UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 8-K

CURRENT REPORT

Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): February 1, 2016

ROYAL ENERGY RESOURCES, INC.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

| Delaware | 000-52547 | 11-3480036 | ||

| (State

or other jurisdiction of incorporation) |

(Commission

file number) |

(I.R.S.

Employer Identification Number) |

56 Broad Street, Suite 2, Charleston, SC 29401

(Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code)

(843) 900-7693

(Registrant’s telephone number, including area code)

Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions:

[ ] Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425)

[ ] Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12)

[ ] Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b))

[ ] Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4c))

Section 3 – Securities and Trading Markets

Item 3.02 Unregistered Sales of Equity Securities.

On February 1, 2016, Royal Energy Resources, Inc. (the “Company”) commenced a private offering of its common stock under SEC Rule 506, under which the Company is offering up to 2,187,500 shares of common stock at a price of $8.00 per share, for maximum gross proceeds of $17,500,000. The Company expects to use the proceeds to increase its investment in Rhino Resource Partners, LP, to fund the acquisition of other natural resource assets, and for general working capital purposes.

| 2 |

SIGNATURES

In accordance with the requirements of the Exchange Act, the registrant caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized.

| ROYAL ENERGY RESOURCES, INC. | ||

| Date: February 5, 2016 | By: | /s/ William L. Tuorto |

| William L. Tuorto, Chief Executive Officer | ||

| 3 |

EXHIBIT A

Description of Business of Rhino Resource Partners, LP

The following description of Rhino’s business and assets derived from Rhino’s Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2014, as filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 11, 2015, and its subsequent Form 10-Q’s and 8-K’s. The discussion has been modified to delete references to certain assets that were disposed of after the Form 10-K was filed.

For a more complete description of Rhino’s business, financial statements, management, executive compensation, related party transactions, and other factors, investors should review Rhino’s reports filed with the SEC available at www.sec.gov, including:

| Report | File Date | |

| Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2014 | March 11, 2015 | |

| Form 10-Q for the three months ended March 31, 2015 | May 6, 2015 | |

| Form 10-Q for the six months ended June 30, 2015 | August 7, 2015 | |

| Form 10-Q for the nine months ended September 30, 2015 | November 6, 2015 |

GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS

ash: Inorganic material consisting of iron, alumina, sodium and other incombustible matter that are contained in coal. The composition of the ash can affect the burning characteristics of coal.

assigned reserves: Proven and probable reserves that have the permits and infrastructure necessary for mining.

as received: Represents an analysis of a sample as received at a laboratory.

Btu: British thermal unit, or Btu, is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water one degree Fahrenheit.

Central Appalachia: Coal producing area in eastern Kentucky, Virginia and southern West Virginia.

coal seam: Coal deposits occur in layers typically separated by layers of rock. Each layer is called a “seam.” A seam can vary in thickness from inches to a hundred feet or more.

coke: A hard, dry carbon substance produced by heating coal to a very high temperature in the absence of air. Coke is used in the manufacture of iron and steel.

fossil fuel: A hydrocarbon such as coal, petroleum or natural gas that may be used as a fuel.

GAAP: Generally accepted accounting principles in the United States.

| 4 |

high-vol metallurgical coal: Metallurgical coal that has a volatility content of 32% or greater of its total weight.

Illinois Basin: Coal producing area in Illinois, Indiana and western Kentucky.

limestone: A rock predominantly composed of the mineral calcite (calcium carbonate (CaCO3)).

lignite: The lowest rank of coal. It is brownish-black with high moisture content commonly above 35% by weight and heating value commonly less than 8,000 Btu.

low-vol metallurgical coal: Metallurgical coal that has a volatility content of 17% to 22% of its total weight.

mid-vol metallurgical coal: Metallurgical coal that has a volatility content of 23% to 31% of its total weight.

Metallurgical, or “met”, coal: The various grades of coal suitable for carbonization to make coke for steel manufacture. Its quality depends on four important criteria: volatility, which affects coke yield; the level of impurities including sulfur and ash, which affects coke quality; composition, which affects coke strength; and basic characteristics, which affect coke oven safety. Metallurgical coal typically has a particularly high Btu but low ash and sulfur content.

net mineral acre: The product of (i) the percentage of oil and natural gas mineral rights owned in a given tract of land and (ii) the total surface acreage of such tract.

non-reserve coal deposits: Non-reserve coal deposits are coal-bearing bodies that have been sufficiently sampled and analyzed in trenches, outcrops, drilling and underground workings to assume continuity between sample points, and therefore warrant further exploration stage work. However, this coal does not qualify as a commercially viable coal reserve as prescribed by standards of the SEC until a final comprehensive evaluation based on unit cost per ton, recoverability and other material factors concludes legal and economic feasibility. Non-reserve coal deposits may be classified as such by either limited property control or geologic limitations, or both.

Northern Appalachia: Coal producing area in Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia.

overburden: Layers of earth and rock covering a coal seam. In surface mining operations, overburden is removed prior to coal extraction.

preparation plant: Usually located on a mine site, although one plant may serve several mines. A preparation plant is a facility for crushing, sizing and washing coal to prepare it for use by a particular customer. The washing process separates higher ash coal and may also remove some of the coal’s sulfur content.

probable (indicated) coal reserves: Coal reserves for which quantity and grade and/or quality are computed from information similar to that used for proven (measured) reserves, but the sites for inspection, sampling, and measurement are farther apart or are otherwise less adequately spaced. The degree of assurance, although lower than that for proven (measured) reserves, is high enough to assume continuity between points of observation.

proven (measured) coal reserves: Coal reserves for which (a) quantity is computed from dimensions revealed in outcrops, trenches, workings or drill holes; grade and/or quality are computed from the results of detailed sampling and (b) the sites for inspection, sampling and measurement are spaced so closely and the geologic character is so well defined that size, shape, depth and mineral content of reserves are well-established.

reclamation: The process of restoring land to its prior condition, productive use or other permitted condition following mining activities. The process commonly includes “re-contouring” or reshaping the land to its approximate original contour, restoring topsoil and planting native grass and shrubs. Reclamation operations are typically conducted concurrently with mining operations, but the majority of reclamation costs are incurred once mining operations cease. Reclamation is closely regulated by both state and federal laws.

| 5 |

recompletion: The process of re-entering an existing wellbore that is either producing or not producing and completing new oil and natural gas reservoirs in an attempt to establish or increase existing production.

reserve: That part of a mineral deposit which could be economically and legally extracted or produced at the time of the reserve determination.

steam coal: Coal used by power plants and industrial steam boilers to produce electricity, steam or both. It generally is lower in Btu heat content and higher in volatile matter than metallurgical coal.

sulfur: One of the elements present in varying quantities in coal that contributes to environmental degradation when coal is burned. Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is produced as a gaseous by-product of coal combustion.

surface mine: A mine in which the coal lies near the surface and can be extracted by removing the covering layer of soil overburden. Surface mines are also known as open-pit mines.

tons: A “short” or net ton is equal to 2,000 pounds. A “long” or British ton is 2,240 pounds. A “metric” tonne is approximately 2,205 pounds. The short ton is the unit of measure referred to in this report.

Western Bituminous region: Coal producing area located in western Colorado and eastern Utah.

We are a diversified energy limited partnership formed in Delaware that is focused on coal and energy related assets and activities, including energy infrastructure investments. We produce, process and sell high quality coal of various steam and metallurgical grades from multiple coal producing basins in the United States. We market our steam coal primarily to electric utility companies as fuel for their steam powered generators. Customers for our metallurgical coal are primarily steel and coke producers who use our coal to produce coke, which is used as a raw material in the steel manufacturing process. In addition to operating coal properties, we manage and lease coal properties and collect royalties from such management and leasing activities. In addition, we have expanded our business to include infrastructure support services, including the formation of a service company to provide drill pad construction for operators in the Utica Shale as well as other joint venture investments to provide for the transportation of hydrocarbons and drilling support services in the Utica Shale region. We have also invested in joint ventures that will provide sand for fracking operations to drillers in the Utica Shale region and other oil and natural gas basins in the United States.

We have a geographically diverse asset base with coal reserves located in Central Appalachia, Northern Appalachia, the Illinois Basin and the Western Bituminous region. As of December 31, 2014, we controlled an estimated 480.0 million tons of proven and probable coal reserves, consisting of an estimated 425.1 million tons of steam coal and an estimated 54.9 million tons of metallurgical coal. In addition, as of December 31, 2014, we controlled an estimated 290.0 million tons of non-reserve coal deposits. As discussed further below, Rhino Eastern LLC, a joint venture in which we had a 51% membership interest and for which we served as manager, was dissolved in January 2015. As part of this dissolution, we received approximately 34 million tons of premium metallurgical coal reserves, which we have included in the proven and probable reserves listed above since the joint venture and its operations were effectively dissolved as of December 31, 2014.

As of December 31, 2014, we operated nine mines, including four underground and five surface mines, located in Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia and Utah. The number of mines that we operate will vary from time to time depending on a number of factors, including the existing demand for and price of coal, depletion of economically recoverable reserves and availability of experienced labor.

| 6 |

Due to the prolonged weakness in the U.S. coal markets and the dim prospects for an upturn in the coal markets in the near term, in the fourth quarter of 2014, we performed a comprehensive review of our current coal mining operations as well as potential future development projects to ascertain whether any of our investments were no longer recoverable. We identified various properties, projects and operations that were potentially impaired based upon changes in our strategic plans, market conditions or other factors. We recorded approximately $45.3 million of asset impairment and related charges for the year ended December 31, 2014. We also recorded an additional $5.9 million impairment charge as of December 31, 2014 related to the January 2015 dissolution of our Rhino Eastern joint venture that is discussed further below. Please see “Item 7. Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations”, for a detailed discussion of these asset impairment and related charges.

In January 2015, we completed a Membership Transfer Agreement (the “Transfer Agreement”) with an affiliate of Patriot Coal Corporation (“Patriot”) that terminated the Rhino Eastern joint venture. Pursuant to the Transfer Agreement, Patriot sold and assigned its 49% membership interest in the Rhino Eastern joint venture to us and, in consideration of this transfer, Patriot received certain fixed assets, leased equipment and coal reserves associated with the mining area previously operated by the Rhino Eastern joint venture. Patriot also assumed substantially all of the active workforce related to the Eagle mining area that was previously employed by the Rhino Eastern joint venture. We retained approximately 34 million tons of coal reserves that are not related to the Eagle mining area as well as a prepaid advanced royalty balance of $6.3 million. As part of the closing of the Transfer Agreement, we and Patriot agreed to a dissolution payment based upon a final working capital adjustment calculation as defined in the Transfer Agreement.

Excluding results from the Rhino Eastern joint venture, for the year ended December 31, 2014, we produced approximately 3.4 million tons of coal, purchased approximately 0.1 million tons of coal and sold approximately 3.6 million tons of coal. Additionally, the Rhino Eastern joint venture produced and sold approximately 0.2 million tons of premium mid-vol metallurgical coal for the year ended December 31, 2014. Lessees produced approximately 2.9 million tons of coal from our Elk Horn coal leasing properties in eastern Kentucky for the year ended December 31, 2014. Please see Note 21 of the consolidated financial statements included elsewhere in this annual report for information regarding our reportable business segments.

Our principal business strategy is to safely, efficiently and profitably produce, sell and lease both steam and metallurgical coal from our diverse asset base in order to maintain, and, over time, increase our quarterly cash distributions. In addition, we intend to potentially diversify our operations through strategic acquisitions, including the acquisition of long-term, cash generating natural resource assets. We believe that such assets will enhance the stability of our cash flow.

History

Our predecessor was formed in April 2003 by Wexford Capital LP (“Wexford Capital”, and together with certain of its affiliates and principals, “Wexford”). Wexford Capital is an SEC registered investment advisor which was formed in 1994 and manages a series of investment funds and has approximately $3.5 billion of assets under management. Since the formation of our predecessor, we have significantly grown our coal reserves. Since April 2003, we have completed numerous coal asset acquisitions with a total purchase price of approximately $357.5 million. Through these acquisitions and coal lease transactions, we have substantially increased our proven and probable coal reserves and non-reserve coal deposits. In addition, we have successfully grown our production through internal development projects.

We were formed in April 2010 to own and control the coal properties and related assets owned by Rhino Energy LLC. On October 5, 2010, we completed our IPO, in which we sold an aggregate of 3,730,600 common units to the public. Our common units are listed on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “RNO”. In connection with the IPO, Wexford contributed their membership interests in Rhino Energy LLC to us, and we issued 12,397,000 subordinated units representing limited partner interests in us and 8,666,400 common units to Wexford and issued incentive distribution rights to our general partner. Principals of Wexford Capital, including certain directors of our general partner, own the majority of the membership interests in our general partner.

| 7 |

In May 2012, we completed the purchase of certain rights to coal leases and surface property located in Daviess and McLean counties in western Kentucky. These coal leases and property are estimated to contain approximately 32.4 million tons of proven and probable coal reserves that are contiguous to the Green River. The property is fully permitted and provides us with access to Illinois Basin coal that is adjacent to a navigable waterway, which could allow for exports to non-U.S. customers. During 2014, we completed the initial construction of a new underground mining operation on this property. Production began in late May 2014 and the first barge shipments of coal departed from this facility in early July 2014. We have a long-term sales contract with an electric utility anchor customer and we have conducted many test shipments to potential customers that we believe could lead to additional long-term sales agreements. In addition, in June 2011 we completed the acquisition of 100% of the ownership interests in The Elk Horn Coal Company (“Elk Horn”) for approximately $119.7 million in cash consideration. Elk Horn is primarily a coal leasing company located in eastern Kentucky that provides us with coal royalty revenues, which we believe helps to diversify our income stream while limiting our direct operational risk.

We are managed by the board of directors and executive officers of our general partner. Our operations are conducted through, and our operating assets are owned by, our wholly owned subsidiary, Rhino Energy LLC, and its subsidiaries.

Coal Operations

Mining and Leasing Operations

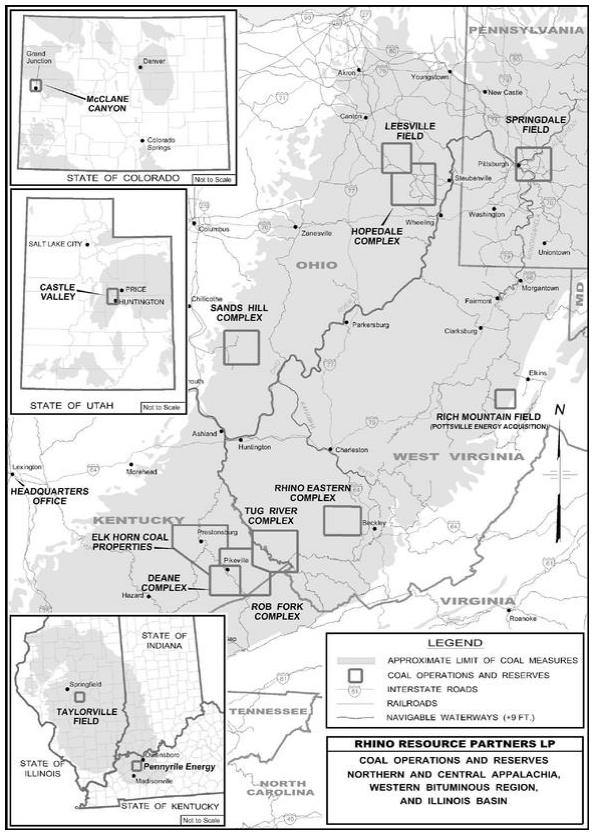

As of December 31, 2014, we operated three mining complexes located in Central Appalachia (Tug River, Rob Fork and Deane) along with our Elk Horn coal leasing operations in Central Appalachia. In addition, we operated two mining complexes located in Northern Appalachia (Hopedale and Sands Hill). In the Western Bituminous region, we operated one mining complex located in Emery and Carbon Counties, Utah (Castle Valley). We also had one underground mine located in the Western Bituminous region in Colorado (McClane Canyon) that was permanently idled at the end of 2013 (see Note 6 of the consolidated financial statements included elsewhere in this annual report for further information). During 2014, we developed a new mining complex in the Illinois Basin, our Riveredge mine at our Pennyrile mining complex, which began production in mid-2014. The Pennyrile complex consists of one underground mine, a preparation plant and river loadout facility.

We define a mining complex as a central location for processing raw coal and loading coal into railroad cars or trucks for shipment to customers. These mining complexes include seven active preparation plants and/or loadouts, each of which receive, blend, process and ship coal that is produced from one or more of our active surface and underground mines. All of the preparation plants are modern plants that have both coarse and fine coal cleaning circuits.

The following map shows the location of our coal mining and leasing operations as of December 31, 2014 (Note: the McClane Canyon mine in Colorado was permanently idled at December 31, 2013):

| 8 |

| 9 |

Our surface mines include area mining and contour mining. These operations use truck and wheel loader equipment fleets along with large production tractors and shovels. Our underground mines utilize the room and pillar mining method. These operations generally consist of one or more single or dual continuous miner sections which are made up of the continuous miner, shuttle cars, roof bolters, feeder and other support equipment. We currently own most of the equipment utilized in our mining operations. We employ preventive maintenance and rebuild programs to ensure that our equipment is modern and well-maintained. The rebuild programs are performed either by an on-site shop or by third-party manufacturers. The mobile equipment utilized at our mining operations is scheduled for replacement on an on-going basis with new, more efficient units according to a predetermined schedule.

The following table summarizes our and the Rhino Eastern joint venture’s mining complexes and production by region as of December 31, 2014. The tons produced by the Elk Horn lessees are not included in the table below since we did not directly mine these tons, but rather collected royalty revenues from the lessees.

| Region | Preparation Plants and Loadouts | Transportation to Customers(1) | Number and Type of Active Mines(2) | Tons Produced for the Year Ended December 31, 2014(3) | ||||

| (in million tons) | ||||||||

| Central Appalachia | ||||||||

| Tug River Complex (KY, WV) | Tug Fork & Jamboree(4) | Truck, Barge, Rail (NS) | 2S | 0.5 | ||||

| Rob Fork Complex (KY) | Rob Fork | Truck, Barge, Rail (CSX) | 1U, 1S | 0.4 | ||||

| Deane Complex (KY) | Rapid Loader | Rail (CSX) | — | 0.2 | ||||

| Northern Appalachia | ||||||||

| Hopedale Complex (OH) | Nelms | Truck, Rail (OHC, WLE) | 1U | 0.8 | ||||

| Sands Hill Complex (OH) | Sands Hill(5) | Truck, Barge | 2S | 0.2 | ||||

| Illinois Basin | ||||||||

| Taylorville Field (IL) | n/a | Rail (NS) | — | — | ||||

| Pennyrile Complex (KY)(6) | Preparation plant & river loadout | Barge | 1U | 0.2 | ||||

| Western Bituminous | ||||||||

| Castle Valley Complex (UT) | Truck loadout | Truck | 1U | 1.1 | ||||

| McClane Canyon Mine (CO)(6) | n/a | Truck | — | — | ||||

| Total | 4U,5S | 3.4 | ||||||

| Central Appalachia | ||||||||

| Rhino Eastern Complex (WV)(7) | Rocklick | Truck, Rail (NS, CSX) | 1U | 0.2 |

(1) NS = Norfolk Southern Railroad; CSX = CSX Railroad; OHC = Ohio Central Railroad; WLE = Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad.

(2) Numbers indicate the number of active mines. U = underground; S = surface. All of our mines as of December 31, 2013 were company-operated.

(3) Total production based on actual amounts and not rounded amounts shown in this table.

(4) Jamboree includes only a loadout facility.

(5) Includes only a preparation plant.

(6) The McClane Canyon mine was permanently idled as of December 31, 2013.

(7) Owned by a joint venture in which we had a 51% membership interest and for which we served as manager. We dissolved the joint venture arrangement in January 2015. Amounts shown include 100% of the production.

Central Appalachia. As of December 31, 2014, we operated three mining complexes located in Central Appalachia consisting of one active underground mine and three surface mines. For the year ended December 31, 2014, the mines at our Tug River, Rob Fork and Deane mining complexes produced an aggregate of approximately 0.8 million tons of steam coal and an estimated 0.3 million tons of metallurgical coal. The underground mine at the Rhino Eastern mining complex, which was previously owned by the Rhino Eastern joint venture in which we had a 51% membership interest and for which we served as manager, produced approximately 0.2 million tons of metallurgical coal. The Rhino Eastern joint venture was dissolved in January 2015. In addition, for the year ended December 31, 2014, lessees of our Elk Horn properties produced approximately 2.9 million tons of coal.

| 10 |

Tug River Mining Complex. Our Tug River mining complex is located in Kentucky and West Virginia that borders the Tug River. This complex produces coal from two company operated surface mines, which includes one high-wall mining unit. Coal production from these operations is delivered to the Tug Fork preparation plant for processing and then transported by truck to the Jamboree rail loadout for blending and shipping. Coal suitable for direct-ship to customers is delivered by truck directly to the Jamboree rail loadout from the mine sites. The Tug Fork plant is a modern, 350 tons per hour preparation plant utilizing heavy media circuitry that is capable of cleaning coarse and fine coal size fractions. The Jamboree loadout is located on the Norfolk Southern Railroad and is a modern unit train, batch weigh loadout. This mining complex produced approximately 0.3 million tons of steam coal and approximately 0.2 million tons of metallurgical coal for the year ended December 31, 2014.

Rob Fork Mining Complex. Our Rob Fork mining complex is located in eastern Kentucky and currently produces coal from one company-operated surface mine and one company-operated underground mine. The Rob Fork mining complex is located on the CSX Railroad and consists of a modern preparation plant utilizing heavy media circuitry that is capable of cleaning coarse and fine coal size fractions and a unit train loadout with batch weighing equipment. The mining complex has significant blending capabilities allowing the blending of raw coals with washed coals to meet a wide variety of customers’ needs. The Rob Fork mining complex produced approximately 0.3 million tons of steam coal and 0.1 million tons of metallurgical coal for the year ended December 31, 2014.

Deane Mining Complex. Our Deane mining complex is located in eastern Kentucky and produced steam coal from one company-operated underground mine that was idle as of December 31, 2014. The infrastructure consists of a preparation plant utilizing heavy media circuitry capable of cleaning coarse and fine coal size fractions, as well as a unit train loadout facility with batch weighing equipment capable of loading in excess of 10,000 tons into railcars in approximately four hours. The facility has significant blending capabilities allowing the blending of raw coals with washed coals to meet a wide variety of customers’ needs. The Deane complex produced approximately 0.2 million tons of steam coal for the year ended December 31, 2014.

Rhino Eastern Mining Complex. The Rhino Eastern mining complex was previously owned through a joint venture where we had a 51% membership interest in, and served as manager for the mining complex located in Raleigh and Wyoming Counties, West Virginia. The joint venture was dissolved in January 2015 and an affiliate of Patriot, our previous joint venture partner, assumed ownership and operation of the mining operations.

The Rhino Eastern mining complex produced approximately 0.2 million tons of premium mid-vol metallurgical coal for the year ended December 31, 2014.

Elk Horn Coal Leasing. Elk Horn is primarily a coal leasing company located in eastern Kentucky that provides us with coal royalty revenues. For the year ended December 31, 2014, Elk Horn lessees produced approximately 2.9 million tons of coal from our Elk Horn properties.

Northern Appalachia. We operate two mining complexes located in Northern Appalachia consisting of one company-operated underground mine and two company-operated surface mines. For the year ended December 31, 2014, these mines produced an aggregate of approximately 1.0 million tons of steam coal.

Hopedale Mining Complex. The Hopedale mining complex includes an underground mine located in Hopedale, Ohio approximately five miles northeast of Cadiz, Ohio. Coal produced from the Hopedale mine is first cleaned at our Nelms preparation plant located on the Ohio Central Railroad and the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad and then shipped by train or truck to our customers. The infrastructure includes a full-service loadout facility. This underground mining operation produced approximately 0.8 million tons of steam coal for the year ended December 31, 2014.

| 11 |

Sands Hill Mining Complex. We currently operate two surface mines at our Sands Hill mining complex, located near Hamden, Ohio. The infrastructure includes a preparation plant along with a river front barge and dock facility on the Ohio River. The Sands Hill mining complex produced approximately 0.2 million tons of steam coal and approximately 0.4 million tons of limestone aggregate for the year ended December 31, 2014.

Western Bituminous Region. In January 2011, we began production at an underground mine in Emery and Carbon Counties, Utah. We also had one underground mine located in the Western Bituminous region in Colorado (McClane Canyon) that was permanently idled at the end of 2013 (see Note 6 of the consolidated financial statements included elsewhere in this annual report for further information).

Castle Valley Mining Complex. In August 2010, we completed the acquisition of certain mining assets of C.W. Mining Company out of bankruptcy. The assets acquired are located in Emery and Carbon Counties, Utah and include coal reserves and non-reserve coal deposits, underground mining equipment and infrastructure, an overland belt conveyor system, a loading facility and support facilities. We produced approximately 1.1 million tons of steam coal from one underground mine at this complex for the year ended December 31, 2014.

Illinois Basin. In May 2012, we completed the purchase of certain rights to coal leases and surface property that is contiguous to the Green River and located in Daviess and McLean counties in western Kentucky where we constructed a new underground mining complex.

Pennyrile Mining Complex. In mid-2014, we completed the initial construction of a new underground mining operation on the purchased property, referred to as our Pennyrile mining complex, which includes one underground mine, a preparation plant and river loadout facility. Production from this new underground mine began in mid-2014 and initial production was 0.2 million tons for the year ended December 31, 2014. We believe the possibility exists to expand production up to 2.0 million tons per year with further development of the mine at the Pennyrile complex.

Other Non-Mining Operations

In addition to our mining operations, we operate several subsidiaries which provide auxiliary services for our coal mining operations. Rhino Trucking provides our Kentucky coal operations with dependable, safe coal hauling to our preparation plants and loadout facilities and our southeastern Ohio coal operations with reliable transportation to our customers where rail is not available. Rhino Services is responsible for mine-related construction, site and roadway maintenance and post-mining reclamation. Through Rhino Services, we plan and monitor each phase of our mining projects as well as the post-mining reclamation efforts. We also perform the majority of our drilling and blasting activities at our company-operated surface mines in-house rather than contracting to a third party.

Other Natural Resource Assets

Oil and Gas

In addition to our coal operations, we have invested in oil and natural gas mineral rights and operations that we believe will help to diversify our income stream.

In September 2014, we made an initial investment of $5.0 million in a new joint venture, Sturgeon Acquisitions LLC (“Sturgeon”), with affiliates of Wexford Capital and Gulfport. Sturgeon subsequently acquired 100% of the outstanding equity interests of certain limited liability companies located in Wisconsin that provide frac sand for oil and natural gas drillers in the United States. We account for the investment in this joint venture and results of operations under the equity method. We recorded our proportionate portion of the operating gains for this investment during 2014 of approximately $0.4 million.

| 12 |

In December 2012, we made an initial investment of approximately $2.0 million in a new joint venture, Muskie Proppant LLC (“Muskie”), with affiliates of Wexford Capital. Muskie was formed to provide sand for fracking operations to drillers in the Utica Shale region and other oil and natural gas basins in the U.S. We recorded our proportionate share of the operating loss for 2014 and 2013 of approximately $0.1 million and $0.5 million, respectively. During the year ended December 31, 2014 and 2013, we contributed additional capital based upon our ownership interest to the Muskie joint venture in the amount of $0.2 million and $0.5 million, respectively. In addition, during the year ended December 31, 2013, we provided a loan based upon our ownership share to Muskie in the amount of $0.2 million, which was fully repaid in November 2014 in conjunction with our contribution of our interest in Muskie to Mammoth Energy Partners LP (“Mammoth”). In November 2014, we contributed our investment interest in Muskie to Mammoth in return for a limited partner interest in Mammoth. Mammoth was formed to own various companies that provide services to companies who engage in the exploration and development of North American onshore unconventional oil and natural gas reserves. Mammoth’s companies provide services that include completion and production services, contract land and directional drilling services and remote accommodation services.

In addition, during the second quarter of 2012 we formed a services company (“Razorback”) to provide drill pad construction services in the Utica Shale for drilling operators. Razorback has completed the construction of numerous drill pads since its inception, along with the construction of impoundments for fracking water and the construction of several access roads for operators in the Utica Shale region.

In March 2012, we made an initial investment of approximately $0.1 million in a new joint venture, Timber Wolf Terminals LLC (“Timber Wolf”), with affiliates of Wexford Capital. Timber Wolf was formed to construct and operate a condensate river terminal that will provide barge trans-loading services for parties conducting activities in the Utica Shale region of eastern Ohio. The initial investment was our proportionate minority ownership interest to purchase land for the construction site of the condensate river terminal. Timber Wolf has had no operating activities since its inception.

Limestone

Incidental to our coal mining process, we mine limestone from reserves located at our Sands Hill mining complex and sell it as aggregate to various construction companies and road builders that are located in close proximity to the mining complex when market conditions are favorable. We believe that our production of limestone provides us with an additional source of revenues at low incremental capital cost.

Coal Customers

General

Our primary customers for our steam coal are electric utilities, and the metallurgical coal we produce is sold primarily to domestic and international steel producers. Excluding results from the Rhino Eastern joint venture, for the year ended December 31, 2014, approximately 91% of our coal sales tons consisted of steam coal and approximately 9% consisted of metallurgical coal. For the year ended December 31, 2014, 100% of the Rhino Eastern joint venture’s coal sales tons consisted of metallurgical coal. For the year ended December 31, 2014, excluding results from the Rhino Eastern joint venture, approximately 81% of our coal sales tons that we produced were sold to electric utilities. The majority of our electric utility customers purchase coal for terms of one to three years, but we also supply coal on a spot basis for some of our customers. Excluding the results from the Rhino Eastern joint venture, for the year ended December 31, 2014, we derived approximately 81.0% of our total coal revenues from sales to our ten largest customers, with affiliates of our top three customers accounting for approximately 39.2% of our coal revenues for that period: NRG Energy, Inc. (fka GenOn Energy, Inc.) (15.6%); PPL Corporation (12.1%); and Intermountain Power Agency (11.5%). Additionally, pursuant to the terms of a coal purchase agreement entered into under the previous Rhino Eastern joint venture agreement, we sold 100% of Rhino Eastern’s production to an affiliate of our joint venture partner, Patriot, which controlled the amount and terms of sales of the coal produced from Rhino Eastern. As discussed earlier, the Rhino Eastern joint venture was dissolved in January 2015. Incidental to our coal mining process, we mine limestone and sell it as aggregate to various construction companies and road builders that are located in close proximity to our Sands Hill mining complex.

| 13 |

Coal Supply Contracts

For each of the years ended December 31, 2014 and 2013, approximately 78% and 88%, respectively, of our aggregate coal tons sold were sold through supply contracts. We expect to continue selling a significant portion of our coal under supply contracts. As of December 31, 2014, we had commitments under supply contracts to deliver annually scheduled base quantities as follows:

| Year | Tons (in thousands) | Number of customers | ||

| 2015 | 3,260 | 13 | ||

| 2016 | 2,121 | 5 | ||

| 2017 | 1,100 | 2 |

Some of the contracts have sales price adjustment provisions, subject to certain limitations and adjustments, based on a variety of factors and indices.

Quality and volumes for the coal are stipulated in coal supply contracts, and in some instances buyers have the option to vary annual or monthly volumes. Most of our coal supply contracts contain provisions requiring us to deliver coal within certain ranges for specific coal characteristics such as heat content, sulfur, ash, hardness and ash fusion temperature. Failure to meet these specifications can result in economic penalties, suspension or cancellation of shipments or termination of the contracts. Some of our contracts specify approved locations from which coal may be sourced. Some of our contracts set out mechanisms for temporary reductions or delays in coal volumes in the event of a force majeure, including events such as strikes, adverse mining conditions, mine closures, or serious transportation problems that affect us or unanticipated plant outages that may affect the buyers.

The terms of our coal supply contracts result from competitive bidding procedures and extensive negotiations with customers. As a result, the terms of these contracts, including price adjustment features, price re-opener terms, coal quality requirements, quantity parameters, permitted sources of supply, future regulatory changes, extension options, force majeure, termination and assignment provisions, vary significantly by customer.

Coal Lease Agreements

With respect to our coal leasing operations, we enter into leases with coal mine operators granting them the right to mine and sell coal from our Elk Horn properties in exchange for a royalty payment. Generally, the lease terms provide us with a royalty fee of 6% to 9% of the gross sales price of the coal, with a minimum royalty fee ranging from $1.85 to $4.75 per ton. The terms of such leases vary from five years to the life of the reserves. A minimum royalty is required annually or monthly whether or not the property is mined.

Transportation

We ship coal to our customers by rail, truck or barge. For the year ended December 31, 2014, the majority of our coal sales tonnage was shipped by rail. The majority of our coal is transported to customers by either the CSX Railroad or the Norfolk Southern Railroad in eastern Kentucky and by the Ohio Central Railroad or the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad in Ohio. In addition, in southeastern Ohio, we use our own trucking operations to transport coal to our customers where rail is not available. We use third-party trucking to transport coal to our customers in Utah. For our new Pennyrile complex in western Kentucky, coal is transported to our customers via barge from our river loadout on the Green River located on our Pennyrile mining complex. In addition, coal from certain of our Central Appalachia and southern Ohio mines is located within economical trucking distance to the Big Sandy River and/or the Ohio River and can be transported by barge. It is customary for customers to pay the transportation costs to their location.

We believe that we have good relationships with rail carriers and truck companies due, in part, to our modern coal-loading facilities at our loadouts and the working relationships and experience of our transportation and distribution employees.

| 14 |

Suppliers

Principal supplies used in our business include diesel fuel, explosives, maintenance and repair parts and services, roof control and support items, tires, conveyance structures, ventilation supplies and lubricants. We use third-party suppliers for a significant portion of our equipment rebuilds and repairs, drilling services and construction.

We have a centralized sourcing group for major supplier contract negotiation and administration, for the negotiation and purchase of major capital goods and to support the mining and coal preparation plants. We are not dependent on any one supplier in any region. We promote competition between suppliers and seek to develop relationships with those suppliers whose focus is on lowering our costs. We seek suppliers who identify and concentrate on implementing continuous improvement opportunities within their area of expertise.

Competition

The coal industry is highly competitive. There are numerous large and small producers in all coal producing regions of the United States and we compete with many of these producers. Our main competitors include Alliance Resource Partners LP, Alpha Natural Resources, Inc., Arch Coal, Inc., Booth Energy Group, CONSOL Energy Inc., Murray Energy Corporation, Foresight Energy LP, Westmoreland Resource Partners, LP, Patriot and Bowie Resource Partners LLC.

The most important factors on which we compete are coal price, coal quality and characteristics, transportation costs and the reliability of supply. Demand for coal and the prices that we will be able to obtain for our coal are closely linked to coal consumption patterns of the domestic electric generation industry and international consumers. These coal consumption patterns are influenced by factors beyond our control, including demand for electricity, which is significantly dependent upon economic activity and summer and winter temperatures in the United States, government regulation, technological developments and the location, availability, quality and price of competing sources of fuel such as natural gas, oil and nuclear, and alternative energy sources such as hydroelectric power and wind power.

Regulation and Laws

Our operations are subject to regulation by federal, state and local authorities on matters such as:

| ● | employee health and safety; |

| ● | mine permits and other licensing requirements; |

| ● | air quality standards; |

| ● | water quality standards; |

| ● | storage, treatment, use and disposal of petroleum products and other hazardous substances; |

| ● | plant and wildlife protection; |

| ● | reclamation and restoration of mining properties after mining is completed; |

| ● | the discharge of materials into the environment, including waterways or wetlands; |

| ● | storage and handling of explosives; |

| ● | wetlands protection; |

| ● | surface subsidence from underground mining; |

| ● | the effects, if any, that mining has on groundwater quality and availability; and |

| ● | legislatively mandated benefits for current and retired coal miners. |

| 15 |

In addition, many of our customers are subject to extensive regulation regarding the environmental impacts associated with the combustion or other use of coal, which could affect demand for our coal. The possibility exists that new laws or regulations, or new interpretations of existing laws or regulations, may be adopted that may have a significant impact on our mining operations, oil and natural gas investments, or our customers’ ability to use coal.

We are committed to conducting mining operations in compliance with applicable federal, state and local laws and regulations. However, because of extensive and comprehensive regulatory requirements, violations during mining operations occur from time to time. Violations, including violations of any permit or approval, can result in substantial civil and in severe cases, criminal fines and penalties, including revocation or suspension of mining permits. None of the violations to date have had a material impact on our operations or financial condition.

While it is not possible to quantify the costs of compliance with applicable federal and state laws and regulations, those costs have been and are expected to continue to be significant. Nonetheless, capital expenditures for environmental matters have not been material in recent years. We have accrued for the present value of estimated cost of reclamation and mine closings, including the cost of treating mine water discharge when necessary. The accruals for reclamation and mine closing costs are based upon permit requirements and the costs and timing of reclamation and mine closing procedures. Although management believes it has made adequate provisions for all expected reclamation and other costs associated with mine closures, future operating results would be adversely affected if we later determined these accruals to be insufficient. Compliance with these laws and regulations has substantially increased the cost of coal mining for all domestic coal producers. Most of the statutes discussed below apply to exploration and development activities associated with our oil and natural gas investments as well, and therefore we do not present a separate discussion of statutes related to those activities.

Mining Permits and Approvals

Numerous governmental permits or approvals are required for coal mining operations. When we apply for these permits and approvals, we are often required to assess the effect or impact that any proposed production of coal may have upon the environment. The permit application requirements may be costly and time consuming, and may delay or prevent commencement or continuation of mining operations in certain locations. Future laws and regulations may emphasize more heavily the protection of the environment and, as a consequence, our activities may be more closely regulated. Laws and regulations, as well as future interpretations or enforcement of existing laws and regulations, may require substantial increases in equipment and operating costs, or delays, interruptions or terminations of operations, the extent of any of which cannot be predicted. The permitting process for certain mining operations can extend over several years, and can be subject to judicial challenge, including by the public. Some required mining permits are becoming increasingly difficult to obtain in a timely manner, or at all. We may experience difficulty and/or delay in obtaining mining permits in the future.

Regulations provide that a mining permit can be refused or revoked if the permit applicant or permittee owns or controls, directly or indirectly through other entities, mining operations which have outstanding environmental violations. Although, like other coal companies, we have been cited for violations in the ordinary course of business, we have never had a permit suspended or revoked because of any violation, and the penalties assessed for these violations have not been material.

Before commencing mining on a particular property, we must obtain mining permits and approvals by state regulatory authorities of a reclamation plan for restoring, upon the completion of mining, the mined property to its approximate prior condition, productive use or other permitted condition.

| 16 |

Mine Health and Safety Laws

Stringent safety and health standards have been in effect since the adoption of the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969. The Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977 (the “Mine Act”), and regulations adopted pursuant thereto, significantly expanded the enforcement of health and safety standards and imposed comprehensive safety and health standards on numerous aspects of mining operations, including training of mine personnel, mining procedures, blasting, the equipment used in mining operations and other matters. The Mine Safety and Health Administration (“MSHA”) monitors compliance with these laws and regulations. In addition, the states where we operate also have state programs for mine safety and health regulation and enforcement. Federal and state safety and health regulations affecting the coal industry are complex, rigorous and comprehensive, and have a significant effect on our operating costs.

The Mine Act is a strict liability statute that requires mandatory inspections of surface and underground coal mines and requires the issuance of enforcement action when it is believed that a standard has been violated. A penalty is required to be imposed for each cited violation. Negligence and gravity assessments result in a cumulative enforcement scheme that may result in the issuance of an order requiring the immediate withdrawal of miners from the mine or shutting down a mine or any section of a mine or any piece of mine equipment. The Mine Act contains criminal liability provisions. For example, criminal liability may be imposed for corporate operators who knowingly or willfully authorize, order or carry out violations. The Mine Act also provides that civil and criminal penalties may be assessed against individual agents, officers and directors who knowingly authorize, order or carry out violations.

We have developed a health and safety management system that, among other things, educates our employees about health and safety requirements including those arising under federal and state laws that apply to our mines. In addition, our health and safety management system tracks the performance of each operational facility in meeting the requirements of safety laws and company safety policies. As an example of the resources we allocate to health and safety matters, our safety management system includes a company-wide safety director and local safety directors who oversee safety and compliance at operations on a day-to-day basis. We continually monitor the performance of our safety management system and from time-to-time modify that system to address findings or reflect new requirements or for other reasons. We have even integrated safety matters into our compensation and retention decisions. For instance, our bonus program includes a meaningful evaluation of each eligible employee’s role in complying with, fostering and furthering our safety policies.

We evaluate a variety of safety-related metrics to assess the adequacy and performance of our safety management system. For example, we monitor and track performance in areas such as “accidents, reportable accidents, lost time accidents and the lost-time accident frequency rate” and a number of others. Each of these metrics provides insights and perspectives into various aspects of our safety systems and performance at particular locations or mines generally and, among other things, can indicate where improvements are needed or further evaluation is warranted with regard to the system or its implementation. An important part of this evaluation is to assess our performance relative to certain national benchmarks.

Our non-fatal days lost time incidence rate for all operations for the year ended December 31, 2014 was 1.63 as compared to the most recent national average of 2.42, as reported by MSHA, or 32.76% below this national average. Non-fatal days lost incidence rate is an industry standard used to describe occupational injuries that result in loss of one or more days from an employee’s scheduled work. In addition, for the year ended December 31, 2014 our average MSHA violations per inspection day was 0.46 as compared to the most recent national average of 0.62 violations per inspection day for coal mining activity as reported by MSHA, or 25.80% below this national average.

Mining accidents in the last several years in West Virginia, Kentucky and Utah have received national attention and instigated responses at the state and national levels that have resulted in increased scrutiny of current safety practices and procedures at all mining operations, particularly underground mining operations. More stringent mine safety laws and regulations promulgated by these states and the federal government have included increased sanctions for non-compliance. For example, in 2006, the Mine Improvement and New Emergency Response Act of 2006, or MINER Act, was enacted. The MINER Act significantly amended the Mine Act, requiring improvements in mine safety practices, increasing criminal penalties and establishing a maximum civil penalty for non-compliance, and expanding the scope of federal oversight, inspection and enforcement activities. Since passage of the MINER Act, enforcement scrutiny has increased, including more inspection hours at mine sites, increased numbers of inspections and increased issuance of the number and the severity of enforcement actions and related penalties. Other states have proposed or passed similar bills, resolutions or regulations addressing mine safety practices. Moreover, workplace accidents, such as the April 5, 2010, Upper Big Branch Mine incident, have resulted in more inspection hours at mine sites, increased number of inspections and increased issuance of the number and severity of enforcement actions and the passage of new laws and regulations. These trends are likely to continue.

| 17 |

Indeed, in 2013, MSHA began implementing its recently released Pattern of Violation (“POV”) regulations under the Mine Act. Under this regulation, MSHA eliminated the ninety (90) day window to take corrective action and engage in mitigation efforts for mine operators who met certain initial POV screening criteria. Additionally, MSHA will make POV determinations based upon enforcement actions as issued, rather than enforcement actions that have been rendered final following the opportunity for administrative or judicial review. After a mine operator has been placed on POV status, MSHA will thereafter issue an order withdrawing miners from the area affected by any enforcement action designated by MSHA as posing a significant and substantial, or S&S, hazard to the health and/or safety of miners. Further, once designated as a POV mine, a mine operator can be removed from POV status only upon: (1) a complete inspection of the entire mine with no S&S enforcement actions issued by MSHA; or (2) no POV-related withdrawal orders being issued by MSHA within ninety (90) days of the mine operator being placed on POV status. Although it remains to be seen how these new regulations will ultimately affect production at our mines, they are consistent with the trend of more stringent enforcement.

From time to time, certain portions of individual mines have been required to suspend or shut down operations temporarily in order to address a compliance requirement or because of an accident. For instance, MSHA issues orders pursuant to Section 103(k) that, among other things, call for operations in the area of the mine at issue to suspend operations until compliance is restored. Likewise, if an accident occurs within a mine, the MSHA requirements call for all operations in that area to be suspended until the circumstance leading to the accident has been resolved. During the fiscal year ended December 31, 2014 (as in earlier years), we received such orders from government agencies and have experienced accidents within our mines requiring the suspension or shutdown of operations in those particular areas until the circumstances leading to the accident have been resolved. While the violations or other circumstances that caused such an accident were being addressed, other areas of the mine could and did remain operational. These circumstances did not require us to suspend operations on a mine-wide level or otherwise entail material financial or operational consequences for us. Any suspension of operations at any one of our locations that may occur in the future may have material financial or operational consequences for us.

It is our practice to contest notices of violations in cases in which we believe we have a good faith defense to the alleged violation or the proposed penalty and/or other legitimate grounds to challenge the alleged violation or the proposed penalty. In December 2008 and March 2009, MSHA assessed proposed penalties in excess of $100,000 with regard to three separate notices of violation, all of which relate to our operations at Mine 28. Each of these notices of violation alleged an “unwarrantable failure” under the Mine Act with specific regard to the accumulation of combustible materials. The combustible materials typically underlying such citations are coal, loose coal, and float coal dust. We have contested these violations on grounds that the underlying circumstances did not support the issuance of a notice of violation and/or the gravity of the proposed penalty. These contests are still pending and we cannot predict the outcome of these proceedings or assure you that the fines and penalties will not be assessed in full against us. These alleged violations were abated at the time or immediately after the notices of violation were issued, and we have not been issued any notices of violation from MSHA proposing a penalty in excess of $100,000 since March 2009.

We exercise substantial efforts toward achieving compliance at our mines. In light of the recent citations issued with respect to our mines, we have further increased our focus with regard to health and safety at all of our mines and at Mine 28 and Eagle #1 Mine in particular. These efforts include hiring additional skilled personnel, providing training programs, hosting quarterly safety meetings with MSHA personnel and making capital expenditures in consultation with MSHA aimed at increasing mine safety. We believe that these efforts have contributed, and continue to contribute, positively to safety and compliance at our mines. In Item 4. Mine Safety Disclosure and in Exhibit 95 to this Annual Report on Form 10-K, we provide additional details on how we monitor safety performance and MSHA compliance, as well as provide the mine safety disclosures required pursuant to Section 1503(a) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.

| 18 |

Black Lung Laws

Under the Black Lung Benefits Act of 1977 and the Black Lung Benefits Reform Act of 1977, as amended in 1981, coal mine operators must make payments of black lung benefits to current and former coal miners with black lung disease, some survivors of a miner who dies from this disease, and to fund a trust fund for the payment of benefits and medical expenses to claimants who last worked in the industry prior to January 1, 1970. To help fund these benefits, a tax is levied on production of $1.10 per ton for underground-mined coal and $0.55 per ton for surface-mined coal, but not to exceed 4.4% of the applicable sales price. This excise tax does not apply to coal that is exported outside of the United States. In 2014, we recorded approximately $3.0 million of expense related to this excise tax.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act includes significant changes to the federal black lung program including an automatic survivor benefit paid upon the death of a miner with an awarded black lung claim and establishes a rebuttable presumption with regard to pneumoconiosis among miners with 15 or more years of coal mine employment that are totally disabled by a respiratory condition. These changes could have a material impact on our costs expended in association with the federal black lung program. We may also be liable under state laws for black lung claims that are covered through either insurance policies or state programs.

Workers’ Compensation

We are required to compensate employees for work-related injuries under various state workers’ compensation laws. The states in which we operate consider changes in workers’ compensation laws from time to time. Our costs will vary based on the number of accidents that occur at our mines and other facilities, and our costs of addressing these claims. We are insured under the Ohio State Workers Compensation Program for our operations in Ohio. Our remaining operations, including Central Appalachia and the Western Bituminous region, are insured through Rockwood Casualty Insurance Company.

Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (“SMCRA”)

SMCRA establishes operational, reclamation and closure standards for all aspects of surface mining, including the surface effects of underground coal mining. SMCRA requires that comprehensive environmental protection and reclamation standards be met during the course of and upon completion of mining activities. In conjunction with mining the property, we reclaim and restore the mined areas by grading, shaping and preparing the soil for seeding. Upon completion of mining, reclamation generally is completed by seeding with grasses or planting trees for a variety of uses, as specified in the approved reclamation plan. We believe we are in compliance in all material respects with applicable regulations relating to reclamation.

SMCRA and similar state statutes require, among other things, that mined property be restored in accordance with specified standards and approved reclamation plans. The act requires that we restore the surface to approximate the original contours as soon as practicable upon the completion of surface mining operations. The mine operator must submit a bond or otherwise secure the performance of these reclamation obligations. Mine operators can also be responsible for replacing certain water supplies damaged by mining operations and repairing or compensating for damage to certain structures occurring on the surface as a result of mine subsidence, a consequence of long-wall mining and possibly other mining operations. In addition, the Abandoned Mine Lands Program, which is part of SMCRA, imposes a tax on all current mining operations, the proceeds of which are used to restore mines closed prior to SMCRA’s adoption in 1977. The maximum tax for the period from October 1, 2012 through September 30, 2021, has been decreased to 28 cents per ton on surface mined coal and 12 cents per ton on underground mined coal. As of December 31, 2014, we had accrued approximately $29.9 million for the estimated costs of reclamation and mine closing, including the cost of treating mine water discharge when necessary. In addition, states from time to time have increased and may continue to increase their fees and taxes to fund reclamation of orphaned mine sites and abandoned mine drainage control on a statewide basis.

After a mine application is submitted, public notice or advertisement of the proposed permit action is required, which is followed by a public comment period. It is not uncommon for a SMCRA mine permit application to take over two years to prepare and review, depending on the size and complexity of the mine, and another two years or even longer for the permit to be issued. The variability in time frame required to prepare the application and issue the permit can be attributed primarily to the various regulatory authorities’ discretion in the handling of comments and objections relating to the project received from the general public and other agencies. Also, it is not uncommon for a permit to be delayed as a result of judicial challenges related to the specific permit or another related company’s permit.

| 19 |

Federal laws and regulations also provide that a mining permit or modification can be delayed, refused or revoked if owners of specific percentages of ownership interests or controllers (i.e., officers and directors or other entities) of the applicant have, or are affiliated with another entity that has outstanding violations of SMCRA or state or tribal programs authorized by SMCRA. This condition is often referred to as being “permit blocked” under the federal Applicant Violator Systems, or AVS. Thus, non-compliance with SMCRA can provide the bases to deny the issuance of new mining permits or modifications of existing mining permits, although we know of no basis by which we would be (and we are not now) permit-blocked.

In addition, a February 2014 decision by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia invalidated the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement’s (“OSM”) 2008 Stream Buffer Zone Rule, which prohibited mining disturbances within 100 feet of streams, subject to various exemptions. In December 2014, OSM reinstated the 1983 version of the Stream Buffer Zone regulations, which offer fewer exemptions to the 100 foot buffer requirement, as a direct final rule. In 2009, OSM published an advance notice of proposed rulemaking to revise the Stream Buffer Zone Rule through a more protective regulatory strategy called the Stream Protection Rule, which would prohibit mining disturbances within 100 feet of streams if there would be a negative effect on water quality. The Stream Protection Rule has not yet been proposed or finalized. OSM is currently developing an environmental impact statement (“EIS”) for use in drafting the anticipated Stream Protection Rule. A notice of proposed rulemaking for the Stream Protection Rule is expected to be issued in April 2015. We are unable to predict the impact, if any, of these actions by the OSM, although the actions potentially could result in additional delays and costs associated with obtaining permits, prohibitions or restrictions relating to mining activities near streams, and additional enforcement actions. In addition, Congress has proposed, and may in the future propose, legislation to restrict the placement of mining material in streams. The requirements of the new Stream Protection Rule or future legislation, when adopted, will likely be stricter than the prior Stream Buffer Zone Rule to further protect streams from the impact of surface mining, and may adversely affect our business and operations.

Surety Bonds

Federal and state laws require a mine operator to secure the performance of its reclamation obligations required under SMCRA through the use of surety bonds or other approved forms of performance security to cover the costs the state would incur if the mine operator were unable to fulfill its obligations. It has become increasingly difficult for mining companies to secure new surety bonds without the posting of partial collateral. In addition, surety bond costs have increased while the market terms of surety bonds have generally become less favorable. It is possible that surety bonds issuers may refuse to renew bonds or may demand additional collateral upon those renewals. Our failure to maintain, or inability to acquire, surety bonds that are required by state and federal laws would have a material adverse effect on our ability to produce coal, which could affect our profitability and cash flow.

As of December 31, 2014, we had approximately $70.2 million in surety bonds outstanding to secure the performance of our reclamation obligations. We may be required to increase these amounts as a result of recent developments in West Virginia and Kentucky. In 2011, West Virginia passed legislation that provides for a minimum incremental bonding rate in lieu of a minimum bond amount that applies regardless of acreage. In addition, the Kentucky Department for Natural Resources and the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement Lexington Field Office executed an Action Plan for Improving the Adequacy of Kentucky Performance Bond Amounts, which provides for, among other things, revised bond computation protocols.

| 20 |

Air Emissions

The federal Clean Air Act, or the CAA, and similar state and local laws and regulations, which regulate emissions into the air, affect coal mining operations both directly and indirectly. The CAA directly impacts our coal mining and processing operations by imposing permitting requirements and, in some cases, requirements to install certain emissions control equipment, on sources that emit various hazardous and non-hazardous air pollutants. The CAA also indirectly affects coal mining operations by extensively regulating the air emissions of coal-fired electric power generating plants and other industrial consumers of coal, including air emissions of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulates, mercury and other compounds. There have been a series of recent federal rulemakings that are focused on emissions from coal-fired electric generating facilities. Installation of additional emissions control technology and additional measures required under laws and regulations related to air emissions will make it more costly to operate coal-fired power plants and possibly other facilities that consume coal and, depending on the requirements of individual state implementation plans, or SIPs, could make coal a less attractive fuel alternative in the planning and building of power plants in the future.

In addition to the greenhouse gas (“GHG”) regulations discussed below, air emission control programs that affect our operations, directly or indirectly, include, but are not limited to, the following:

| ● | The EPA’s Acid Rain Program, provided in Title IV of the CAA, regulates emissions of sulfur dioxide from electric generating facilities. Sulfur dioxide is a by-product of coal combustion. Affected facilities purchase or are otherwise allocated sulfur dioxide emissions allowances, which must be surrendered annually in an amount equal to a facility’s sulfur dioxide emissions in that year. Affected facilities may sell or trade excess allowances to other facilities that require additional allowances to offset their sulfur dioxide emissions. In addition to purchasing or trading for additional sulfur dioxide allowances, affected power facilities can satisfy the requirements of the EPA’s Acid Rain Program by switching to lower sulfur fuels, installing pollution control devices such as flue gas desulfurization systems, or “scrubbers,” or by reducing electricity generating levels. | |

| ● | The EPA has promulgated rules, referred to as the “NOx SIP Call,” that require coal-fired power plants in 22 eastern states and Washington D.C. to make substantial reductions in nitrogen oxide emissions in an effort to reduce the impacts of ozone transport between states. As a result of the program, many power plants have been or will be required to install additional emission control measures, such as selective catalytic reduction devices. | |

| ● | Additionally, in March 2005, EPA issued the final Clean Air Interstate Rule, or CAIR, which would have reduced nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emissions in 28 eastern states and Washington, D.C. pursuant to a cap and trade program similar to the system now in effect for acid rain. A December 2008 court decision found flaws in CAIR, but kept CAIR requirements in place temporarily while directing the EPA to issue a replacement rule. | |

| ● | In July 2011, EPA finalized a rule intended to replace CAIR called the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, or CSAPR, which requires 28 states in the eastern half of the US to reduce power plant emissions that cross state lines and contribute to ground-level ozone and fine particle pollution in other states. CSAPR was scheduled to replace CAIR starting January 2012. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit vacated CSAPR in August 2012, in a 2 to 1 decision, concluding that the rule was beyond the EPA’s statutory authority. The EPA petitioned for en banc review of that decision by the entire U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, but the petition was denied in January 2013. The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari and in April 2014, the Court found that the EPA was complying with statutory requirements when it issued CSAPR and reversed the D.C. Circuit’s vacation of CSAPR. Based on further proceedings in the lower court, in November 2014, EPA issued an interim final rule reconciling the CSAPR rule with the court’s order, which calls for Phase 1 implementation in 2015 and Phase 2 implementation in 2017. However, other legal challenges to CSAPR remain to be heard in the D.C. Circuit litigation, which are still pending. For states to meet their requirements under CSAPR, a number of coal-fired power plants will likely need to be retired, rather than be retrofitted with the necessary emission control technologies, reducing the demand for steam coal. |

| 21 |

| ● | In February 2012, the EPA formally adopted its “MATS rule,” which imposes a new suite of limits on coal- and oil-fired electric generating unit (“EGU”) emissions of mercury, other metals, acid gases, and organic air toxics. On July 20, 2012, the EPA announced that it is reviewing technical information that is focused on pollution limits under the MATS rule, based on new information provided by industry stakeholders after the rule was finalized. In March 2013, EPA finalized the MATS rule for new power plants, principally adjusting emissions limits to levels attainable by existing control technologies. The D.C. Circuit upheld various portions of the rulemaking in two separate decisions issued in March and April 2014, respectively. In November 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari to review the D.C. Circuit decision. These requirements could significantly increase our customers’ costs and cause them to reduce their demand for coal, which may materially impact our results or operations. Some utilities have been moving forward with installation of equipment necessary to comply with MATS, and the EPA and states have been granting additional time beyond the 2015 deadline (but no more than one extra year) for facilities that need more time to upgrade and complete those installations. The rule could result in the retirement of certain older coal plants. | |

| ● | In addition, in January 2013, the EPA issued final MACT standards for several classes of boilers and process heaters, including large coal-fired boilers and process heaters (Boiler MACT), which require significant reductions in the emission of particulate matter, carbon monoxide, hydrogen chloride, dioxins and mercury. Like MATS, Boiler MACT imposes stricter limitations on mercury emissions than those vacated in CAMR. Business and environmental groups have filed legal challenges in federal appeals court and have petitioned EPA to reconsider the rule. EPA has granted petitions for reconsideration for certain issues and published its reconsideration, which seeks additional public comment, in December 2014. However, if Boiler MACT is upheld as previously finalized, EPA estimates the rule will affect 1,700 existing major source facilities with an estimated 14,316 boilers and process heaters. Some owners will make capital expenditures to retrofit boilers and process heaters, while a number of boilers and process heaters will be prematurely retired. The retirements are likely to reduce the demand for coal. The impact of the regulations will depend on the outcome of these legal challenges and cannot be determined at this time. | |

| ● | The EPA has adopted new, more stringent national air quality standards, or NAAQS, for ozone, fine particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide. As a result, some states will be required to amend their existing SIPs to attain and maintain compliance with the new air quality standards. For example, in June 2010, the EPA issued a final rule setting forth a more stringent primary NAAQS applicable to sulfur dioxide. The rule also modifies the monitoring increment for the sulfur dioxide standard, establishing a 1-hour standard, and expands the sulfur dioxide monitoring network. Initial non-attainment determinations related to the 2010 sulfur dioxide rule were published in August 2013 with an effective date in October 2013. Determinations on remaining areas of the U.S. have to be made. States with non-attainment areas will have until April 2015 to submit SIP revisions which must meet the modified standard by summer 2017. For all other areas, states will be required to submit “maintenance” SIPs. EPA finalized its PM2.5 NAAQS designations in December 2014, although EPA deferred making designations for several areas due to data validity issues. Individual states must now identify the sources of PM2.5 emissions and develop emission reduction plans, which may be state-specific or regional in scope. Nonattainment areas must meet the revised standard no later than 2021. In November 2014, EPA also proposed a revision of the existing NAAQS for ozone, making it more stringent. Significant additional emissions control expenditures will likely be required at coal-fired power plants and coke plants to meet the new standards, which are expected to be finalized in 2015. Nitrogen oxides, which are a by-product of coal combustion, can lead to the creation of ozone. Because coal mining operations and coal-fired electric generating facilities emit particulate matter and sulfur dioxide, our mining operations and customers could be affected when the standards are implemented by the applicable states. | |