Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| EXCEL - IDEA: XBRL DOCUMENT - Green Plains Inc. | Financial_Report.xls |

| EX-23.1 - EX-23.1 - Green Plains Inc. | gpre-20141231ex231e5bf97.htm |

| EX-31.2 - EX-31.2 - Green Plains Inc. | gpre-20141231ex31282c5f3.htm |

| EX-32.1 - EX-32.1 - Green Plains Inc. | gpre-20141231ex321313e7b.htm |

| EX-31.1 - EX-31.1 - Green Plains Inc. | gpre-20141231ex311159b57.htm |

| EX-21.1 - EX-21.1 - Green Plains Inc. | gpre-20141231ex21188b912.htm |

| EX-32.2 - EX-32.2 - Green Plains Inc. | gpre-20141231ex322755b1b.htm |

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 10-K

☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2014

or

☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

For the transition period from ____ to _____

Commission file number 001-32924

Green Plains Inc.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

|

Iowa |

84-1652107 |

|

(State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) |

(I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) |

|

|

|

|

450 Regency Parkway, Suite 400, Omaha, NE 68114 |

(402) 884-8700 |

|

(Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) |

(Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Common Stock, $.001 par value

Name of exchanges on which registered: NASDAQ Stock Market

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act.

Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act.

Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files).

Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. ☒.

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer or a smaller reporting company. See definition of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer” and “smaller reporting company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

Large accelerated filer ☒. Accelerated filer ☐. Non-accelerated filer ☐ Smaller reporting company ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Act). Yes ☐ No ☒

The aggregate market value of the Company’s voting common stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant as of June 30, 2014 (the last business day of the second quarter), based on the last sale price of the common stock on that date of $32.87, was approximately $1.1 billion. For purposes of this calculation, executive officers, directors and holders of 10% or more of the registrant’s common stock are deemed to be affiliates of the registrant.

As of February 5, 2015, there were 37,608,982 shares of the registrant’s common stock outstanding.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the registrant’s definitive Proxy Statement for the 2015 Annual Meeting of Shareholders are incorporated by reference in Part III herein. The Company intends to file such Proxy Statement with the Securities and Exchange Commission no later than 120 days after the end of the period covered by this report on Form 10-K.

|

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

|

|

Page |

|

|

PART I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 1. |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 1A. |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 1B. |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 2. |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 3. |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 4. |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART II |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 5. |

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 6. |

35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 7. |

Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations. |

36 |

|

|

|

|

|

Item 7A. |

54 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 8. |

56 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 9. |

Changes in and Disagreements With Accountants on Accounting and Financial Disclosure. |

56 |

|

|

|

|

|

Item 9A. |

56 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 9B. |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART III |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 10. |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 11. |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 12. |

Security Ownership of Certain Beneficial Owners and Management and Related Stockholder Matters. |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

Item 13. |

Certain Relationships and Related Transactions, and Director Independence. |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

Item 14. |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART IV |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 15. |

60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

69 |

||

Cautionary Information Regarding Forward-Looking Statements

The Securities and Exchange Commission, or SEC, encourages companies to disclose forward-looking information so that investors can better understand a company’s future prospects and make informed investment decisions. This report contains such “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. These statements may be made directly in this report, and they may also be made a part of this report by reference to other documents filed with the SEC, which is known as “incorporation by reference.”

This report contains forward-looking statements based on current expectations that involve a number of risks and uncertainties. Forward-looking statements generally do not relate strictly to historical or current facts, but rather to plans and objectives for future operations based upon management’s reasonable estimates of future results or trends, and include statements preceded by, followed by, or that include words such as “anticipates,” “believes,” “continue,” “estimates,” “expects,” “intends,” “outlook,” “plans,” “predicts,” “may,” “could,” “should,” “will,” and words and phrases of similar impact, and include, but are not limited to, statements regarding future operating or financial performance, business strategy, business environment, key trends, and benefits of actual or planned acquisitions. In addition, any statements that refer to expectations, projections or other characterizations of future events or circumstances, including any underlying assumptions, are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements are made pursuant to safe harbor provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Although we believe that our expectations regarding future events are based on reasonable assumptions, any or all forward-looking statements in this report may turn out to be incorrect. They may be based on inaccurate assumptions or may not account for known or unknown risks and uncertainties. Consequently, no forward-looking statement is guaranteed, and actual future results may vary materially from the results expressed or implied in our forward-looking statements. The cautionary statements in this report expressly qualify all of our forward-looking statements. In addition, we are not obligated, and do not intend, to update any of our forward-looking statements at any time unless an update is required by applicable securities laws. Factors that could cause actual results to differ from those expressed or implied in the forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, those discussed in the section entitled “Risk Factors” in this report or in any document incorporated by reference. Specifically, we may experience significant fluctuations in future operating results due to a number of economic conditions, including, but not limited to, competition in the ethanol and other industries in which we operate, commodity market risks, financial market risks, counter-party risks, risks associated with changes to federal policy or regulation, risks related to closing and achieving anticipated results from acquisitions, and other risk factors detailed in our reports filed with the SEC. Actual results may differ from projected results due, but not limited, to unforeseen developments.

In light of these assumptions, risks and uncertainties, the results and events discussed in the forward-looking statements contained in this report or in any document incorporated by reference might not occur. Investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on the forward-looking statements, which speak only as of the date of this report or the date of the document incorporated by reference in this report. We are not under any obligation, and we expressly disclaim any obligation, to update or alter any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.

PART I

Item 1. Business.

Overview

References to “we,” “us,” “our,” “Green Plains,” or the “Company” in this report refer to Green Plains Inc., an Iowa corporation founded in June 2004, and its subsidiaries.

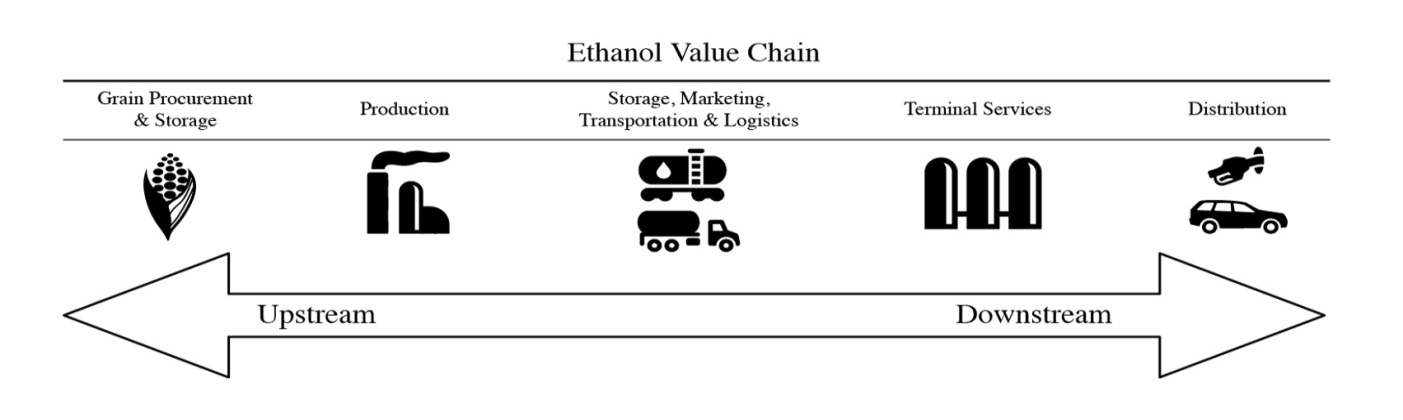

We are a Fortune 1000, vertically-integrated producer, marketer and distributor of ethanol focused on generating stable operating margins through our diversified business segments and our risk management strategy. We believe that owning and operating strategically-located assets throughout the ethanol value chain enables us to mitigate changes in commodity prices and differentiates us from companies focused only on ethanol production. We have operations throughout the ethanol value chain, beginning upstream with our grain handling and storage operations, continuing through our ethanol, distillers grains and corn oil production operations, and ending downstream with our marketing, terminal and distribution services. Following is our visual presentation of the ethanol value chain:

1

Our disciplined risk management strategy is designed to lock in operating margins by forward contracting the primary commodities involved in or derived from ethanol production: corn, natural gas, ethanol, distillers grains and corn oil. We also seek to maintain a safe environment of continuous operational improvement to increase our efficiency and effectiveness as a low-cost producer of ethanol.

We review our operations within the following four separate operating segments:

|

· |

Ethanol Production. We are North America’s fourth largest ethanol producer. We operate twelve ethanol plants in Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska and Tennessee. We have the capacity to consume approximately 360 million bushels of corn per year and produce over one billion gallons of ethanol and approximately 2.9 million tons of distillers grains annually. |

|

· |

Corn Oil Production. We operate corn oil extraction systems at our ethanol plants, with the capacity to produce approximately 250 million pounds annually. The corn oil systems are designed to extract non-edible corn oil, a value-added product, from the whole stillage immediately prior to production of distillers grains. Industrial uses for corn oil include feedstock for biodiesel, livestock feed additives, rubber substitutes, rust preventatives, inks, textiles, soaps and insecticides. |

|

· |

Agribusiness. Within our bulk grain business, we have grain storage capacity of approximately 42.2 million bushels. Our cattle feedlot operation has the capacity to support approximately 70,000 head of cattle. We believe our agribusiness operations provide synergies with our ethanol production segment as it supplies a portion of the feedstock and utilizes a portion of the distillers grains output of our ethanol plants. |

|

· |

Marketing and Distribution. Our in-house marketing business is responsible for the sale, marketing and distribution of all ethanol, distillers grains and corn oil produced at our ethanol plants. We also market and provide logistical services for ethanol and other commodities for a third-party producer. We purchase and sell ethanol, distillers grains, corn oil, grain, natural gas and other commodities and participate in other merchant trading activities in various markets. Additionally, we operate eight fuel terminals with approximately 822 million gallons per year, or mmgy, of total throughput capacity in seven south central U.S. states. To optimize the value of our assets, we utilize a portion of our leased railcar fleet to transport crude oil for third parties. |

In June 2014, we acquired the assets of a cattle-feeding business near Kismet, Kansas, which includes a feedlot and grain storage facilities. The operation, which is part of our agribusiness segment, consists of approximately 2,600 acres of land, which has the capacity to support 70,000 head of cattle, and approximately 3.8 million bushels of grain storage capacity.

In June 2013, we acquired an ethanol plant located in Atkinson, Nebraska with the capacity to produce approximately 50 mmgy. We began operations at the ethanol plant early in the third quarter of 2013. Corn oil extraction technology was installed at the plant late in the fourth quarter of 2013. Also, in June 2013, we acquired a grain elevator in Archer, Nebraska. In November 2013, we acquired two ethanol plants, located in Wood River, Nebraska and Fairmont, Minnesota, with combined annual production capacity of approximately 230 mmgy. The Fairmont, Minnesota plant, which was not operational at the time of its acquisition, began operations in January 2014 upon completion of certain maintenance and enhancement projects.

We intend to continue to take a disciplined approach in evaluating new opportunities related to potential acquisition of additional ethanol plants by considering whether the plants meet our design, engineering, valuation and geographic criteria. We believe certain expansion projects could be implemented at our ethanol plants that have the potential to utilize the

2

strategic location and capacity of these assets and cost effectively increase our annual production. In our marketing and distribution segment, our strategy is to build or acquire additional fuel terminals, expand our marketing efforts by entering into new or renewed contracts with other ethanol producers and realize additional profit margins by optimizing our commodity logistics. In 2013, we began to implement a plan to realign our agribusiness operations by adding grain storage capacity located at or near our ethanol plants to take advantage of our current infrastructure and enhance our corn origination and trading capabilities. We intend to continue to add grain storage capacity with the goal of owning approximately 50 million bushels of total storage capacity by the end of 2015. We also intend to pursue opportunities to develop or acquire additional grain elevators, specifically those located near our ethanol plants. We believe that owning additional grain handling and storage operations in close proximity to our ethanol plants enables us to strengthen relationships with local corn producers, allowing us to source corn more effectively and at a lower average cost. We will also consider acquisitions of additional cattle feedlot operations. We also own approximately 63% of BioProcess Algae LLC, which was formed to commercialize advanced photo-bioreactor technologies for growing and harvesting algal biomass.

Our Competitive Strengths

We believe we have created an efficient platform with diversified revenues and income streams. Fundamentally, we focus on managing commodity price risks, improving operating efficiencies and optimizing market opportunities. We believe our competitive strengths include:

Disciplined Risk Management. We believe risk management is a core competency of ours. Our primary focus is to lock in favorable operating margins whenever possible. We do not speculate on general price movements by taking significant unhedged positions on commodities such as corn, ethanol or natural gas. Our comprehensive risk management platform allows us to monitor real-time commodity price risk exposure at each of our plants, and to respond quickly to lock in acceptable margins or to temporarily reduce production levels at our ethanol plants during periods of compressed margins. By using a variety of risk management tools and hedging strategies, including our internally-developed real-time operating margin management system, we believe we are able to maintain a disciplined approach to risk management.

Demonstrated Acquisition and Integration Capabilities. We believe U.S. ethanol production capacity is poised for further consolidation and have demonstrated the ability to make strategic acquisitions that we believe create synergies within our vertically-integrated platform and enhance our ability to mitigate risks. Our balance sheet allows us to be opportunistic in that process. Since our inception, we have acquired or developed twelve ethanol plants in addition to upstream grain handling and storage businesses, a cattle-feeding operation and downstream terminal and distribution services. We installed corn oil extraction technology at each of our ethanol plants to generate incremental returns from this value-added product. We believe such acquisitions, developments and improvements have been successfully integrated into our business and have enhanced our overall returns.

Focus on Operational Excellence. All of our plants are staffed by experienced industry personnel. We focus on continuous incremental operational improvements to enhance overall production efficiencies, and we share operational knowledge across our plants. Using real-time production data and control systems, we continually monitor our plants in an effort to optimize performance. We believe our ability to improve operating efficiencies provides an operating cost advantage over most of our competitors. In turn, we believe we are well positioned to increase operating margins for any facilities that we may acquire in the future.

Leading Vertically-Integrated Ethanol Producer. We believe our operations throughout the ethanol value chain reduce our commodity and operating risks, and increase our pricing visibility and influence in key markets. Combined, we believe our agribusiness, ethanol production, corn oil production, and marketing and distribution segments provide efficiencies across the ethanol value chain, from grain procurement to blending fuel. Our agribusiness operations help to reduce our supply risk by providing grain handling and storage capabilities. Using our logistical capabilities and expertise, we market and distribute ethanol, distillers grains, corn oil and other commodity products. Our corn oil systems are designed to extract non-edible corn oil that has multiple industrial uses. Our fuel terminals allow us to source, store, blend and distribute ethanol and biodiesel across multiple states.

Proven Management Team. Our senior management team averages approximately 25 years of commodity risk management and related industry experience. We have specific expertise across all aspects of the ethanol supply, production, and distribution chain – from agribusiness, to plant operations and management, to commodity markets and risk management, to ethanol marketing and distribution. We believe the level of operational and financial expertise of our management team will prove critical in successfully executing our business strategies.

3

Our Business Strategies

We intend to continue our focus on strengthening and diversifying our vertically-integrated platform by implementing or continuing the following growth strategies:

Pursue Attractive Organic Growth Opportunities. We believe certain expansion projects could be implemented at our ethanol plants that have the potential to utilize the strategic location and capacity of these assets and cost effectively increase our annual production. We also intend to increase the grain storage capacity at our ethanol plants to take advantage of our existing infrastructure as well as strengthen relationships with local corn producers, allowing us to source corn more effectively and at a lower average cost. We intend to pursue opportunities to develop additional grain elevators at or near our ethanol plants. Since all of our plants are located within or near the corn belt where a number of competitors also have ethanol facilities, we believe that owning grain elevators provides us with a competitive advantage in the procurement of corn supplies.

Pursue Accretive Acquisitions and Consolidation Opportunities. We continue to focus on the potential acquisition of additional ethanol plants and grain elevators. In the past several years, we have been approached with opportunities to acquire ethanol plants. We believe those plants were available for a number of reasons including financial distress of a particular facility, a lack of operational expertise or a desire by existing owners to exit their original investment. We take a disciplined approach in evaluating new opportunities by considering whether the plants or grain elevators fit within our design, engineering, financial and geographic criteria. We believe that our integrated platform, plant operations experience and disciplined risk management approach give us the ability to generate favorable returns from chosen acquisitions.

Expand Marketing and Distribution Activities. We plan to continue expanding our downstream access to customers and seeking opportunities to arbitrage markets with minimal risk allocation. We currently participate in ethanol logistic, transload services and continually seek opportunities to expand the capacity of these facilities through organic growth. We intend to seek acquisition of fuel terminal facilities that involve conventional, as well as renewable, fuels. We believe the expansion of our capacity will encourage the distribution of blended fuel and enable us to continue to capitalize on our vertically-integrated platform.

Conduct Safe, Reliable, Efficient Operations and Improve Operational Efficiency. We are committed to maintaining the safety, reliability, environmental compliance and efficiency of our operations. All of our assets are staffed by experienced industry personnel. We will also continue to focus on incremental operational improvements to enhance overall production results. We continually research operational processes that may increase our efficiency by increasing yields, lowering processing cost per gallon and increasing production volumes. Additionally, we employ an extensive production control system at each plant to continuously monitor its performance. We are able to use the plants’ performance data to develop strategies for cost reduction and efficiency that can be applied across our platform.

Invest in Adjacent Businesses to Take Advantage of Our Competencies. In June 2014, we acquired the assets of a cattle-feeding business near Kismet, Kansas. We plan to continue to seek acquisitions of adjacent businesses, including additional feedlots, that will allow us to apply our commodity processing and trading expertise as a competitive advantage in selected agricultural and energy markets. We believe we have specialized knowledge, existing processes and an expandable infrastructure that can be successfully applied to other business operations that involve commodity processing. In addition, we are continuing our investment in the BioProcess Algae joint venture, which is focused on the commercialization of advanced photo-bioreactor technologies for the growing and harvesting of algal biomass, which can be used as high-quality feedstocks with a number of high-value applications in human nutrition, pharmaceutical applications, animal feed, chemicals and biofuels. We believe this technology has specific applications for facilities that emit carbon dioxide, including ethanol plants.

Ethanol Industry Overview

Ethanol (also known as ethyl alcohol or grain alcohol) is a clear, colorless liquid made by fermenting and distilling material, usually from plants. The ethanol we produce is fuel grade, principally from the starch extracted from corn, and is primarily used in the blending of gasoline. In the United States, corn is the most common product used to produce ethanol. One bushel of corn produces about 2.8 gallons of ethanol and 17 pounds of distillers’ grains, a high-protein livestock feed for our food supply. To reduce corn transportation costs, most ethanol plants are located near areas where corn is grown; therefore the majority of U.S. ethanol plants are located in the midwestern region, commonly referred to as the corn belt. Outside the Unites States, including Brazil, sugarcane is the primary feedstock used in ethanol production.

4

The fuel ethanol industry is a key component of the biofuels industry. Biofuels are transportation fuels that are derived from renewable biological materials and are typically blended with gasoline, diesel fuel and other petroleum-based transportation fuels as they are a good source for oxygenates and octanes. When added to petroleum-based transportation fuels, oxygenates enable a cleaner-burning fuel, thereby reducing tailpipe pollution and carbon monoxide emissions. Oxygenates are not only utilized for their vehicle emission benefits, but also for their blending properties in motor gasoline as a fuel extender and a fuel enhancer as an octane booster. Globally, including within in the United States, ethanol is an economical source of both oxygenate and octane for blending into the fuel supply.

The ethanol industry is growing worldwide as ethanol production is cost competitive with gasoline. Additionally, due to its environmental and economic benefits, approximately 30 countries either mandate or incentivize ethanol and bio-diesel blending for motor fuels. These policies are often motivated partly by the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or air pollution and partly by the desire to be less dependent on oil imports. The worldwide fuel ethanol industry has grown significantly over the past decade, with annual reported production increasing from approximately 5.0 billion gallons in 2001 to approximately 23.4 billion gallons in 2013, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, or EIA. Furthermore, the United States and Brazil are the two largest producers and exporters of ethanol in the world. Over the same time frame, the U.S. ethanol industry grew from 1.8 billion gallons to 13.3 billion gallons. Today, ethanol comprises approximately 10% of the U.S. gasoline market.

In the United States, ethanol is mandated by the federal government. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, uses renewable identification numbers, or RINs, to track renewable transportation fuels and to monitor compliance with the Renewable Fuel Standard, or RFS, a federal program that requires transportation fuels sold in the United States to contain minimum volumes of renewable fuels. The RFS program assigns obligated parties (fuel refiners, blenders and importers) a renewable volume obligation. The renewable volume obligation for each party is the volume of renewable fuels it is obligated to sell, based on a percentage of the company's total fuel sales, and is met by blending a certain quota of renewable fuel, such as ethanol, into gasoline. Obligated parties utilize RINs to track and show proof of compliance that they have met their RFS-mandated volumes. RINs are bought and sold among obligated parties and producers to fulfill quotas of renewable fuels during the blending process. Parties that produce or own RINs must register with the EPA and comply with RINs record and reporting guidelines on a quarterly basis.

We believe ethanol, as a proportion of global transportation fuels, will continue to remain consistent, or potentially increase, due to a continuing focus on reducing reliance on petroleum-based transportation fuels. Contributing factors include volatile oil prices, heightened environmental concerns, energy independence and national security concerns. We believe ethanol’s high octane value, environmental benefits, ability to improve gasoline performance, fuel supply extender capabilities, attractive production economics and favorable government policies could enable ethanol to comprise an increasingly larger portion of the global fuel supply, as described more fully below:

|

· |

Emissions Reduction. Ethanol demand increased substantially in the 1990’s, when federal law began requiring the use of oxygenates in reformulated gasoline in cities with unhealthy levels of air pollution on a seasonal or year-round basis. These oxygenates included ethanol and methyl tertiary-butyl ether, or MTBE, which reduce vehicle emissions when blended with gasoline. Oxygenated gasoline is used in order to help meet separate federal and state air emission standards. In the United States, the refining industry has all but abandoned the use of MTBE, making ethanol the primary clean air oxygenate currently used. |

|

· |

Octane Enhancer. Ethanol, with an octane rating of 113, is used to increase the octane value of gasoline with which it is blended, thereby improving engine performance. It is used as an octane enhancer both for producing regular grade gasoline from lower octane blending stocks and for upgrading regular gasoline to premium grades. The domestic gasoline market continues to evolve as refiners are producing more conventional blendstocks for oxygenate blending, or CBOB. According to data gathered by the EIA, CBOB represents approximately 80% of total conventional gasoline sold in 2014. CBOB is an 84 octane sub-grade gasoline, which requires ethanol or other octane sources to meet the minimum octane rating requirements for the U.S. gasoline market. Ethanol has become the primary additive used by refiners to increase octane levels. |

|

· |

Fuel Stock Extender. Ethanol is a valuable blend component that is used by refiners in the United States to extend fuel supplies. According to the EIA, from 2001 to 2014, ethanol as a component of the United States gasoline supply has grown from 1.4% to 9.9%. In 2014 alone, ethanol replaced the need for approximately 712 million barrels of oil in the United States. |

5

|

· |

E15 Blending Waiver. Through a series of decisions beginning in October 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, has granted a waiver for the use of up to 15% ethanol blended with gasoline, or E15, in model year 2001 and newer passenger vehicles, including cars, sport utility vehicles, or SUVs, and light pickup trucks. In June 2012, the EPA gave final approval for the sale and use of E15 ethanol blends. The nation’s first retail E15 ethanol blends were sold in July 2012. As of January 20, 2015, there were 110 retail fuel stations in 16 states offering E15 to consumers. |

|

· |

Mandated Use of Renewable Fuels. The growth in ethanol usage in the United States has also been supported by legislative requirements dictating the use of renewable fuels, including ethanol. The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, or EISA, established the Renewable Fuel Standard II, or RFS II, which modified a renewable fuel standard established in previous legislation. RFS II mandated a minimum usage of corn-derived renewable fuels of 12.0 billion gallons in 2010, increasing annually by 600 million gallons to 15.0 billion gallons in 2015. Under the provisions of EISA, authority has been delegated to the EPA to assign mandated volumes of renewable fuels to be blended into transportation fuel to individual fuel blenders. The EPA has not set mandated volumes for 2014 or 2015. RFS II, has been, and we expect will continue to be, a driving factor in the growth of ethanol usage. |

|

· |

Net Ethanol Exports. Prior to 2010, the United States had a long history as a net importer of ethanol. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or USDA, in 2010, the United States became the global low-cost ethanol producer, surpassing Brazil as the largest exporter of ethanol to world markets. According to the EIA, U.S. ethanol exports, net of imports, in 2014 were approximately 750 million gallons and in 2013 were approximately 200 million gallons. |

Our Operating Segments

Ethanol Production Segment

We have the capacity to produce over one billion gallons of ethanol per year within our ethanol production segment. Our plants use a dry mill process to produce ethanol and co-products such as wet, modified wet or dried distillers grains. Processing at full capacity, our plants consume approximately 360 million bushels of corn and produce approximately 2.9 million tons of distillers grains annually. Each of our plants is located adjacent to and has access to major rail lines. We operate all of our ethanol plants through wholly-owned operating subsidiaries. A summary of these plants is outlined below:

|

Plant |

Plant Production Capacity (mmgy) |

Initial Operation or Acquisition Date |

Technology |

Land Owned (acres) |

On-Site Ethanol Storage Capacity (gallons) |

|

Atkinson, Nebraska |

50 |

June 2013 |

Delta-T |

80 |

2,074,000 |

|

Bluffton, Indiana (1) |

120 |

Sept. 2008 |

ICM |

419 |

3,000,000 |

|

Central City, Nebraska |

100 |

July 2009 |

ICM |

40 |

2,250,000 |

|

Fairmont, Minnesota |

115 |

Nov. 2013 |

Delta-T |

209 |

3,124,000 |

|

Lakota, Iowa |

100 |

Oct. 2010 |

ICM/Lurgi |

91 |

2,500,000 |

|

Obion, Tennessee (1) |

120 |

Nov. 2008 |

ICM |

230 |

3,000,000 |

|

Ord, Nebraska |

55 |

July 2009 |

ICM |

171 |

1,550,000 |

|

Otter Tail, Minnesota |

60 |

Mar. 2011 |

Delta-T |

117 |

2,000,000 |

|

Riga, Michigan |

60 |

Oct. 2010 |

Delta-T |

137 |

1,239,000 |

|

Shenandoah, Iowa (1) |

65 |

Aug. 2007 |

ICM |

110 |

1,524,000 |

|

Superior, Iowa (1) |

60 |

July 2008 |

Delta-T |

263 |

1,238,000 |

|

Wood River, Nebraska |

115 |

Nov. 2013 |

Delta-T |

126 |

3,124,000 |

|

(1) |

We constructed these four plants; all other ethanol plants were acquired. |

Six of the twelve plants we own are what we believe to be industry-leading ethanol processing technology developed by ICM, Inc. The remaining six plants are Delta-T technology, which is also a quality processing technology in the ethanol industry. Our years of combined experience with building, acquiring and operating these technologies provides us with a deep understanding of how to effectively and efficiently manage both systems for maximum performance.

6

Corn Feedstock and Ethanol Production

Ethanol is a chemical produced by the fermentation of carbohydrates found in grains and other biomass. Ethanol can be produced from a number of different types of grains, such as corn, wheat and sorghum, as well as from agricultural waste products such as rice hulls, cheese whey, potato waste, brewery and beverage wastes and forestry and paper wastes. At present, the majority of ethanol in the United States is produced from corn because corn contains large quantities of carbohydrates, can be handled efficiently and is in greater supply than other grains. Such carbohydrates convert into glucose more easily than most other kinds of biomass. Outside the United States, sugarcane is the primary feedstock used in ethanol production.

Our plants use corn as feedstock in the dry mill ethanol production process. Each of our plants requires, depending on their production capacity, approximately 20 million to 40 million bushels of corn annually. The price and availability of corn are subject to significant fluctuations depending upon a number of factors that affect commodity prices in general, including crop conditions, weather, governmental programs and foreign purchases. Because the market price of ethanol is not directly related to corn prices, ethanol producers are generally not able to compensate for increases in the cost of corn feedstock through adjustments to prices charged for their ethanol.

Our corn supply is obtained primarily from local markets. To utilize synergies between our agribusiness and ethanol production segments, corn is procured by our agribusiness segment and subsequently provided to our ethanol production segment. We utilize cash and forward purchase contracts with grain producers and elevators for the physical delivery of corn to our plants. At seven of our ethanol plants, we maintain direct relationships with local farmers, grain elevators and cooperatives, which serve as our primary sources of grain feedstock. Most farmers in the areas where these plants are located store their corn in their own storage facilities, which allows us to purchase much of the corn needed to supply our plants directly from farmers throughout the year. At five of our ethanol plants, we have contracted with third-party grain originators to supply all corn required for ethanol production. These contracts terminate between September 2015 and November 2023. Each of our plants is also situated on rail lines or has other logistical solutions to access corn supplies from other regions of the country if local corn supplies are insufficient.

Corn is received at the plant by truck or rail, is then weighed and unloaded in a receiving building. Storage bins are utilized to inventory grain, which is passed through a scalper to remove rocks and debris prior to processing. Thereafter, the corn is transported to a hammer mill where it is ground into coarse flour and conveyed into a slurry tank for enzymatic processing. Water, heat and enzymes are added to convert the complex starch molecules into simpler carbohydrates. The slurry is heated to reduce the potential of microbial contamination and pumped to a liquefaction tank where additional enzymes are added. Next, the grain slurry is pumped into fermenters, where yeast, enzymes, and nutrients are added, to begin a batch fermentation process. A beer column, within the distillation system, separates the alcohol from the spent grain mash. Alcohol is then transported through a rectifier column, a side stripper and a molecular sieve system where it is dehydrated to 200-proof alcohol. The 200-proof alcohol is either pumped to a holding tank and blended with approximately two percent denaturant (usually natural gasoline) as it is pumped into finished product storage tanks or is marketed as undenatured ethanol.

Distillers Grains

The spent grain mash from the beer column is pumped into one of several decanter type centrifuges for dewatering. The water, or thin stillage, is pumped from the centrifuges and then to an evaporator where it is dried into a thick syrup. The solids, or wet cake, that exit the centrifuge are conveyed to the dryer system. The wet cake is dried at varying temperatures, resulting in the production of distillers grains. Syrup might be reapplied to the wet cake prior to drying, providing additional nutrients to the distillers grains. Distillers grains, the principal co-product of the ethanol production process, are principally used as high-protein, high-energy animal fodder and feed supplements marketed to the dairy, beef, swine and poultry industries.

Dry mill ethanol processing potentially creates three forms of distillers grains, depending on the number of times the solids are passed through the dryer system: wet, modified wet and dried distillers grains. Wet distillers grains are processed wet cake that contains approximately 65% to 70% moisture. Wet distillers grains have a shelf life of approximately three days and can be sold only to dairies or feedlots within the immediate vicinity of an ethanol plant. Modified wet distillers grains, which have been dried further to approximately 50% to 55% moisture, have a slightly longer shelf life of approximately three weeks and are marketed to regional dairies and feedlots. Dried distillers grains, which have been dried more extensively to approximately 10% to 12% moisture, have an almost indefinite shelf life and may be stored, sold and shipped to any market regardless of its proximity to an ethanol plant.

7

The production of ethanol requires significant amounts of natural gas, electricity and water.

Natural Gas. Ethanol plants produce process steam from their own boiler systems and dry the distillers grains co-product via direct gas-fired dryers. Depending on certain production parameters, our ethanol plants are expected to use approximately 22,000 to 32,000 British Thermal Units of natural gas per gallon of production. We have entered into certain service agreements for the natural gas required by our ethanol plants and pay tariff fees to these providers for transporting the gas through their pipelines to our plants.

Electricity. Our plants require between 0.5 and 1.0 kilowatt hours of electricity per gallon of production. Local utilities supply necessary electricity to all of our ethanol plants.

Water. Although some of our plants satisfy the majority of their water requirements from wells located on their respective properties, each plant also obtains potable water from local municipal water sources. Each facility operates a filtration system to purify the well water that is utilized for its operations. Local municipalities supply all of the necessary water for our plants that do not have onsite wells. Much of the water used in an ethanol plant is recycled back into the production process.

Corn Oil Production Segment

We operate corn oil extraction systems at our ethanol plants. The corn oil systems are designed to extract non-edible corn oil from the thin stillage evaporation process immediately prior to production of distillers grains. Corn oil is produced by processing syrup and evaporated thin stillage through a decanter style centrifuge or a disk stack style centrifuge. Corn oil has a lower density than water or solids which make up the syrup. The centrifuges separate the relatively light oil from the heavier components of the syrup, eliminating the need for significant retention time. We extract approximately 0.7 pounds of corn oil per bushel of corn used to produce ethanol. De-oiled syrup is returned to the process for blending into wet, modified, or dry distillers grains. Industrial uses for corn oil include feedstock for biodiesel, livestock feed additives, rubber substitutes, rust preventatives, inks, textiles, soaps and insecticides.

8

Agribusiness Segment

We own and operate four grain elevators in three states with combined grain storage capacity of approximately 9.0 million bushels. Our cattle-feeding operation has approximately 2,600 acres of land, with 3.8 million bushels of grain storage capacity and the ability to support 70,000 head of cattle. Our ethanol plants have approximately 29.4 million bushels of total grain storage capacity. A summary of our agribusiness segment facilities is outlined below:

|

Facility Location |

Land Owned (acres) |

On-Site Grain Storage Capacity (bushels) |

|

Grain Elevators |

||

|

Archer, Nebraska |

12 |

1,200,000 |

|

Essex, Iowa |

17 |

3,700,000 |

|

Hopkins, Missouri |

10 |

2,000,000 |

|

St. Edward, Nebraska |

9 |

2,100,000 |

|

Feedlot Operation |

||

|

Kismet, Kansas |

2,600 |

3,800,000 |

|

Ethanol Plants |

||

|

Atkinson, Nebraska |

* |

2,280,000 |

|

Bluffton, Indiana |

* |

4,789,000 |

|

Central City, Nebraska |

* |

1,400,000 |

|

Fairmont, Minnesota |

* |

1,611,000 |

|

Lakota, Iowa |

* |

3,532,000 |

|

Obion, Tennessee |

* |

2,422,000 |

|

Ord, Nebraska |

* |

2,266,000 |

|

Otter Tail, Minnesota |

* |

2,504,000 |

|

Riga, Michigan |

* |

2,321,000 |

|

Shenandoah, Iowa |

* |

636,000 |

|

Superior, Iowa |

* |

2,477,000 |

|

Wood River, Nebraska |

* |

3,199,000 |

* Land owned at the ethanol plant locations is disclosed in the ethanol segment discussion above.

We buy bulk grain, primarily corn and soybeans, and cattle from area producers and provide grain drying and storage services to those producers. Our bulk grain business supplies a portion of the feedstock for our ethanol plants. The grain is also sold to grain processing companies and area livestock producers while cattle are sold to meat processors. Bulk grain and cattle commodities are readily traded on commodity exchanges and inventory values are affected by market changes and spreads. In an attempt to reduce risks due to market fluctuations from purchase and sale commitments for grain and cattle, as well as grain and cattle held in inventory, we enter into exchange-traded futures and options contracts that function as economic hedges. We believe our agribusiness operations increase our operational efficiency, reduce commodity price and supply risks, and diversify our revenue streams.

Seasonality is present within our agribusiness operations. The fall harvest period generally results in higher handling margins and stronger financial results for this segment during the fourth quarter.

Marketing and Distribution Segment

We have an in-house marketing business responsible for the sale, marketing and distribution of all ethanol, distillers grains and corn oil produced at our ethanol plants. We also market and provide logistical services for ethanol and other commodities for a third-party ethanol producer. We purchase and sell ethanol, distillers grains, corn oil, grain, natural gas and other commodities in various markets. Additionally, we operate eight fuel terminals, with approximately 822 mmgy of total throughput capacity, allowing us to source, store and distribute biodiesel and ethanol, including our production and that of other producers, across multiple states.

9

Marketing

We market our ethanol and that of a third-party producer to many different customers on a local, regional, national and international basis. In addition, we purchase ethanol from other independent producers to realize price arbitrages that may exist. To achieve the best prices for the ethanol that we market, we sell into various markets under sales agreements with integrated energy companies, jobbers, retailers, traders and resellers. Under these agreements, ethanol is priced under fixed and indexed pricing arrangements. We produce ethanol that conforms to domestic and certain international specifications; accordingly, our ethanol is also sold to buyers for export to Brazil, Canada, Europe and other international markets.

The market for distillers grains generally consists of local markets for wet, modified wet and dried distillers grains, and national and international markets for dried distillers grains. In addition, the market can be segmented by geographic region and livestock industry. The bulk of the current demand is for deliveries to geographic regions without significant local corn or distillers grains production. Our market strategy includes shipping a substantial amount of distillers grains as dried distillers grains to regional and national markets by barge and rail.

Most of our modified wet distillers grains are sold to midwestern feedlot markets. Our dried distillers grains are generally shipped to feedlot and poultry markets, as well as to Texas and west coast rail markets. Some of our distillers grains are shipped by truck to dairy, beef, and poultry operations in the eastern United States. Also, at certain times of the year, we transport product to the Mississippi River to be loaded on barges. We also ship by railcars into Eastern and Southeastern feed mill, poultry and dairy operations, as well as to domestic trade companies. We also sell dried distillers grains to exporters for shipment to international markets. The largest distillers grains export markets in 2014 included China, Mexico, Vietnam, and South Korea. Access to diversified markets allows us to sell product to customers that are offering the highest net price.

Our corn oil is primarily sold to biodiesel manufactures and, to a lesser extent, feed lot and poultry markets. We generally transport our corn oil by truck to locations in a close proximity to our ethanol plants, primarily in the southeastern and midwestern regions of the United States.

Transportation and Delivery

Most ethanol plants are situated near major highways or rail lines to ensure efficient movement. The distribution of ethanol primarily consists of movements from ethanol plants to bulk terminals via railcar, transport truck or barge. It is difficult to transport ethanol in pipelines because it is water-soluble and, as a result, will mix readily with any water present in a pipeline. We manage the logistics and transportation requirements of our customers to improve efficiencies of our fleet and reduce operating costs.

To meet the challenge of marketing ethanol and distillers grains to diverse market segments, our plants generally have access to rail lines, with several having extensive rail siding capable of handling more than 150 railcars on-site. At certain of our locations, we have large loop tracks which enable loading of unit trains of both ethanol and dried distillers grains, as well as spurs connecting the site’s rail loop to the railroad mainline or spurs that allow movement and storage of railcars on-site. These rail lines allow us to sell our products to various regional and national markets. The rail providers for our ethanol plants can switch cars to most of the other major railroads, allowing the plants to ship ethanol and distillers grains throughout the United States. Our railcar fleet is comprised of approximately 2,200 leased tank cars for the transportation of ethanol and approximately 900 leased hopper cars for the transportation of distillers grains. The lease contract initial terms are for periods up to ten years. Deliveries to the majority of the local markets, within 150 miles of the plants, are generally transported by truck, and deliveries to more distant markets are shipped by rail using major U.S. rail carriers. We seek to optimize the utilization of our rail assets, including potential use for transportation of products other than ethanol and distillers grains, depending on market opportunities. To optimize the value of our assets, we have utilized a portion of our railcar fleet to transport crude oil for third parties and to lease railcars to other users.

Terminal and Distribution Services

Once stored in our terminal facilities near our plants, ethanol is transported to third-party blending terminals where it is then blended with gasoline to the appropriate level. Ethanol blending typically occurs at the rack level where the two products are combined in the proper proportion and transferred on to the loading rack for delivery into the transport truck, which then transports the blended gasoline to retail gas stations.

10

We own and operate fuel holding tanks and terminals, and provide terminal services and logistics solutions to markets that currently do not have efficient access to renewable fuels. We operate fuel terminals at one owned and seven leased locations on approximately 28 acres in seven states with a combined total storage capacity of approximately 7.4 million gallons and throughput capacity of approximately 822 mmgy. The fuel terminal facilities are summarized below:

|

Facility Location |

Storage Capacity (gallons) |

Throughput Capacity (mmgy) |

|

Birmingham, Alabama - Unit Train Terminal |

6,542,000 |

300 |

|

Birmingham, Alabama - Other |

120,000 |

72 |

|

Bossier City, Louisiana |

180,000 |

60 |

|

Collins, Mississippi |

180,000 |

180 |

|

Little Rock, Arkansas |

30,000 |

36 |

|

Louisville, Kentucky |

60,000 |

30 |

|

Nashville, Tennessee |

160,000 |

60 |

|

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

150,000 |

84 |

Risk Management and Hedging Activities

The profitability of our operations and our industry are highly dependent on commodity prices, especially prices for ethanol, distillers grains, corn oil, corn and natural gas. Because market price fluctuations among these commodities are not always correlated, at times ethanol production may be unprofitable.

We enter into forward contracts to sell a portion of our respective ethanol and distillers grains production or to purchase a portion of our respective corn or natural gas requirements in an attempt to partially offset the effects of volatility of ethanol, distillers grains, corn and natural gas prices. We also engage in other hedging transactions involving exchange-traded futures contracts for corn, natural gas and ethanol from time to time. The financial statement impact of these activities is dependent upon, among other things, the prices involved and our ability to physically receive or deliver the commodities involved. Hedging arrangements also expose us to the risk of financial loss in situations where the counterparty to the hedging contract defaults on its contract or, in the case of exchange-traded contracts, where there is a change in the expected differential between the price of the commodity underlying the hedging agreement and the actual prices paid or received by us for the physical commodity bought or sold. Hedging activities can themselves result in losses when a position is purchased in a declining market or a position is sold in a rising market. A hedge position is often settled in the same time frame as the physical commodity is either purchased (corn and natural gas) or sold (ethanol, distillers grains and corn oil). Hedging losses may be offset by a decreased cash price for corn and natural gas and an increased cash price for ethanol, distillers grains and corn oil. We also vary the amount of hedging or other risk mitigation strategies we undertake, and we may choose not to engage in hedging transactions at all. By using a variety of risk management tools and hedging strategies, including our internally-developed real-time operating margin management system, we believe our approach to risk management allows us to monitor real-time operating price risk exposure at each of our plants and to respond quickly to lock in acceptable margins when they are available or temporarily reduce production levels at our ethanol plants during periods in which we have identified compressed margins. In addition, our multiple business lines and revenue streams help diversify our operations and profitability.

Recent Acquisition and Disposition Activity

In January 2012, we acquired a grain elevator located in St. Edward, Nebraska. The grain elevator is located approximately 40 miles from our Central City, Nebraska ethanol plant and is included in our agribusiness segment.

In December 2012, we sold 12 grain elevators located in northwestern Iowa and western Tennessee. The sale of assets, previously included in our agribusiness segment, consisted of approximately 32.6 million bushels of grain storage capacity and all of our agronomy and retail petroleum operations.

In June 2013, we acquired an ethanol plant located in Atkinson, Nebraska. The plant, which is part of our ethanol production segment, has production capacity of approximately 50 mmgy, adding to our ethanol and distillers grains production. Corn oil extraction technology was installed at the plant late in the fourth quarter of 2013. Also, in June 2013, we acquired a grain elevator in Archer, Nebraska, which is included in our agribusiness segment.

11

In November 2013, we acquired two ethanol plants, located in Wood River, Nebraska and Fairmont, Minnesota. The plants, which are part of our ethanol production segment, have combined production capacity of 230 mmgy, adding to our ethanol, distillers grains and corn oil production. The Fairmont, Minnesota plant, which was not operational at the time of its acquisition, began operations in January 2014 upon completion of certain maintenance and enhancement projects.

In June 2014, we acquired the assets of a cattle-feeding business near Kismet, Kansas, which includes a feedlot and grain storage facility. The operation, which is part of our agribusiness segment, consists of approximately 2,600 acres of land, which has the capacity to support 70,000 head of cattle, and corn storage capacity of approximately 3.8 million bushels.

BioProcess Algae Joint Venture

Our BioProcess Algae joint venture is focused on developing technology to grow and harvest algae, which consume carbon dioxide, in commercially viable quantities. Through multiple stages of expansion, BioProcess Algae has constructed a five-acre algae farm next to our Shenandoah, Iowa ethanol plant and has been operating its Grower Harvesters™ bioreactors since January 2011. The joint venture is currently focused on verification of growth rates, energy balances, capital requirements and operating expenses of the technology, which are considered to be some of the key steps to commercialization.

BioProcess Algae announced on April 22, 2013, that it had been selected to receive a grant of up to $6.4 million from the U.S. Department of Energy, or DOE, as part of a pilot-scale biorefinery project related to production of hydrocarbon fuels meeting military specification. The project uses renewable carbon dioxide, lignocellulosic sugars and waste heat through BioProcess Algae’s Grower Harvester™ technology platform. The objective of the project is to demonstrate technologies to cost-effectively convert biomass into advanced drop-in biofuels. BioProcess Algae is required to contribute a minimum of 50% matching funds for the project. The project with the DOE has been divided into three phases, with the first phase successfully completed in August 2014. We have agreed with the DOE to move into the second phase in which the detailed design, engineering, scheduling and budgeting for construction of a pilot-scale integrated biorefinery will be developed. The third phase would involve construction of the biorefinery.

If we and the other BioProcess Algae members determine that the joint venture can achieve the desired economic performance, a larger build-out will be considered, possibly as large as 200 to 400 acres of Grower Harvester™ reactors. Such a build-out may be completed in stages and could take up to two years to complete. Funding for such a project would come from a variety of sources, including current partners, new equity investors, debt financing or a combination thereof. We increased our ownership of BioProcess Algae to approximately 63% during the second quarter of 2014. However, we still do not possess the requisite control of this investment to consolidate it.

Our Competition

Domestic Ethanol Competitors

We compete with numerous other ethanol producers located throughout the United States. In 2014, the three largest ethanol producers in North America were Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, POET, LLC and Valero Energy Corporation. We believe that our principal competitors’ expected managed annual production capacity and ethanol marketed ranges between approximately 300 mmgy and approximately 1,800 mmgy. Based on production capacity as reported by Ethanol Producer Magazine, we believe we are the fourth largest ethanol producer in North America. According to Ethanol Producer Magazine, as of December 31, 2014, there were 213 ethanol-producing plants within the United States, capable of producing 15.9 billion gallons of ethanol annually. The industry typically does not operate at 100% of capacity with historical rates of annual production to available plant capacity averaging in the high 80 percent to the low 90 percent range.

Our competitors also include plants owned by farmers who earn their primary livelihood through the production and sale of grain and competitors whose primary business is oil refining and retail fuel sales. These competitors may continue to operate their plants when market conditions are uneconomic due to benefits realized in other operations.

Competition for corn supply from other ethanol plants and other corn consumers exists in all areas and regions in which our plants operate. According to Ethanol Producer Magazine, as of December 31, 2014, the states of Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska and Tennessee had a total of 113 operational ethanol plants, with Iowa and Nebraska having the majority of the plants. The state of Iowa had 44 operational ethanol plants concentrated, for the most part, in the northern and central regions of the state where a majority of the corn is produced. The state of Nebraska had 26 operational ethanol plants.

12

Foreign Ethanol Competitors

We also face foreign competition in the production of ethanol. Brazil is currently the second largest ethanol producer in the world. Brazil’s ethanol production is sugarcane based, as opposed to corn based, and, depending on feedstock prices, may be less expensive to produce. Under RFS II, certain parties were obligated to meet an advanced biofuel standard calling for 3.75 billion gallons of biofuels in 2014. In recent years, sugarcane ethanol imported from Brazil has been one of the most economical means for obligated parties to meet this standard. Other foreign producers may be able to produce ethanol at lower input costs, including costs of feedstock, facilities and personnel, than we can. If significant additional foreign ethanol production capacity is created, such facilities could create excess supplies of ethanol on world markets, which may result in lower prices of ethanol throughout the world, including the United States.

Other Competition

Alternative fuels, gasoline oxygenates and ethanol production methods are continually under development by ethanol and oil companies. Ethanol production technologies continue to evolve, and changes are expected to occur primarily in the area of ethanol made from cellulose obtained from other sources of biomass such as switchgrass or fast-growing poplar trees. Because our plants are designed as single-feedstock facilities, we have limited ability to adapt the plants to a different feedstock or process system without additional capital investment and retooling.

Regulatory Matters

Government Ethanol Programs and Policies

Demand for cleaner, more sustainable transportation fuels is growing around the world. Growth of ethanol demand is being driven by progressive policies adopted by more than 30 foreign countries, calling for increasing amounts of ethanol in those countries’ motor fuel supplies. Ethanol has become crucial to the global fuel mix, providing an economical source of oxygenate and octane for global fuel supplies.

In an effort to reduce this country’s dependence on foreign oil, federal and state governments have enacted numerous policies, incentives and subsidies to encourage the usage of domestically-produced alternative fuels. The U.S. ethanol industry has benefited significantly as a direct result of these policies. While historically the ethanol industry has been dependent on economic incentives, the need for such incentives has and may continue to diminish as the acceptance of ethanol as a primary fuel and as a fuel extender continues to increase.

Pursuant to the provisions of EISA, RFS II was established, which modified a renewable fuel standard established in previous legislation. RFS II increased the volume of renewable fuel required to be blended into transportation fuel and mandated a minimum usage of corn-derived renewable fuels of 12.0 billion gallons in 2010, increasing annually by 600 million gallons to 15.0 billion gallons in 2015. Under the provisions of EISA, authority has been delegated to the EPA to assign mandated volumes of renewable fuels to be blended into transportation fuel to individual fuel blenders. RFS II, has been, and we expect will continue to be, a driving factor in the growth of ethanol usage in the United States. On April 10, 2013 the Renewable Fuel Standard Elimination Act was introduced as H.R. 1461 to target the repeal of RFS II. Also introduced on April 10, 2013 was the RFS Reform Bill, H.R. 1462, which would prohibit more than ten percent ethanol in gasoline and reduce the RFS II mandated volume of renewable fuel. On May 14, 2013, the Domestic Alternatives Fuels Act of 2013 was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives as H.R. 1959 to allow ethanol produced from natural gas to be used to meet the RFS II mandate. These bills failed to make it out of congressional committee and were not enacted into law. H.R. 21 was introduced on January 6, 2015 to provide for a comprehensive assessment of the scientific and technical research on the implications of the use of mid-level ethanol blends, and for other purposes. This bill would seek to eliminate the waiver granted by the EPA to allow E15 in 2001 and newer model cars and light trucks. H.R. 434 was introduced on January 21, 2015 which seeks to modify the Clean Air Act by limiting or removing the authority of the EPA to grant waivers for higher blends of ethanol in the U.S. gasoline supply. The bill also seeks to repeal existing waivers already granted by the EPA concerning E15. H.R.704, introduced February 4, 2015, is similar to H.R. 21 as it proposes limiting ethanol blends higher than 10% in the U.S. fuel supply and seeks to repeal the renewable fuel standard.

Under the provisions of EISA, the EPA has the authority to waive the mandated RFS II requirements in whole or in part. To grant the waiver, the EPA administrator must determine, in consultation with the Secretaries of Agriculture and Energy, that one of two conditions has been met: (1) there is inadequate domestic renewable fuel supply or (2) implementation of the requirement would severely harm the economy or environment of a state, region or the United States. In the third quarter of

13

2012, several waiver requests were filed with the EPA based on drought conditions, which were subsequently denied.

The RFS II mandate increased to 14.4 billion gallons of corn-derived renewable fuel for 2014, 600 million gallons over the mandated volume in 2013, and increases to 15.0 billion gallons for 2015. On November 15, 2013, the EPA released its Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for the 2014 Renewable Fuel Standard. The proposal discusses a variety of approaches for setting the 2014 standards, and includes a number of production and consumption ranges for key categories of biofuel covered by RFS II. The proposal seeks comment on a range of total renewable fuel volumes for 2014 and proposes a level within that range of 15.2 billion gallons, including approximately 13.0 billion gallons of corn-derived renewable fuel. The proposal addresses two constraints of RFS II: (1) limitations in the volume of ethanol that can be consumed in gasoline given practical constraints on the supply of higher ethanol blends to the vehicles that can use them and (2) limitations in the ability of the industry to produce sufficient volumes of qualifying renewable fuel. On November 21, 2014, the EPA announced that it rescinded its proposal from 2013 and will not be finalizing 2014 applicable percentage standards under the RFS program before the end of 2014. In light of this delay in issuing the 2014 RFS standards, the compliance demonstration deadline for the 2013 RFS standards will take place in 2015. The EPA will be making modifications to ensure that RINs generated in 2012 are valid for demonstrating compliance with the 2013 applicable standards.

To measure compliance with RFS II, RINs are generated and are attached to renewable fuels, such as the ethanol we produce, and detached when the renewable fuel is blended into the transportation fuel supply. Detached RINs may be retired by obligated parties to demonstrate compliance with RFS II or may be separately traded in the market. The market price of detached RINs may affect the price of ethanol in certain U.S. markets as obligated parties may factor these costs into their purchasing decisions. Moreover, at certain price levels for various types of RINs, it becomes more economical to import foreign sugar cane ethanol. If changes to RFS II result in significant changes in the price of various types of RINs, it could negatively affect the price of ethanol, and our operations could be adversely impacted.

To further drive growth in the increased adoption of ethanol, Growth Energy, an ethanol industry trade association, and a number of ethanol producers requested a waiver from the EPA to increase the amount of ethanol blended into gasoline from the current 10% level, or E10, to a 15% level, or E15. Through a series of decisions beginning in October 2010, the EPA granted a waiver for the use of E15 in model year 2001 and newer passenger vehicles, including cars, SUVs and light pickup trucks. In June 2012, the EPA gave final approval for the sale and use of E15 ethanol blends. The nation’s first retail E15 ethanol blends were sold in July 2012. As of January 20, 2015, there were 110 retail fuel stations in 16 states offering E15 to consumers.

The Clean Air Act requires use of oxygenated gasoline in areas where winter time carbon monoxide levels exceed federal air quality standards. Without oxygenated gasoline, carbon monoxide emissions from gasoline-fueled vehicles tend to increase in cold weather. Winter-oxygenated gasoline programs are implemented by the individual states.

Changes in corporate average fuel economy standards, or CAFE, have also benefited the ethanol industry by encouraging use of E85 fuel products. CAFE provides an effective 54% efficiency bonus to flexible-fuel vehicles running on E85. Today, E85 is available at 2,804 fuel stations concentrated in 10 U.S. states. The EIA estimates that there are 14.2 million flexible-fuel vehicles in the United States, representing 6.3% of cars and light trucks on the road. It also estimates that approximately 200 million gallons of E85 were sold in 2013. Auto manufacturers may find it attractive to build more flexible-fuel trucks and sport utility vehicles that are otherwise unlikely to meet CAFE standards.

The Master Limited Partnership Parity Act was introduced on April 24, 2013 in the U.S. House of Representatives as H.R. 1696 to extend the publicly traded partnership ownership structure to renewable energy projects, including ethanol production. The legislation would provide a more level financing system and tax burden for renewable energy and fossil energy projects. H.R. 1696 did not advance out of committee during the 113th Congress; currently, the co-sponsors have not re-introduced the bill.

In addition to these federal standards, many states have taken other steps to encourage ethanol consumption including tax credits, mandated blend rates and subsidies.

On July 21, 2010, President Obama signed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, or the Reform Act, which, among other things, aims to improve transparency and accountability in derivative markets. While the Reform Act increases the regulatory authority of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, or CFTC, regarding over-the-counter derivatives, there is uncertainty on several issues related to market clearing, definitions of market participants, reporting, and capital requirements. While some of the details have been addressed in CFTC regulations, others remain and at this time we do not anticipate any material impact to our risk management strategy.

14

The Domestic Alternative Fuels Act of 2012 was introduced on January 18, 2012 in the U.S. House of Representatives and was re-introduced on March 15, 2013 as H.R. 1214 to provide liability protection for claims based on the sale or use of certain fuels and fuel additives. Passage of this bill would provide liability protection to consumers in the event they unintentionally put any transportation fuel into their motor vehicle for which such fuel has not been approved. Some automobile manufacturers have publicly stated that the use of fuels not approved in their owners’ manuals, such as E15, is considered misfueling and any resulting damage would not be covered by their warranties. The American Fuel Protection Act of 2013, or H.R. 2267, was introduced on June 5, 2013 in the U.S. House of Representatives to make the United States exclusively liable for certain claims of liability for damages resulting from, or aggravated by, the inclusion of ethanol in transportation fuel. These bills failed to advance out of congressional committee and were not enacted into law.

Environmental and Other Regulation

Our ethanol production and agribusiness activities are subject to environmental and other regulations. We obtain environmental permits to construct and operate our ethanol plants.

Ethanol production involves the emission of various airborne pollutants, including particulate, carbon dioxide, oxides of nitrogen, hazardous air pollutants and volatile organic compounds. In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court classified carbon dioxide as an air pollutant under the Clean Air Act in a case seeking to require the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide in vehicle emissions. In February 2010, the EPA released its final regulations on the RFS II. We believe these final regulations grandfather our plants at their current authorized capacity, though expansion of our plants above these levels will need to meet a threshold of a 20% reduction in greenhouse gas, or GHG, emissions from a 2005 baseline measurement to produce ethanol eligible for the RFS II mandate. In order to expand capacity at our plants, we may be required to obtain additional permits, achieve EPA “efficient producer” status under the pathway petition program, install advanced technology, or reduce drying of certain amounts of distillers grains.

Separately, the California Air Resources Board, or CARB, has adopted a Low Carbon Fuel Standard, or LCFS, requiring a 10% reduction in average carbon intensity of gasoline and diesel transportation fuels from 2010 to 2020. After a series of rulings that temporarily prevented CARB from enforcing these regulations, the State of California Office of Administrative Law approved the LCFS on November 26, 2012, and revised LCFS regulations took effect in January 2013. An Indirect Land Use Change, or ILUC, component is included in this lifecycle GHG emissions calculation which may have an adverse impact on the market for corn-based ethanol in California.

The U.S. ethanol industry has long relied on railroads to deliver its product to market. We lease approximately 2,200 tank cars. These tank cars may need to be retrofitted or replaced if new regulations proposed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, or DOT, to address concerns related to safety are adopted, which could in turn cause a shortage of compliant tank cars. The proposed regulations call for a phase out within four years of the use of legacy DOT-111 tank cars for transporting highly-flammable liquids, including ethanol. According to the proposed rule, the DOT expects about 66,000 tank cars to be retrofitted and about 23,000 cars to be shifted to transporting other liquids. The Canadian government has also proposed that its nation’s rail shippers use sturdier tank cars for transportation of crude oil and ethanol. Adoption of the proposed regulations, which could result in upgrades or replacements of our tank cars, would likely have an adverse effect on our operations as lease costs for tank cars would likely increase. Additionally, existing tank cars could be out of service for a period of time while such upgrades are made, tightening supply in an industry that is highly dependent on such railcars to transport its product. The DOT recently announced that the comprehensive crude-by-rail safety rule will be submitted to the White House for final review with hopes that the rule will be finalized by May 2015.