over 20 years of gene therapy experience, and until September 2016 served as a principal investigator in the Center for Gene Therapy at The Research Institute at NCH. NCH is a leading pediatric gene therapy research institute.

In addition to developing AVXS-101 to treat SMA, we plan to develop other novel treatments for two additional rare neurological monogenetic diseases, Rett syndrome and a genetic form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by mutations in the superoxide dismutase 1 gene, or genetic ALS.

To execute on our mission, we have assembled a management team that includes individuals with expertise in gene therapy, regulatory development, product and clinical development, manufacturing, medical affairs and commercialization, with a history of success in building and operating innovative biotechnology and healthcare companies focused on rare and life‑threatening diseases. This team is led by our President and Chief Executive Officer, Sean P. Nolan, who brings over 26 years of broad leadership and management experience in the biopharmaceutical industry to AveXis. Prior to AveXis, Mr. Nolan was the chief business officer of InterMune, Inc. where he led multiple functions across the organization, including North American commercial operations, global marketing, corporate and business development, and global manufacturing and supply chain. Our other management team members also have successful track records developing and commercializing drugs through previous experiences at companies such as Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Centocor, InterMune, Hospira, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo and Quest Diagnostics.

2

Our Strategy

We are building a patient‑centric business with the goal of developing innovative gene therapy treatments that transform the lives of patients and their families suffering from rare and life‑threatening neurological genetic diseases. In order to accomplish this goal, we plan to execute on the following key strategies:

|

· |

Rapidly advance our SMA Type 1 program through clinical trials in the United States. We are conducting a pivotal trial of AVXS-101 in SMA Type 1 using the IV formulation produced by our good manufacturing practice, or GMP, commercial manufacturing process. Five patients have been dosed in this clinical trial to date. In January 2017, we announced the completion of our Phase 1 clinical trial of AVXS‑101 in patients with SMA Type 1, in which we observed a favorable safety profile and that AVXS-101 was generally well-tolerated. As of August 7, 2017, all patients in the trial survived event-free at 20 months of age, in contrast to the 8% event-free rate at 20 months demonstrated in an independent, peer-reviewed natural history study of patients with SMA Type 1. The FDA has granted AVXS‑101 orphan drug designation for the treatment of all types of SMA, fast track designation for the treatment of SMA Type 1 and breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of SMA Type 1 in pediatric patients. We intend to request a pre-BLA meeting for AVXS-101 for SMA Type 1 with the FDA in the second quarter of 2018. |

|

· |

Further expand the development of AVXS‑101 for the treatment of SMA. Based on preclinical data and our preliminary clinical observations to date, we believe AVXS‑101 may also have the ability to treat patients with SMA Types 2, 3 and 4, which result from the same genetic defect as SMA Type 1. We are conducting a Phase 1 safety and dosing escalation study of AVXS‑101 via IT delivery in patients with SMA Type 2. Two patients have been dosed in this clinical trial to date. Furthermore, we intend to initiate a trial for patients with two, three and four copies of the SMN2 backup gene, who are less than six weeks of age and pre-symptomatic at the time of gene therapy, to evaluate appropriate clinical endpoints of a one-time IV dose of AVXS-101 in the first half of 2018. We also intend to initiate a pediatric "all comers" trial for approximately 50 patients between approximately six months and 18 years of age who do not qualify for other AVXS-101 trials at the time of gene therapy, to evaluate a one-time IT dose of AVXS-101 in the late fourth quarter of 2018 or early 2019. |

|

· |

Advance the development of AVXS‑101 outside of the United States. The incidence, standard of care and prognosis of SMA globally are generally consistent. Despite a treatment being approved in Europe during 2017, we believe there is significant unmet need for patients suffering from SMA outside the United States. In January 2017, we announced that the EMA granted AVXS‑101 access into its PRIME program for the treatment of SMA Type 1. We intend to initiate our European pivotal trial of AVXS‑101 for SMA Type 1 during the first half of 2018. In February 2017, we announced that this pivotal trial will reflect a single‑arm design, using natural history of the disease as a comparator, and will enroll approximately 30 patients with SMA Type 1 who are less than six months of age at the time of gene therapy. |

|

· |

Build a pipeline of gene therapy treatments for other rare and life‑threatening neurological genetic diseases, including Rett syndrome and genetic ALS. In addition to our programs in SMA, we also intend to identify, acquire, develop and commercialize novel product candidates for the treatment of other rare and life‑threatening neurological genetic diseases that we believe can be treated with gene therapy. We intend to employ a targeted approach to acquisition and licensing transactions reflecting our goal to be a leading gene therapy company focused on the treatment of rare and life‑threatening neurological diseases. In June 2017, we announced that we had entered into an exclusive, worldwide license agreement with REGENXBIO for the development and commercialization of gene therapy using the recombinant AAV9 vector to treat Rett syndrome and genetic ALS. We expect to move forward with initiating investigational new drug application, or IND, enabling studies in both Rett syndrome and genetic ALS and submit IND applications for both indications in late 2018 or early 2019. |

|

· |

Continue to invest in and develop robust and sustainable manufacturing processes, as well as multiple supply sources, to ensure the supply of high‑quality products. We have built our own commercial scale |

3

cGMP‑compliant manufacturing facility. Based on data from our intended current cGMP development work and feedback from ongoing discussions with the FDA, including our chemistry, manufacturing and controls, or CMC, meeting with the FDA in May 2017, we made the strategic decision to use our intended cGMP derived product in all current and future studies of AVXS‑101 and for all commercial needs if AVXS-101 receives marketing approval. We are executing on our manufacturing plan to ensure there is sufficient supply to meet our needs for both clinical material and for commercial demand, if AVXS-101 is approved by the FDA. We will continue to evaluate our internal manufacturing capabilities and engage third-party manufacturers, if needed, to support production and provide alternate supply for both AVXS-101 and for our other programs. |

|

· |

Invest in developing and accessing intellectual property to further expand our product portfolio. To date, we have secured our intellectual property position through our agreements with our key collaborators and other third parties. We plan to build upon this intellectual property position through additional patent applications related to AVXS‑101. With respect to future product candidates, we expect to continue to work with REGENXBIO and other creators of next generation vectors to ensure appropriate access to additional therapeutic candidates. |

|

· |

Continue to develop a strong, collaborative network of key stakeholders, including patient advocacy groups, healthcare professionals, key opinion leaders and research institutions, to inform our clinical development and commercialization strategies. We believe that it is imperative to put the patient at the center of our focus, and we intend to continue to work and listen closely to key stakeholders to ensure that we clearly understand their issues, insights and recommendations. The feedback from and collaboration with these groups have and will continue to inform our key strategies to transform the lives of patients and their families suffering from rare and life‑threatening neurological genetic diseases with safe and effective therapies. |

Background on Gene Therapy

Many diseases are driven by genetic mutations in which the mutated genes can affect the production of proteins. Gene therapy attempts to address disease biology by introducing recombinant DNA into a patient’s own cells, commonly in the form of a functional copy of the patient’s defective gene, to address the genetic defect and modulate protein production and cellular function, which provides therapeutic benefit.

Using gene therapy, physicians can introduce or re‑introduce genes that encode for a therapeutic protein. Instead of providing proteins or other therapies externally and dosing them over a long period, we believe gene therapy offers the possibility of dosing a patient once to achieve a long‑term, durable benefit. Gene therapies are typically comprised of three elements: a transgene, a promoter and a delivery mechanism such as our AAV9 capsid. Once the therapeutic gene is transferred to a patient’s cells, we believe the cells may be able to continue to produce the therapeutic protein for years or, potentially, the rest of the patient’s life. As a result, gene therapy has the potential to transform the way these patients are treated by addressing the underlying genetic defect.

Background on Spinal Muscular Atrophy

SMA is a severe neuromuscular disease characterized by the loss of motor neurons leading to progressive muscle weakness and paralysis. The incidence of SMA is approximately one in 10,000 live births, and one in 50 people are carriers of the SMA gene (approximately six million Americans). SMA is generally divided into sub‑categories termed SMA Type 1, 2, 3 and 4. SMA, and the SMA sub‑types, the genetic diagnosis is made by first identifying the existence of a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene and then determining the number of copies of the SMN2 backup gene, which correlates with disease onset and severity. If insufficient protein is expressed, muscles do not develop properly.

4

Patients that have SMA Type 1, the most severe type of SMA, have an onset of symptoms within six months of birth, have difficulty breathing and swallowing and will never develop the strength or muscle control to sit up independently or the ability to crawl or walk. SMA Type 1 patients frequently die in early childhood due to complications related to respiratory failure resulting from motor neuron degeneration. Although SMA Types 2, 3 and 4 are generally less severe than SMA Type 1, they still present patients with significant medical challenges. The standard of care for patients with SMA Type 1 has traditionally been limited to palliative therapies, including life‑long respiratory care, ventilator support, nutritional care, orthopedic care and physical therapy. In December 2016, the FDA approved SPINRAZATM (nusinersen), developed by Biogen and Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for the treatment of SMA. Nusinersen employs an approach for the treatment of SMA called alternative splicing, which seeks to achieve more efficient production of full‑length SMN protein from the SMN2 gene. However, we believe that there is significant interest in a gene replacement therapy for SMA that can act on the underlying defect in the primary gene (SMN1) and can provide enhanced survival and motor function benefit via a one‑time dose.

SMA is caused by a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene that codes SMN, a protein necessary for survival of motor neurons. Although individuals typically receive one copy of the SMN1 gene from each parent, only one properly functioning SMN1 gene is required to generate adequate levels of full‑length SMN protein. SMA results from the patient’s lack of a properly functioning SMN1 gene, either due to mutation or loss of the gene. SMA is a recessive trait, meaning that while both parents of an SMA patient may be healthy, they each carry and pass along to their child DNA that contains either a mutated or missing SMN1 gene which results in the disease manifesting itself in the child.

Human DNA contains a backup to the SMN1 gene, the SMN2 gene. Individuals may carry multiple copies of the SMN2 backup gene within their DNA. However, approximately 90% of SMN protein produced by the SMN2 backup gene is non‑functional, truncated SMN protein missing a polypeptide segment (coded for by exon 7) that is essential to form a functional SMN molecule. The level of functional full‑length SMN protein produced by an SMA patient’s SMN2 genes is generally insufficient to prevent loss of proper motor neuron function. As the SMN2 genes are capable of producing minimal levels of full‑length SMN protein, the number of copies of the SMN2 backup gene serves as a disease modifier, such that the more copies of the SMN2 backup gene there are, the less severe the disease. The following diagram presents the difference between a healthy person and someone afflicted by SMA.

SMA is typically diagnosed based on the onset of clinical symptoms along with a genetic assessment of the absence of SMN1 and the number of copies of SMN2. However, a genetic diagnosis can also be made prenatally either through amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling.

The following table describes the general disease onset, incidence rates, survival and general characteristics for each of the different types of SMA.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Incidence per |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of |

|

|

|

Live Birth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Copies |

|

|

|

among SMA |

|

|

|

|

|

SMA Type |

|

of SMN2 |

|

Onset |

|

Types |

|

Survival |

|

Characteristics |

|

Type 1 (Werdnig-Hoffman Disease) |

|

Two |

|

Before six months |

|

Approximately 60% |

|

Less than 10% event free* by two years of age |

|

Will never be able to sit without support |

|

Type 2 (Dubowitz Syndrome) |

|

Three or Four |

|

6 - 18 months |

|

Approximately 27% |

|

68% alive at age 25 |

|

Will never be able to walk or stand without support |

|

Type 3 (Lugelberg-Welander Disease) |

|

Three or Four |

|

Early childhood to early adulthood (juvenile) |

|

Approximately 13% |

|

Normal |

|

Stand alone and walk but may lose ability to walk in 30s - 40s |

|

Type 4 |

|

Four to Eight |

|

Adulthood (20s - 30s) usually after 30 |

|

Uncommon: limited incidence information available |

|

Normal |

|

Same as Type 3 |

5

|

* |

An event is defined as death or at least 16 hours per day of required ventilation support for breathing for 14 consecutive days in the absence of acute reversible illness or perioperatively. |

SMA Type 1

SMA Type 1 is a lethal genetic disorder characterized by motor neuron loss and associated muscle deterioration, resulting in mortality or the need for permanent ventilation support before the age of two for greater than 90% of patients. SMA Type 1 is the leading genetic cause of infant mortality. SMA Type 1 accounts for approximately 60% of all new SMA cases. Symptoms of SMA Type 1 include:

|

· |

hypotonia, which is also known as “floppy baby syndrome” and is characterized by abnormal limpness in the neck and limbs; |

|

· |

muscle weakness, particularly in the legs; |

|

· |

poor head control; |

|

· |

abdominal breathing, also known as diaphragmatic or belly breathing, which is characterized by breathing through the contracting of the diaphragm rather than the chest; |

|

· |

bulbar muscle weakness, which is exhibited by a weak cry, difficulty swallowing and aspiration; and |

|

· |

the inability to sit unsupported. |

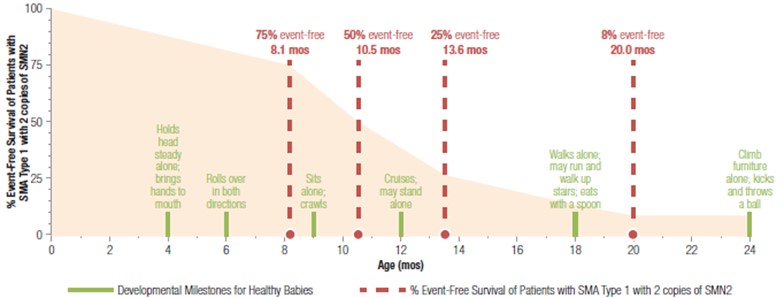

In an independent, peer‑reviewed natural history study published by the American Academy of Neurology on SMA Type 1 in 2014, or the Finkel 2014 Study, the authors observed that the life expectancy of a child with SMA Type 1 is, for a majority of patients, less than two years. The following chart presents the percentage of children with SMA Type 1 that die or require at least 16 hours per day of ventilation support for breathing at varying ages for 14 consecutive days in the absence of acute reversible illness or perioperatively, as observed in the Finkel 2014 Study, along with major developmental milestones for a healthy baby. Another published multi‑center government funded study, or the NeuroNEXT Study, which examined the longitudinal, natural history of SMA Type 1, reconfirmed the findings from the Finkel 2014 Study on the life expectancy and developmental milestones for a child with SMA Type 1.

6

Existing Treatments for SMA

The standard of care for patients with SMA Type 1 has traditionally been limited to palliative therapies, including life‑long respiratory care, ventilator support, nutritional care, orthopedic care and physical therapy. In December 2016, the FDA approved SPINRAZATM (nusinersen), developed by Biogen and Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for the treatment of SMA. Nusinersen employs an approach for the treatment of SMA called alternative splicing, which seeks to achieve more efficient production of full‑length SMN protein from the SMN2 gene. However, we believe that there is significant interest in a gene replacement therapy that can act on the underlying defect in the primary gene (SMN1) and can provide enhanced survival and motor function benefit via a one‑time dose.

Our Product Candidate: AVXS‑101 for the Treatment of SMA

AVXS‑101 is our proprietary gene therapy product candidate for the treatment of SMA. Because SMA is a neurodegenerative disease, reduced levels of SMN protein lead to continued degeneration. The goal of AVXS‑101 is to give patients a one‑time treatment to restore the body’s production of SMN protein to prevent further degeneration. Based on observations of our Phase 1 clinical trial, we believe that AVXS‑101 also enables increased motor function and enhances survival. AVXS‑101 contains the four elements that we believe are necessary for optimal delivery and function.

Components of AVXS‑101

|

· |

A recombinant AAV9 capsid shell: a non‑integrating adeno‑associated virus capsid to deliver a functional copy of a human SMN gene to the patient’s own cells without modifying the existing DNA of the patient. Unlike many other capsids, the AAV9 capsid utilized in AVXS‑101 crosses the blood‑brain barrier, a tight protective barrier which regulates the passage of substances between the bloodstream and the brain, and into the spinal cord, thus allowing the option for intravenous administration. In addition, AAV9 has been observed in preclinical studies to efficiently target motor neuron cells when delivered via either intrathecal or intravenous administration. In AVXS‑101, the DNA contained within the capsid shell is engineered to contain the other three critical elements of AVXS‑101, with the removal of the viral DNA, which leads to a significant reduction in pathogenicity and ability to replicate. |

|

· |

A human SMN transgene: a stable, functioning SMN gene that is introduced into the cell’s nucleus. |

|

· |

Self‑complementary DNA technology: the human SMN transgene is introduced as a self‑complementary double‑stranded molecule. The inclusion of this technology enables rapid onset of effect. Typically, a single‑stranded AAV vector must wait for cell‑mediated synthesis of its complementary DNA strand to form the double‑stranded DNA unit that is required for DNA replication and subsequent protein synthesis. |

7

The self‑complementary modification overcomes this rate‑limiting step of cell‑mediated second‑strand synthesis, as the two complementary halves of the scAAV genomes will associate with each other to form the required double‑stranded DNA unit. |

|

· |

A continuous promoter: this agent activates the transgene and is designed to allow for continuous and sustained SMN gene expression. The cytomegalovirus enhanced chicken beta‑actin hybrid promoter that we utilize is a constitutive, or “always on” promoter that has been observed to increase transgene expression from AAV vectors compared to other promoters. |

Clinical Development of AVXS‑101

We are currently developing AVXS‑101 for the treatment of SMA Type 1 through intravenous administration and SMA Type 2 for intrathecal administration. We intend to initiate three additional studies to further evaluate AVXS-101, including in new SMA patient populations.

Pivotal Clinical Trial for SMA Type 1

In September 2017, based on the FDA's review of our clinical, non-clinical and chemistry, manufacturing and controls, or CMC, data, including a potency assay of AVXS-101, we initiated our pivotal trial of AVXS-101 for patients with SMA Type 1 using the IV formulation produced using our current good manufacturing practice, or cGMP, commercial manufacturing process. Five patients have been dosed in this clinical trial to date.

The open-label, single-arm, single-dose, multi-center trial, which we call STR1VE, is designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a one-time IV infusion of AVXS-101 of 1.1 × 1014 vg/kg, which is intended to be equivalent to the proposed therapeutic dose received by the second dosing cohort in our Phase 1 clinical trial of AVXS-101 in patients with SMA Type 1.

The trial will enroll a minimum of 15 patients with SMA Type 1 who are less than six months of age at the time of gene therapy, and who have one or two copies of the SMN2 backup gene as determined by genetic testing and bi-allelic SMN1 gene deletion or point mutations. Following dosing of the first three patients in the trial, we conducted a review of the safety data of AVXS-101 from six time points (days one, two, seven, 14, 21 and 30), as well as early signals of efficacy. Based on our review and discussion with the FDA, we have initiated screening for, and begun enrolling, the remaining patients in the trial in accordance with the trial protocol.

The intent-to-treat, or ITT, population is defined as patients who are less than six months of age and symptomatic at the time of gene therapy, with two copies of the SMN2 gene as determined by genetic testing, bi-allelic SMN1 gene deletion and no c.859G>C mutation in SMN2. The intended enrollment will include at least 15 patients that meet the ITT criteria. The first three patients will be ITT patients per the trial protocol definition and will be dosed four weeks apart to assess safety and efficacy using the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders, or CHOP INTEND.

The co-primary efficacy outcome measures of the trial will include:

|

· |

The achievement of the developmental milestone of independent sitting for at least 30 seconds at 18 months of age; and |

|

· |

Event-free survival at 14 months of age, with an event defined as either death or at least 16 hours per day of required ventilation support for breathing for 14 consecutive days in the absence of acute reversible illness or perioperatively. |

8

Co-secondary outcome measures will include:

|

· |

The ability to thrive, defined as the ability to remain independent from feeding support, tolerate thin liquids and maintain weight; and |

|

· |

The ability to remain independent of ventilatory support at 18 months of age. |

The trial is projected to be conducted at 16 sites in the United States, including: Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Boston Children's Hospital, Children's Hospital Colorado, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Columbia University, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Duke University, Johns Hopkins Pediatric Neurology, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Oregon Health and Science University, Stanford University Medical Center, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, University of Utah, University of Wisconsin, and Washington University School of Medicine.

Phase 1 Clinical Trial for SMA Type 2

The open-label, dose-comparison, multi-center Phase 1 trial, which we call STRONG, is designed to evaluate the safety, optimal dosing and proof of concept for efficacy of AVXS-101 in two distinct age groups of patients with SMA Type 2, utilizing a one-time IT route of administration. The trial will enroll 27 infants and children who are symptomatic with a genetic diagnosis consistent with SMA, including the bi-allelic deletion of SMN1 and three copies of SMN2 without the SMN2 genetic modifier, who are able to sit but have no historical or current ability to stand or walk. Two patients in this clinical trial have been dosed to date.

Two dosage strengths will be evaluated and patients will be stratified into two age groups: patients less than 24 months and patients at least 24 months but less than 60 months. There will be at least a four-week interval between the dosing of the first three patients for each dose being studied and, based on the available safety data, a decision will be made whether to proceed.

• Patients in Cohort 1 will receive a dose of 6.0 × 1013 vg of AVXS-101, or Dose A. Cohort 1 will consist of three patients who are less than 24 months of age.

• If safety is established according to the Data Safety Monitoring Board, or the DSMB, the trial will proceed to Cohort 2.

• Patients in Cohort 2 will receive a dose of 1.2 X 1014 vg of AVXS-101, or Dose B. Cohort 2 will consist of three patients who are less than 60 months of age.

• If safety is established according to the DSMB, an additional 21 patients will be enrolled until the trial includes a total of (i) 12 patients less than 24 months of age and (ii) 12 patients at least 24 months, but less than 60 months, of age who have received Dose B.

According to the well-characterized natural history of the disease by the Pediatric Neuromuscular Clinical Research Network, 100 percent of children with SMA Type 2 will never walk without support, 95 percent of children will never stand without assistance and more than 30 percent will die by 25 years of age. Additionally, children with SMA Type 2, who are between 24 and 60 months of age with 3 copies of the SMN2 gene, experienced a mean decrease of 0.33 points on the Hammersmith Function Motor Scale Expanded over a 12-month period at first evaluation.

Outcome Measures for Patients Less than 24 Months of Age

• The primary outcome measure for patients less than 24 months of age at the time of dosing is the achievement of the ability to stand without support for at least three seconds.

• The secondary outcome measure is the proportion of patients who achieve the ability to walk without assistance, defined as taking at least five steps independently while displaying coordination and balance.

• Developmental abilities, including motor function, will be evaluated as exploratory objectives.

9

Outcome Measures for Patients Between 24 and 60 Months of Age

• The primary outcome measure for patients between 24 months and 60 months of age at the time of dosing is the achievement of change in Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded from baseline.

• The secondary outcome measure is the proportion of patients who achieve the ability to walk without assistance, defined as taking at least five steps independently displaying coordination and balance.

• Developmental abilities, including motor function, will be evaluated as exploratory objectives.

The trial is projected to be conducted at 11 sites in the United States, including Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Boston Children's Hospital, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Johns Hopkins Pediatric Neurology, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Stanford University Medical Center, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, University of Utah and Washington University School of Medicine.

Planned Pivotal Trial of AVXS-101 in SMA Type 1 in Europe

We intend to initiate a pivotal trial of AVXS-101 for the treatment of SMA Type 1 in Europe in the first half of 2018. The planned trial design, which incorporates scientific advice from the EMA, is expected to reflect a single-arm design, using natural history of the disease as a comparator, and is expected to enroll approximately 30 patients with SMA Type 1 who are less than six months of age at the time of gene therapy. The trial is designed to evaluate safety and efficacy of a one-time IV dose of AVXS-101, including achievement of motor milestones, specifically patients’ ability to sit unassisted, as well as an efficacy measure defined by the time from birth to an “event,” defined as death or requiring at least 16 hours per day of ventilation support for breathing for greater than two weeks in the absence of an acute reversible illness, or perioperatively.

Completed Phase 1 Clinical Trial for SMA Type 1

In April 2014, an open‑label, dose‑escalation Phase 1 clinical trial of AVXS‑101 in patients with SMA Type 1 was initiated as an investigator‑sponsored trial at NCH under an IND, held by Dr. Jerry Mendell, the principal investigator at NCH. We completed the transfer of the IND to AveXis in November 2015. The trial design allowed for the enrollment of up to 15 patients across a maximum of three dosing cohorts. Key inclusion criteria included the presence of typical clinical symptoms before 6 months of age, SMA Type 1 patients with bi‑allelic SMN1 gene deletions or mutations (all patients in the trial had bi‑allelic deletions) and with two copies of the SMN2 backup gene as confirmed by genetic testing in an independent laboratory. Confirmed absence of the Exon 7 genetic modifier (c.859G>C) was made through the laboratory of Dr. Tom Prior, the scientist who described the impact of this mutation on clinical phenotype. Furthermore, all patients were re‑tested at an independent laboratory to re‑confirm all genetic results. Additionally, patients must have been no older than nine months of age (for the first nine patients) and six months of age (for the last six patients) at the time of vector infusion.

The primary outcome measure of our Phase 1 clinical trial was safety and tolerability. The key efficacy measures were defined as the time from birth to an “event,” which was defined as either death or at least 16 hours per day of required ventilation support for breathing for 14 consecutive days in the absence of acute reversible illness or perioperatively, and video confirmed achievement of ability to sit unassisted. We also assessed several exploratory objective measures in the clinical trial. These exploratory measures were included to assess additional testing protocols on patients in an effort to identify objective testing criteria for measuring the results of the therapy. These exploratory tests included administering a standard motor milestone development survey and CHOP INTEND, the need for pulmonary and feeding support, evaluation of swallowing function, compound motor action potentials testing (CMAP), motor unit number estimation testing (MUNE), non‑invasive electrical impedance myography testing (EIM) and “ability captured through interactive video evaluation‑mini” testing (ACTIVE‑mini).

Once a patient met the screening criteria for the clinical trial, the patient received a one‑time dose of AVXS‑101, by intravenous injection over a one‑hour period. The patient remained at NCH for 48 hours after dosing for monitoring, and then was discharged. For one month after dosing, weekly follow‑up evaluations were conducted. After

10

the first month, additional monthly evaluations were conducted for the first 12 months followed by quarterly evaluations for the remaining 12 months.

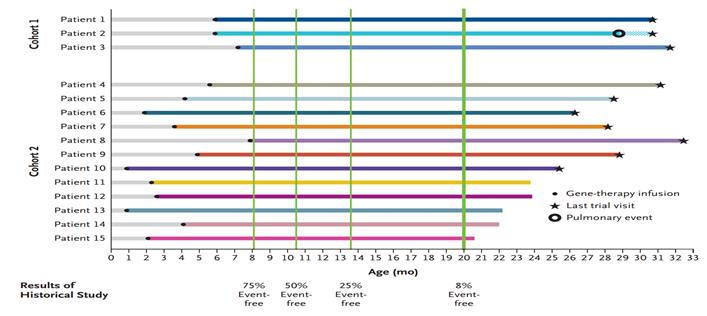

Clinical Results

We fully enrolled our Phase 1 trial, having dosed a total of 15 patients in the trial. The first cohort, which completed dosing in September 2014, consisted of three infants who received a dose of AVXS‑101 administered at the low dose, based on the patient’s weight, or the low-dose cohort. The second cohort, which completed dosing in December 2015, consisted of 12 infants who received the proposed therapeutic dose of AVXS‑101, or the proposed therapeutic dose-cohort.

As of August 7, 2017, all 15 patients (100%) in the trial reached 20 months of age without experiencing an “event,” described as death or at least 16 hours per day of required ventilation support for breathing for 14 consecutive days in the absence of acute reversible illness or perioperatively, in contrast to the 8% event free rate at this time point demonstrated in an independent, peer-reviewed natural history study for patients with SMA Type 1. All 15 patients experienced improvement from baseline in motor skills measured by their CHOP INTEND scores and such improvement appeared to be dose‑dependent. As of August 7, 2017, we have observed AVXS‑101 to be generally well‑tolerated.

As of August 7, 2017, all patients in the proposed therapeutic dose‑cohort were event‑free. The median age at last follow-up was 25.7 months and 30.7 months for patients in the proposed therapeutic-dose cohort and low-dose cohort, respectively. As previously reported, one patient in the low‑dose cohort, had a pulmonary event in the third quarter of 2016 at the age of 28.8 months. The patient had increased use of bi‑level positive airway pressure, or BiPAP, in advance of surgery related to hypersalivation, a condition experienced by some SMA patients; the event was determined upon independent review to represent progression of disease and not to be related to the use of AVXS‑101. This patient completed the final trial visit in September 2016 and as of that time point, BiPAP use was below the 16 hours per day usage that defines the threshold for the survival endpoint. Although the results of the Finkel 2014 Study were not pre‑specified as a comparator for our trial, we believe that this compilation of data from patients with SMA Type 1 provides a useful context to consider the results of our trial to date. This peer‑reviewed publication reported that 8% of patients with SMA Type 1 were event‑free at 20.0 months of age. The lethality of the disease is further supported by the recent NeuroNEXT Study, which indicated a median time to death or tracheostomy for ventilation support for breathing SMA Type 1 patients from birth of eight months. The following figure shows survival data of all 15 patients enrolled in the clinical trial through August 7, 2017.

The CHOP INTEND test is designed to evaluate the motor skills of patients with SMA Type 1 by testing 16 items, which measure the movement of various body segments. As of August 7, 2017, 11 of 12 patients (92%) in the proposed therapeutic dose-cohort have achieved and maintained CHOP INTEND scores of ≥40 points. Two patients who have achieved CHOP INTEND scores of at least 60 points, which is considered to be normal, achieved the

11

maximum CHOP INTEND score of 64. The Finkel 2014 Study reported that patients with SMA Type 1 have an average annual decrease of 1.27 points in their CHOP INTEND score. The NeuroNEXT Study indicated a mean decline of 10.5 points in CHOP INTEND scores over a one-year period in untreated SMA Type 1 patients, highlighting the rapid loss of motor function occurring early in the disease course. All 15 patients enrolled in our Phase 1 trial experienced improvement from baseline in motor skills measured by their CHOP INTEND scores and such improvement appeared to be dose‑dependent. As of August 7, 2017, the patients in cohorts 1 and 2 had increased scores from baseline on the CHOP INTEND scale and maintained these changes during the study. Patients in cohort 2 had mean increases of 9.8 points at 1 month and 15.4 points at 3 months. At the study cutoff on August 7, 2017, patients in cohort 1 had a mean increase of 7.7 points from a mean baseline of 16.3 points, and those in cohort 2 had a mean increase of 24.6 points from a mean baseline of 28.2 points. As of August 7, 2017, 10 out of 15 patients treated had completed their 2-year follow-up after receipt of their AVXS-101 gene therapy. Based on our observations to date, we believe that increases in CHOP INTEND motor assessments appear to be age, baseline CHOP INTEND score and dose‑dependent. We believe that there may be a dose response, based on our observation of CHOP INTEND scores of patients receiving the proposed therapeutic dose as compared to patients receiving the low dose because, as a group, the patients receiving the proposed therapeutic dose appear to be demonstrating a larger average CHOP INTEND score increase.

Patients with SMA Type 1 entered the trial at different ages, stages of disease progression and levels of motor function that can result in significant variability in baseline CHOP INTEND scores from patient to patient. Additionally, month‑to‑month variability in CHOP INTEND scores can be influenced by factors that are not related to study treatment. Examples of these factors include upper respiratory tract infections and fractured limbs, which may preclude the testing of some elements of the CHOP INTEND assessment. Our observations are consistent with the Finkel 2014 Study in which baseline CHOP INTEND scores also demonstrated significant variability. While the improvements seen with AVXS‑101 in the proposed therapeutic dose cohort have never been observed in the natural history population, we believe observing change in CHOP INTEND scores over time is beneficial.

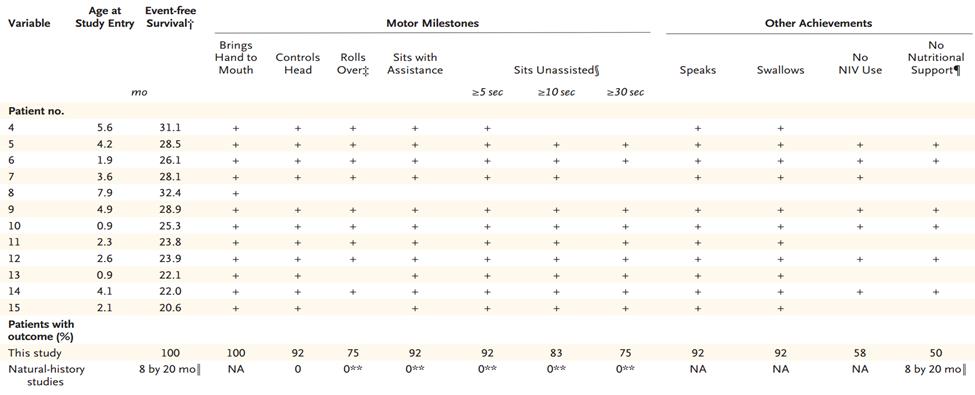

The natural history of SMA Type 1 is marked by the inability to achieve or maintain developmental motor milestones. An independent, peer‑reviewed natural history study of developmental milestones in SMA Type 1 published in Neuromuscular Disorders in 2016, or the De Sanctis 2016 Study, reported that prolongation of survival with supportive care does not impact achievement of motor milestones. As observed in the De Sanctis 2016 Study, a child with SMA Type 1 with symptom onset prior to six months of age will not reach any major milestones such as sitting, crawling, standing and walking, and the highest milestone achieved is seen in the infant’s first visit followed by a rapid decline. In contrast, patients in the proposed therapeutic‑dose cohort consistently achieved and maintained key developmental motor milestones. As of August 7, 2017, 11 of 12 patients (92%) in the proposed therapeutic‑dose cohort achieved head control, nine of 12 patients (75%) could rollover and 11 of 12 patients (92%) could sit with assistance. For the end‑of‑study assessment at January 20, 2017 and subsequent assessments, including the August 7, 2017 assessment, we evaluated three validated and well‑established measures of sitting unassisted for periods of increasing duration. At August 7, 2017, 11 of 12 patients (92%) could sit unassisted for at least five seconds, 10 of 12 patients (83%) could sit unassisted for at least 10 seconds and nine of 12 patients (75%) could sit unassisted for 30 seconds or more. Two patients could walk independently and each had achieved earlier and important developmental milestones such as standing with support, standing alone and walking with support. These milestone achievements were assessed and adjudicated by an independent, third‑party reviewer using video evidence. The results of this process are included in the chart below.

12

* At baseline, none of the patients in cohort 2 had achieved any of the listed motor milestones except for bringing a hand to the mouth. As of August 7, 2017, the majority of these patients had reached at least one major motor milestone. No patients in cohort 1 are listed, since none attained any motor milestones. NA denotes not available, and NIV noninvasive ventilation. Plus signs indicate achievement of milestone.

† Event‑free survival (the primary efficacy outcome) was defined as the age at the last follow‑up at which patients were free of ventilatory support, which was defined as the need for ventilation for at least 16 hours per day for at least 14 consecutive days.

‡ According to item 20 on the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, rolling over is defined as movement of at least 180 degrees both left and right from a position of lying on the back.

§ Sitting unassisted for at least 5 seconds is in accordance with the criteria of item 22 on the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development gross motor subtest and surpasses the 3‑second count that is used as a basis for sitting (test item 1) on the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale–Expanded for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA). Sitting unassisted for at least 10 seconds is in accordance with the criteria used in the World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Sitting unassisted for at least 30 seconds defines functional independent sitting and is in accordance with the criteria of item 26 on the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development gross motor subtest.

¶ Nutritional support refers to the placement of either a gastrostomy tube or a nasogastric tube, as determined by the preference of the parents or the primary physician. Once enrolled in the study, all the patients who required nutritional support underwent gastrostomy‑tube placement, and none were removed during the study.

‖ Data are from Finkel et al.

** Data are from De Sanctis et al.

The primary outcome measure for our Phase 1 trial of AVXS‑101 was safety. As of August 7, 2017, a total of 56 serious adverse events, or SAEs, were observed in 13 patients. Of these 56 SAEs, there were two treatment‑related SAEs in two patients. There were also three treatment‑related non‑serious adverse events reported in two patients. All five treatment‑related SAEs and AEs were clinically asymptomatic liver function enzyme, or LFE, elevations.

The treatment‑related SAEs consisted of two patients that experienced elevated LFEs, which were each assessed as a Grade 4 event under the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events on the basis of laboratory values. We observed the first of these treatment‑related SAEs in the first patient dosed with AVXS‑101 in our Phase 1 clinical trial. After the onset of elevated LFEs, this patient was given a prednisolone regimen starting at 2 mg/kg daily and tapering off over time as LFEs returned to normal. After the first patient, we revised our clinical protocol to include pre‑treatment with prednisolone at 1 mg/kg/day starting one day prior to the gene transfer in order to mitigate the T‑cell immune response against AAV9 and the corresponding increase in LFEs. As of August 7, 2017, following this protocol change, out of the remaining 14 patients in our Phase 1 clinical trial, 11 patients had no reported adverse events related to elevations in LFEs, two patients had Grade 1 or 2 elevations in LFEs, and one patient experienced a Grade 4 elevation in LFE on the basis of laboratory values. We observed that this Grade 4 LFE patient had a concomitant viral infection and required additional prednisolone therapy until the LFEs returned to the normal range. We believe that the pretreatment with prednisolone has generally been effective in reducing the incidence and degree of elevated LFEs. As of August 7, 2017, all AEs and SAEs related to elevated LFEs were isolated elevations in serum transaminases, clinically asymptomatic and resolved with prednisolone treatment. There were no elevations in total bilirubin, gamma‑glutamyl transferase or alkaline phosphatase and the conditions that constitute Hy’s law were not met.

13

Based on the 15 patients dosed as of August 7, 2017, we observed AVXS‑101 to be generally well‑tolerated. As previously reported, a total of five adverse events, or AEs, in four patients were deemed treatment‑related. Of these, two were SAEs experienced by two patients, and three were non‑serious AEs experienced by two patients. All consisted of clinically asymptomatic liver enzyme elevations and were resolved with prednisolone treatment. There were no clinically significant elevations of gamma‑glutamyl transferase, alkaline phosphatase or bilirubin and, as such, the conditions that constitute Hy’s Law were not met. Other non‑treatment related AEs were expected and were associated with SMA. A cumulative total of 297 AEs (5 treatment‑related AEs and 292 non‑treatment related AEs) were reported as of August 7, 2017, following monitoring and source verification. Of these, 56 were determined to be SAEs and 241 were non‑serious AEs.

Preclinical Studies

Preliminary preclinical proof of concept and safety and tolerability studies of the intravenous delivery method were conducted at NCH and in conjunction with the Mannheimer Foundation for non‑human primate studies. In a mouse model of SMA Type 1, it was observed that a single intravenous injection of AVXS‑101 in mice improved body weight and motor functions, while also extending the median lifespan of the treated mice from 14 days to greater than 250 days with 30% of mice surviving over 400 days, compared to untreated mice, in a dose‑responsive manner. In these studies, a minimally effective dosage was determined to be 6.7 × 1013 vg/kg which increased median lifespan to 28 days. Escalating the dosage to 2.0 × 1014 vg/kg increased the median lifespan of the SMA mouse model greater than 250 days. Further increasing the dosage to 3.3 × 1014 vg/kg also resulted in the SMA mouse model to have a median lifespan greater than 250 days. The 2.0 × 1014 vg/kg and 3.3 × 1014 vg/kg dosages appeared to be indistinguishable, with animals showing normal motor function. In a preclinical study of non‑human primates, it was observed that a single intravenous injection of AVXS‑101 led to sustained human SMN transgene expression in the spinal cord as well as in multiple organs and muscles, when evaluated 24 weeks after injection of AVXS‑101. AVXS‑101 has also been studied in multiple safety and tolerability studies in mice and non‑human primates and no evidence of toxicity was observed for up to 24 weeks after injection of AVXS‑101.

In addition, preliminary preclinical proof of concept (efficacy and safety) studies of the intrathecal delivery method were conducted at NCH. It was observed that in mice with SMA Type 1, a single intrathecal injection of AVXS‑101 at a maximum dosage level of 3.3 × 1013 vg/kg, improved body weight and motor functions, and most notably extended the median lifespan from 18 days to 282 days, with one‑third of the mice surviving past 400 days. In the SMA mouse model, it was observed that a single intrathecal injection of scAAV9 containing a green fluorescent protein targeted between 21% to 41% and 46% to 72% of motor neurons in the spinal cord at the lowest dosage level and the highest dosage level, respectively. In non‑human primates, it was observed that a single intrathecal injection of scAAV9 containing green fluorescent protein at a dose of 1.0 × 1013 vg/kg targeted 29%, 53% and 73% of cervical, thoracic and lumbar motor neurons, respectively. With tilting for ten minutes in the Trendelenburg position, such targeting increased to 55%, 62% and 80% of cervical, thoracic and lumbar motor neurons, respectively. In swine, NCH and collaborators at Ohio State University designed a small hairpin RNA that targeted porcine SMN and left human SMN intact, which reduced expression of porcine SMN. It was observed that the administration of AVXS‑101 resulted in robust production of human SMN protein and significant increases in motor function. When delivered prior to the onset of motor function decline, AVXS‑101 prevented the majority of SMA symptoms, demonstrated by motor function testing as well as electrophysiological evaluation. When delivered at the onset of SMA symptoms, AVXS‑101 halted further progression and there were improvements in motor function as well as electrophysiological evaluation of motor units.

Future Applications and Opportunities

Based on preclinical data and the clinical data from our Phase 1 clinical trial for SMA Type 1, we believe AVXS‑101 may also have utility in other types of SMA, which result from the same genetic defect as SMA Type 1 as it addresses the root cause of the disease. In addition to our ongoing Phase 1 clinical trial for SMA Type 2, we intend to conduct the following additional clinical trials to further evaluate AVXS-101, including in new SMA patient populations:

14

|

· |

Pre-Symptomatic SMA Types 1, 2, 3 (SPRINT): The planned multi-national trial is expected to enroll approximately 44 patients with two, three and four copies of SMN2 who are less than six weeks of age and who are pre-symptomatic at the time of gene therapy. The trial is designed to evaluate appropriate clinical endpoints, including developmental milestones, survival, bulbar function and safety, of a one-time IV infusion of AVXS-101. We expect to initiate the trial in the first half of 2018, and will provide more trial design details at the time of initiation. |

|

· |

Pediatric “All Comers” with SMA Types 1, 2, 3 (REACH): The planned multi-national trial is expected to enroll approximately 50 patients between approximately six months and 18 years of age who do not qualify for other AVXS-101 trials at the time of gene therapy. The trial is designed to evaluate a one-time IT dose of AVXS-101. We expect to initiate the trial late in the fourth quarter of 2018 or early 2019, and will provide more trial design details at the time of initiation. |

In addition to our programs in SMA, we also intend to identify, acquire, develop and commercialize novel product candidates for the treatment of other rare and life‑threatening neurological genetic diseases that we believe can be treated with gene therapy. In June 2017, we announced that we had entered into an exclusive, worldwide license agreement with REGENXBIO for the development and commercialization of gene therapy using AAV9 to treat two rare neurological monogenic disorders: Rett syndrome and genetic ALS. We also licensed from NCH preclinical data suggesting promising safety and efficacy of gene therapy treatments for these disorders using AAV9, generated by our Chief Scientific Officer, Dr. Brian Kaspar. See “—Our Collaboration and License Agreements—Strategic Collaborators and Relationships—Preclinical Programs for Rett Syndrome and Genetic ALS.” We expect to move forward with initiating IND-enabling studies in both Rett syndrome and genetic ALS and submit IND applications for both indications in late 2018 or early 2019. Current treatments for Rett syndrome and genetic ALS do not target the genetic cause of either disease, leaving what we believe to be a significant unmet need.

Rett Syndrome

Rett syndrome is a devastating, rare neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by slowed growth, loss of normal movement and coordination and loss of communication skills. Rett syndrome is an X-linked dominant genetic disorder caused by mutations in the gene for methyl-CpG-binding protein 2, or MECP2, which results in problems with the MECP2 protein, which is critical for normal brain development. Rett syndrome is very rare in males, but occurs in approximately one of every 10,000 female births in the United States with an estimated U.S. prevalence of approximately 8,500 based on applying natural history survival rates to historical births. Affected infants usually begin to show signs and symptoms between six and 18 months of age. Current treatments for patients with Rett syndrome offer only symptomatic relief and do not target the genetic cause of the disease.

Our Product Candidate: AVXS-201 for the Treatment of Rett Syndrome

We are conducting preclinical studies of AVXS-201, our proprietary gene therapy product candidate for the treatment of Rett syndrome. In completed preclinical studies using rodent models, it was observed that gene therapy to introduce re-expression of the MECP2 gene improved survival and improved the behavioral abnormalities associated with the disease model, including motor function. AVXS-201, like AVXS-101, is composed of a recombinant AAV9 capsid shell, with a human transgene and a continuous promoter specifically designed for optimal MECP2 expression.

In a preclinical mouse model, we observed that certain doses of AVXS-201, delivered once into the CSF, increased the median lifespan of a Rett syndrome mouse model to over 200 days, compared to 66 days for untreated mice. In a preclinical study of non-human primates, we observed that weight, blood parameters, and liver enzymes remained normal up to 18 months after a single lumbar intrathecal injection of AVXS-201. We have observed no evidence of toxicity in wild-type mice treated with AVXS-201, and we observed no indications of tissue damage or disease in non-human primates post-injection. In both the preclinical mouse studies and preclinical non-human primate studies, we observed widespread targeting of AVXS-201 throughout the whole central nervous system after a single injection, as assessed by immunohistochemistry, immunocytochemistry, in situ hybridization and western blotting throughout various brain regions.

15

We have generated AVXS-201 by leveraging our manufacturing platform and are utilizing a process very similar to AVXS-101. We have successfully completed engineering lots, along with a cGMP manufacturing run intended for clinical use, and we have also developed key analytical assays suited for AVXS-201.

Genetic ALS

ALS is a progressive, fatal, neurodegenerative disease that affects motor neurons in the brain and the spinal cord. Symptoms of ALS include progressive weakness and atrophy of muscles controlling voluntary movement, swallowing, speech and breathing, and most commonly develops between 40 and 70 years of age. Genetic forms of ALS comprise five to ten percent of all ALS cases, and approximately twenty percent of genetic ALS cases are caused by mutations in the SOD1 gene, which are toxic to motor neurons. In 2013, there were 15,908 patients with “definite ALS” in the United States, a prevalence rate of approximately five of every 100,000 persons. Approximately 800 to 1,600 of these cases were due to genetic causes of ALS.

Our Product Candidate: AVXS-301 for the Treatment of Genetic ALS

We are conducting preclinical studies of AVXS-301, our proprietary gene therapy product candidate for the treatment of genetic ALS. In previous studies in the laboratory of Dr. Kaspar at NCH, we utilized AAV9 carrying a green fluorescent protein reporter to deliver a short hairpin RNA, or shRNA, targeting the mutant human SOD1 transgene. We observed improved disease outcome in two different mouse models of ALS following a one-time administration, even when delivered at the time of disease onset. We also observed that this treatment was safe and well-tolerated in wild-type mice. Based on these preclinical studies, we developed AVXS-301, which, like AVXS-101, is composed of an AAV9 capsid shell. In preclinical studies of an AAV9 vector with a SOD1 shRNA expression cassette and a non-coding stuffer sequence instead of GFP, we observed efficient SOD1 downregulation in vitro, and in vivo efficacy in delaying disease onset and progression.

We have studied the administration of AVXS-301 both intravenously and directly into the cerebral spinal fluid, or CSF, in mice that overexpress human mutant SOD1. We observed that both administrations improved rotarod motor performance and hindlimb grip strength. In our preclinical mouse studies, we observed that a single administration of AVXS-301 directly into the CSF resulted in a greater than 51% increase in survival in the most severe ALS mouse model. We also conducted preclinical studies in non-human primates, where we observed that a single lumbar intrathecal infusion of AVXS-301 resulted in approximately 90% SOD1 reduction throughout the monkey spinal cord. Results from other studies in the field suggest that SOD1 may be involved in more than SOD1-linked disease mutations, which we believe may increase the scope of patients that may be treatable with AVXS-301.

We have developed a manufacturing process for both AVXS-201 and AVXS-301 by leveraging our AVXS-101 manufacturing platform. As such, we are utilizing a manufacturing process very similar to AVXS-101. We have successfully completed engineering lots for both AVXS-201 and AVXS-301. We intend to complete cGMP clinical manufacturing runs for both products in the near future.

Manufacturing

We have established our own commercial scale cGMP‑compliant manufacturing facility to enhance supply chain control, increase supply capacity for clinical trials and ensure commercial demand is met in the event that AVXS‑101 receives marketing approval. We intend to use our cGMP manufacturing process for all clinical and commercial production of AVXS-101. We manufacture AVXS‑101 using adherent human embryonic kidney, or HEK, 293 cells. HEK293 cells have been used successfully to manufacture numerous other gene therapy candidates that have been tested or are currently being tested in other clinical trials to date. We use a novel and scalable adherent cell culture approach for AAV9 vector production that can more reliably produce product and has greater surface area to potentially increase productivity relative to traditional flat stock approaches.

Although we anticipate that our manufacturing facility will be the primary production site to meet projected clinical and commercial demand, we will continue to evaluate, and will pursue as needed, potential third parties and/or additional internal sources of redundant manufacturing capacity to provide multiple long‑term supply alternatives to

16

meet commercial demand in the event that AVXS‑101 receives marketing approval and for our other programs. We continue to utilize our internal process science group and work with third parties in order to evaluate and develop manufacturing process improvements that may increase the productivity and efficiency of our manufacturing process.

Competition

The biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries are highly competitive. In particular, the field of gene therapy is characterized by rapidly advancing technologies, intense competition and a strong emphasis on proprietary products. We face substantial competition from many different sources, such as large and specialty pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, academic research institutions, government agencies and public and private research institutions.