Attached files

| file | filename |

|---|---|

| 10-K/A - LIGHTLAKE THERAPEUTICS INC. 10-K - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093.htm |

| EX-3.I - EXHIBIT 3(I) - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093ex3i.htm |

| EX-32 - EXHIBIT 32 - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093ex32.htm |

| EX-10.5 - EXHIBIT 10.5 - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093ex10_5.htm |

| EX-10.4 - EXHIBIT 10.4 - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093ex10_4.htm |

| EX-10.6 - EXHIBIT 10.6 - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093ex10_6.htm |

| EX-31.2 - EXHIBIT 31.2 - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093ex31_2.htm |

| EX-31.1 - EXHIBIT 31.1 - OPIANT PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. | a6213093ex31_1.htm |

Exhibit

10.7

| (19) | [EUROPEAN PATENT OFFICE LOGO] |

[BAR

CODE]

(11) EP

1 681 057 B1

|

(12) EUROPEAN PATENT

SPECIFICATION

|

(45)

Date of publication and mention

|

(51)

Int Cl.:

|

|

|

of

the grant of the patent:

|

A61K 31/485 (2006.01)

|

A61P 25/30 (2006.01)

|

|

13.08.2008

Bulletin 2008/33

|

A61P 3/04 (2006.01)

|

(21) Application

number: 06396001.7

(22) Date of

filing: 10.01.2006

|

(54)

Use of naloxone for

treating eating disorders

|

Verwendung

von Naloxon zur Behandlung von Essstörungen

Utilisation

de Naloxone pour traiter les troubles alimentaires

(84)

Designated Contracting States:

AT

BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE

SI SK TR

(30)

Priority: 10.01.2005 US

31534

(43) Date

of publication of application: 19.07.2006 Bulletin

2006/29

(73) Proprietor:

Sinclair, John D. 02550

Evitskog (FI)

(72)

Inventor: Sinclair, John D.

02550 Evitskog (FI)

(74) Representative:

Hovi, Simo Pekka Tapani et al

Seppo Laine Oy,

Itämerenkatu

3 B

00180

Helsinki (FI)

(56)

References cited:

EP-A-

0 790

058 US-B1-

6 569 449

· FICHTER

M M: "DIE MEDIKAMENTOESE BEHANDLUNG VON ANOREXIA UND BULIMIA

NERVOSAEINEUEBERSICHTMEDICATIONFOR ANOREXIAAND BULIMIANERVOSA:A REVIEW"

NERVENARZT, SPRINGER VERLAG, BERLIN, DE, vol.64, no.1, 1993, pages21-35,

XP008016116 ISSN: 0028-2804

· DREWNOWSKI

A ET AL: "Naloxone, an opiate blocker, reduces the consumption of sweet high-fat

foods in obese and lean female binge eaters" AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL

NUTRITION 1995 UNITED STATES, vol. 61, no. 6, 1995, pages 1206-1212, XP002376723

ISSN: 0002-9165

· "Drug

treatment for binge-eating disorders" JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN DIETETIC

ASSOCIATION 1995 UNITED STATES, vol. 95, no. 11, 1995, page 1329, XP002376724

ISSN: 0002-8223

Note:

Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the

European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to

the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the

Implementing Regulations. Notice of opposition shall not be deemed to have been

filed until the opposition fee has been paid. (Art. 99(1) European Patent

Convention).

2

EP

1 681 057 B1

Description

Background of the

Invention

Field of the

Invention

[0001] The present invention

relates to the treatment of eating disorders. In particular, the invention

relates to the use of naloxone in methods of eating disorder

therapy.

Description of Related

Art

[0002] Various eating

disorders, including binge eating, bulimia, and stimulus-induced

over-eating, develop because the behaviors are reinforced by the opioidergic

system so often and so well that the person no longer can control the behavior.

Thus eating disorders resemble opiate addiction and alcoholism. Eating disorders

can-not, however, be treated effectively by continual daily ad-ministration of

opiate antagonists because normal healthy eating behavior is also reinforced by

the opioidergic system. Instead, a selective extinction method is needed

that weakens the eating disorder while strengthening healthy eating.

Extinction sessions in which the eating disorder responses are emitted while an

opiate antagonist blocks reinforcement must be interspersed with learning

sessions in which healthy eating responses are made while free of antagonist. In

between extinction and learning sessions there must be a wash-out period in

which the antagonist is allowed to be eliminated from the body, and during which

neither problem eating nor healthy eating should occur. Consequently,

preparations with long-lasting antagonists such as naltrexone and nalmefene with

wash-out periods of a day or more are not suitable, but naloxone with a half

life of only about an hour is excellent. Naloxone cannot be taken orally.

In-stead it is administered transdermally or by nasal inhalation. This

provides additional advantages with eating disorders: the purging with bulimia

does not affect the dosage; the gastrointestinal tract is not further disturbed

by the antagonist administration; and altering eating responses does not

affect taking the medication.

[0003] Opioid antagonists have

been patented for inducing anorexia (Smith, US Patent 4,217,353, 1980; US

Patent 4,477,457, 1984), and they also have been patented for treating

anorexia (Huebner, US Patent 4,546,103, 1985). Both results are valid. The

antagonists can also reduce binge eating and also the purging associated

with bulimia, but normal eating, too. Narrowly limited experiments have

found evidence for each of these effects. When put into long term practice,

however, the different effects counteract each other and cause

complications. For example, as Smith pointed out, the only clinical trial

using naloxone for anorexia was inconclusive because they coupled the treatment

with giving a hyper-caloric diet (Moore et al., 1981).

[0004] Unfortunately, the

methods used and previously

proposed for the treatment of eating disorders are unable to separate these

various actions. Consequently, the antagonists have produced mixed clinical

results, have not received FDA or equivalent European approval

|

|

5 for

use with eating disorders, and currently are not being used clinically for

such purposes.

|

[0005] In contrast, in the

field of alcoholism and drug addiction treatment, I proposed a method in which

the antagonists specifically remove the addictive behavior

|

|

10

(Sinclair, US Patent 4,882,335, Nov. 21, 1989; US Patent 5,587,381,

Dec. 24, 1996; EP Patent 0 346 830 B1, May 11, 1995). Our double-blind

placebo-controlled clinical trial has shown naltrexone is effective when

used in ac-cord with this method but not when used

otherwise

|

|

|

15

(Heinälä et al., 2001). Similar results have been obtained in

nearly all trials (Sinclair, 2001). Naltrexone has been approved by the

FDA for use in alcoholism treatment in 1995 and in Finland in 1996. Going

one step further, I improved the method into a procedure of "selective

ex-

|

|

|

20

tinction" that not only removes alcoholism and drug ad-diction but

also enhances other competing behaviors (Sinclair, US Patent 5,587,381,

1996; Sinclair et al., 1994; Sinclair, 2001). Especially in Finland where

naltrexone is widely used in this selective manner, it

has

|

|

|

25

become a major factor in the treatment of alcoholism. [0006] Extinguished

responses can be relearned; in-deed they are relearned more readily than

they were learned the first time. Subjects can be advised after a given

period of treatment to refrain henceforth from

mak-

|

|

|

30 ing

the extinguished response ever again in order to avoid relearning, but

they cannot avoid all responses reinforced through the opioidergic system.

One solution, used in alcoholism treatment, is to continue taking

antagonist in-definitely whenever there is a risk of drinking, or in

this

|

|

|

35 case

of making the eating disorder response again. Alternatively,

selective extinction can be used to "trim" of-fending responses that are

beginning to arise again be-fore they become harmfully strong. Like

finger-nails, the growth of responses is a useful natural process but

can

|

|

|

40

become harmful when left uncontrolled. Thus individuals with a

predilection for developing overly-strong responses might

periodically review their current activities and then trim those responses

that were beginning to get too strong -- as casually and almost as easily

as we trim our nails.

|

|

|

45

[0007] Perhaps the

greatest technological quest in this field since the discovery of the

opioid antagonists has been for preparations that would cause the

antagonists to remain in the body for longer periods of time.

Naltrex-

|

|

|

50 one

and nalmefene have been preferred over naloxone not only because they can

be taken orally but also be-cause of their much longer half-lives. Various

slow-release methods for naltrexone and nalmefene have been developed

over the passed two decades to

provide

|

|

|

55

weeks or months of constant blockade. Alkermes Inc. has recently

received FDA approval for Vivitrol, a long-acting, injectable formulation

of naltrexone.

|

3

EP 1 681 057 B1

Summary of the

Invention

[0008] The present invention

relates to a new and alternative way of treating eating disorders based on

the use of naloxone.

[0009] The above explained

quest, utilizing antagonists having a prolonged action and activity in the

body, is consistent with the previously proposed methods for treating bulimia

and binge eating with opioid antagonists. Their imagined mechanisms of action

would work best if the antagonists were always present, thus eliminating

supposed problems of patient compliance.

[0010] The present invention,

however, contemplates alternating periods when an opioid antagonist blocks the

opioid system (during which the eating disorder behaviors are emitted) with

periods when the patient’s body is free of antagonist (during which normal

healthy eating behaviors are made).

[0011] The present invention

is, therefore based on the use of naloxone for the preparation of pharmaceutical

compositions for methods of treating eating disorders in mammals, including

human beings.

[0012] The method of treatment

preferred comprises "selective extinction". We have used a similar "selective

extinction" procedure extensively in treating alcoholism (Sinclair, 2001).

(Incidentally, there has been little problem here with compliance.

Alcoholics have difficulty complying if you tell them to refrain from

drinking. They do not have a problem, however, with obeying the instruction to

take a pill always before drinking.)

[0013] With alcoholics, we

include a wash-out period of about 48 hours for removal of the naltrexone.

During this time the patients should not drink alcohol and they also should not

engage in the alternative opioidergicallyreinforced behaviors that we wish

to strengthen. This is not a problem with alcoholism or drug

addiction.

[0014] In the case of eating

disorders, such long wash-out periods are not possible. For example, when

treating bulimia, the behavior we wish to extinguish is eating foods that

trigger bulimia. The alternative behavior we wish to strengthen is eating foods

that do not trigger bulimia. Obviously patients cannot be expected to avoid

both activities, that is, to refrain from all eating, for a 48 hour

wash-out period. Nalmefene is removed even more slowly.

[0015] Naloxone, however, has

a half-life of only 30 to 80 minutes in humans. A patient given naloxone on one

day would be free of it the following day.

[0016] The present invention

contemplates the use of the opiate antagonist naloxone for the preparation of a

pharmaceutical composition for the treatment of eating disorders. In particular

the present invention provides for the use of naloxone (or a similar opiate

antagonist having a half-life of less than about 2 hours, preferably less than

90 minutes).

[0017] In particular, the

present invention contemplates the use of naloxone in the formulation of a

pharmaceutical composition used in a method based on selective

extinction.

[0018] Particularly preferred

compositions are those which are suitable for transdermal or nasal

administration appropriate in a therapeutic method, utilizing the ability of

opiate antagonist to block positive reinforcement from

|

|

5

stimuli produced by highly-palatable foods, from purging, and from

anorexic behavior in order to extinguish bulimia and other eating

disorders while simultaneously strengthening normal healthy eating

behaviors and the consumption of foods conducive to

health.

|

|

|

10

[0019] The

subject suffering from one of these overly-strong eating disorder

responses makes the response repeatedly, in the presence of stimuli

similar to those to which the response had been learned, while active

quantities of naloxone are in his or her brain, thus

eventually

|

|

|

15

extinguishing the response and removing the desire to make the

response. These extinction sessions are separated by "learning

periods" when the subject is free of antagonist and can make other

responses but not the problem response, in order to restore the strength

of com-

|

|

|

20

peting responses. Thus the problem response is selectively

extinguished.

|

[0020] Considerable advantages

are obtained with the present invention.

[0021] The lifetime prevalence

of bulimia is 2.8 % for

|

|

25

women, and 5.7 % of women will show bulimia-like syndromes

(Kendler et al., 1992). The disorder was strongly influence by genetics,

with a heritability coefficient of 55 %. Comorbidity was reported between

bulimia and anorexia nervosa, alcoholism, panic disorder, generalized

anxiety disorder, phobia, and major

depression.

|

30

[0022] In most cases the

subject will suffer from several related problem responses: e.g.,

overly-strong eating responses for a dozen specific highly palatable food

items. Each will be extinguished separately. Further-

|

|

35

more, prior to extinguishing a particular response, the subject

will not be allowed to make that response for at least a week. The

resulting increased motivation to make the response after being deprived

of the opportunity ("deprivation effect") will assure that the subject

makes

|

|

|

40 that

response at the beginning of extinction and will in-crease the

effectiveness of extinction.

|

[0023] Depending upon the

severity and nature of the problem responses, provisions are made for using the

method within a treatment center, as an out-patient treatment, and as a

combination of the two.

45

Brief Description of the

Drawings

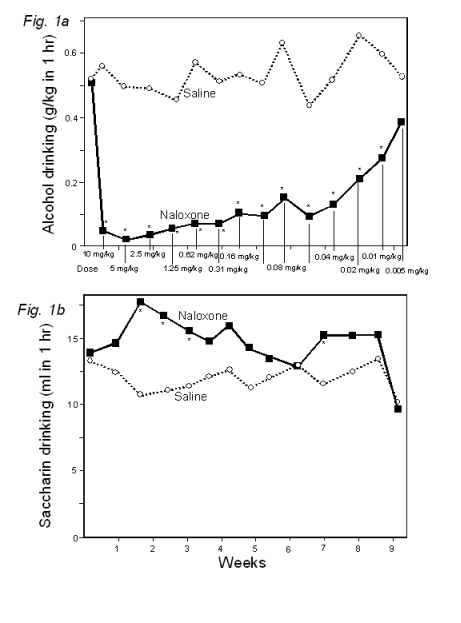

[0024]

50

Figure 1a

shows selective extinction (interspersing periods when alcohol was drunk daily

following naloxone injection with periods when saccharin was drunk with no

injection) strongly reduced alcohol

55 drinking,

while

Figure 1b

depicts increasing saccharin drinking in the same animals relative to intakes by

control animals injected with saline. Each data point is the

mean

4

5 EP 1 681 057

B1 6

of 1 to 4

days. The extremely low doses used from week 4 on have not previously been found

to be effective. * p<0.05 relative to saline controls.

Description of Preferred

Embodiments

[0025] The present invention

involves taking the selective extinction method for separating the actions

of opioid antagonists on different behaviors and contemplates applying it

to the treatment of eating disorders. Because the opioid antagonists

conventionally used in treating alcoholism are not suitable for treating eating

disorders, the present invention employs naloxone (or salts thereof) for use in

preparations that can be taken either transdermally or by nasal inhalation in a

manner suitable for selectively extinguishing eating disorders while reinforcing

healthy eating behaviors. In addition, several innovations are proposed to

optimize the method to the eating disorder field and which then differentiate

the method from all previously proposed treatments.

[0026] The key for how to

separate the actions of the antagonists comes from an understanding of how the

antagonists act in the nervous system to produce benefits.

[0027] There are two basic

processes through which long-term change is made in the organization of the

nervous system as a result of experience: one causes learning by

strengthening synapses; the other causes habituation and extinction by

weakening synapses (see Sinclair, 1981). Experimental results also show

that the two occur under different circumstances and follow different rules.

Thus, extinction is not simply learning to do some-thing else but rather a

separate phenomenon. It also is distinct from forgetting; it is an active

process for removing unsuccessful responses and requires the emission of

the response in the absence reinforcement.

[0028] Our preclinical

experimental results had shown that alcohol drinking is a learned behavior

(Sinclair, 1974), and that opioid antagonists suppress alcohol drinking by

mechanism of extinction (Sinclair, U.S. Patent 4,882,335, Nov. 21, 1989;

Sinclair, 1990). Extinction weakens only those responses that are made while

reinforcement is blocked. There the method I proposed for treating

alcoholism had the antagonist being administered just before the alcoholic

drank alcohol.

[0029] Others in the field,

however, believed that opioid antagonists block the craving for alcohol caused

by an imbalance, either a deficiency in opioid receptor activity (Tractenberg

and Blum, 1987; Volpicelli et al., 1990) or having too much opioid receptor

activity (Reid and Hub-bell, 1922). According to these theories, the antagonists

would be effective if given during abstinence; they would block craving and the

onset of drinking.

[0030] Our preclinical

experiments had shown that giving opioid antagonists during abstinence not

only failed to reduce subsequent drinking, but actually tended to in-crease

subsequent drinking above control levels (Sinclair et al., 2003). The same

result was found in our dual clinical trial

(Heinola et al., 2001). Naltrexone was effective when paired with alcohol

drinking, but naltrexone tended to be worse than placebo when given during

abstinence. Similar results can be seen in the other clinical trials

(Sin-

|

|

5

clair, 2001). The latest published count had 41 clinical trials

that obtained significant results from using opioid antagonists in a

manner allowing extinction; 37 trials using the antagonists in ways

precluding extinction, how-ever, got negative results; only 4 trials had

results con-

|

|

|

10

trary to this conclusion (Fantozzi and Sinclair, 2004). [0031] The mechanism

causing the increase in alcohol drinking when antagonists are administered

only during abstinence can be used to improve the efficacy of

treatment. It can increase the strength of behaviors other

than

|

|

|

15

alcohol drinking, of behaviors that can compete with drinking and

help fill the vacuum as drinking is extinguished. At the same time

other behaviors that are rein-forced by endorphins are protected from

extinction. One problem noted in some of the clinical alcohol trials is

a

|

|

|

20

reduction in the patients’ interest in sweets or

carbohydrates, or in sex (Bohn et al. 1994; Balldin et al., 1997).

This is probably caused by these behaviors being made while on naltrexone

and thus, along with alcohol drinking, being partially extinguished.

Naltrexone given to humans

|

|

|

25

reduces their preference for saccharin (Arbisi et al., 1999) [0032] The first step in

our clinical use of selective extinction in alcoholism treatment is

to have patients make a list of behaviors they find pleasurable. The

clinician identifies the behaviors on the list that are probably

re-

|

|

|

30

inforced by the opioidergic system and advises the patient to

avoid engaging in these activities on the days when taking naltrexone and

drinking. In the beginning of treatment, this is essentially every

day.

|

[0033] After the treatment has

reduced craving for al-

|

|

35

cohol, usually during the first month, the patient is advised to

have a weekend, starting with Friday evening, with no naltrexone and

drinking. Friday night and Saturday constitute a wash-out period for

naltrexone to be removed from the body. On Sunday afternoon, the patient

chooses

|

|

|

40 some

of the opioidergically-reinforced behaviors: eating a highly palatable

meal, jogging, having sex, cuddling, cards, etc. As expected, patients

usually report that the activities at this time are unusually

enjoyable.

|

[0034] The patients can return

to naltrexone and drink-

|

|

45 ing

on Monday. They are advised, however, to try the next week to have a

longer period without naltrexone and drinking but with the alternative

behaviors. A three-year follow-up showed that complying patients reported

a maximum of 1.5 ± 0.4 (SEM)

days per week (Sinclair et

|

50 al.,

2000).

[0035] The example included

here is a prior preclinical experiment

in which the alternative opioidergically-reinforced

behavior was saccharin drinking. Alcohol experienced rats

had continual access to food and water. Alcohol

solution was available for only an hour a day for 2 to 4 days.

On the next day or two, saccharin solution instead

was available. Naloxone (or saline for the control group) was

injected prior to the alcohol session. During

5

7 EP 1 681 057

B1 8

the first

three weeks when the naloxone doses were in the range previously found to be

effective, the alcohol drinking was practically abolished. Saccharin drinking in

the same animals was significantly increased.

[0036] The opioidergic system

reinforces responses, not only when activated by an opiate or alcohol, but also

when certain types of stimuli are experienced. The stimuli cause a release of

opioids in the brain, reinforcing the responses that produced these stimuli.

Consequently, opioid antagonists have been shown in clinical trials to be

effective in treating compulsive gambling (Kim, US Patent 5,780,479, 1998; Kim

et al., 2001).

[0037] Opioidergic

reinforcement is well documented for food-related stimuli. On the basis of a

large body of data, Cooper and Kirkham (1990, p. 91) concluded that "ingested

items provide stimuli which lead to the release of endogenous opioidergic

peptides in the central nervous system". The system does not appear to be

involved in the reinforcement from eventually obtaining calories, but rather

with that from the pleasant stimulation. For example, opiate antagonists reduce

sham feeding of sucrose, and they suppress the eating of chocolate-coated

cookies by rats, but not the intake of normal rat chow. Similarly in humans, the

antagonist nalmefene suppress-es intake of highly palatable foods but not that

of less pleasant tasting ones. Another general finding is that antagonists

suppress food consumption (and alcohol drinking) only in the later parts of

the first session or later parts of the first eating binge but not at the

beginning.

[0038] Other workers in the

field interpret these results differently than I do. They suggest that

"endogenous opioids play a central role in the modulation of appetite"

(Jonas, 1990). The opioids released by food-related stimuli block satiety

effects and make food stimuli continue to be pleasant even after caloric needs

have been satisfied; thus the opioid release "contributes to the

maintenance of ingestional behavior" (Cooper and Kirkham, 1990) and is

"involved with processes associated with continuance of eating rather than

starting to eat" (Wild and Reid, 1990). In some people the opioid release is too

large or too long, and thus they do not stop eating (or alcohol drinking)

normally but rather have "out of control" binges. An opiate antagonist blocks

this opioid action; therefore, so long as the antagonist is present the

duration of a binge is shortened. Similarly with alcohol drinking,

"antagonists at opioceptors [sic] would reduce the propensity to continue to

drink once drinking has begun" (Hubbell and Reid, 1990). Another interpretation

was made by Huebner (US Patent 4,546,103, 1985). He saw endorphins providing

satisfaction and pleasure from purging for bulimic patients and from anorexic

behavior. Blocking the opioid system with endorphins would re-move the reason

for patients making the behaviors, and thus help them to stop.

[0039] Both of these

interpretations are best served by continual opioid blockade. If endorphins

cause normal eating to expand to a binge, then continual blockade would

continually prevent binges. Or if endorphins provide the

pleasure from purging, continual naltrexone would suppress purging at all times.

Therefore others have not proposed using only short periods of blockade

interspersed with periods when the opioid system was

5 functional,

as is done with the present invention.

[0040] I see the results not

as immediate effects of the opioids and the antagonists on appetite or satiety,

but rather as aftereffects produced by learning and extinction. When a

highly palatable food is consumed, opioids

|

|

10 are

released and as a result, after consolidation, the response is

stronger. In some people the responses are reinforced so often and so well

that they become extremely strong and cannot be controlled properly.

When the response is emitted while an opiate antagonist

blocks

|

|

|

15 the

reinforcement, the response is weakened. The effect can be seen even

during the first session, not at the very beginning but reducing intake in

the latter portions and thus terminating a binge earlier. The antagonists

can re-duce purging if the behavior is emitted while

reinforce-

|

20 ment is

blocked because of extinction.

[0041] Opiate antagonists have

been tested for eating disorders but the methods used were ones that would be

appropriate if the antagonists worked by directly increasing satiety or

reducing appetite. In particular, the subjects

|

|

25 were

kept continually on the antagonists in order to pre-vent all eating from

getting out of control and turning into a binge. For example, Alger et al.

(1990) gave patients suffering from binge eating initially 50 mg of the

longer lasting antagonist, naltrexone, once daily, then twice

dai-

|

|

|

30 ly,

and if that did not work, 3 times daily, apparently for the purpose of

making sure the patient was never free of naltrexone. Although some

patients seemed to benefit, over all the naltrexone treatment was not

significantly better than placebo. Similarly, although some

uncon-

|

|

|

35

trolled studies found benefits from naltrexone in the

treatment of bulimia, the one placebo-controlled study did not

(Jonas, 1990). A recent review of pharmacological treatments for

binge eating does not include opioid antagonists among the medicines

for which there is clinical sup-

|

40 port

(Carter et al., 2003).

[0042] According to the

extinction hypothesis, keeping a person continually on the antagonist is not

optimal for treating eating disorders. In the case of binge eating, it weakens

not only the binge-eating response but also all

|

|

45

other emitted responses reinforced through the opioidergic

system. This makes the procedure less effective be-cause the probability

of binge-eating is determined not by its absolute strength but rather by

its strength relative to all competing responses. Of particular

importance, eat-

|

50 ing in a

healthy manner is also extinguished.

[0043] As discussed above, the

present invention instead

employs the "selective extinction" procedure (Sinclair, US

Patent 5,587,381, 1996) which has the person take an

antagonist only before making the problem re

55 sponse but

free of the antagonist at times when the problem

response is not made. Thus extinction sessions, when

mainly the problem response is weakened, are interspersed

with "learning periods" when other competing

6

9 EP 1 681 057

B1 10

response

including healthy eating responses can regain their strength. In the treatment

of bulimia, only binge-eating of specific highly palatable food is weakened, but

other competing responses are not.

[0044] Experimental support

comes from my studies with alcohol drinking: keeping rats continually on an

antagonist (large doses of naltrexone or nalmefene in the food)

significantly lowered alcohol drinking but did not reduce it as completely as

selective extinction produced by 1 hour sessions daily when alcohol and the

short-acting antagonist, naloxone, were present, as shown in the example

here.

[0045] Support may also be

seen in the fact that the only blind, placebo-controlled experiment with humans

to obtain significant results involving binge eating and opioid antagonists was

an acute study in which naloxone significantly reduced the size of an eating

binge (Atkin-son, 1982).

[0046] There are two other

advantages of selective extinction. First, the continual presence of an

antagonist produces up-regulation of opioid receptors (Unterwald and Zukin,

1990; Parkes and Sinclair, 2000). Consequently, a problem response would

produce more reinforcement after the end of antagonist treatment, than it

did before. Up-regulation should be attenuated with the selective extinction

procedure because the antagonist is present only for relatively short sessions

interspersed with antagonist-free periods.

[0047] Second, although opiate

antagonists are considered safe, there are side-effects, such as liver

toxicity with naltrexone, elevated cortisol levels, and possible

immunosuppressive effects (Morgan and Kosten, 1990). These side-effects

should be greatly reduced or eliminated with only periodic administration

of the antagonist. The dysphoria sometimes reported with continual

administration might also be caused by the general blocking of pleasure

from a wide range of activities, and should be less of a problem with selective

extinction where the per-son is free to enjoy opioidergic reinforcement from

other responses during the learning periods.

[0048] Selective extinction

can be used for treating a variety of eating disorders. In addition to bulimia

and binge-eating, it could be used as a dieting aid. A contributing factor

to obesity for many people is overly-strong eating responses and cravings for a

few highly palatable and high-energy foods: chocolate, cookies, peanut but-ter,

etc. Losing weight and then maintaining a normal weight would be possible after

these specific responses were removed by selective extinction. Similarly,

selective extinction could be used by people who are not necessarily

overweight but have to restrict their intake of a particular substance

(e.g., sugar or sodium chloride) that can be identified with a specific stimulus

that activates the opioidergic system. (There is evidence that both sweet and

salty tastes are reinforcing through this system (Levine et al.,

1982).)

[0049] The present invention

takes advantage of a relationship between opiate antagonists and a

phenomenon R. J.

Senter and I discovered called the "alcohol-deprivation effects" (Sinclair and

Senter, 1967). Taking alcohol away after prolonged prior experience gradually

over several days increases the desire for it. When it is

|

|

5 first

returned, intense drinking begins immediately, probably accompanied

by intensified pleasure and reinforcement. Deprivation effects also

develop for saccharin and specific highly-palatable foods, as well as for

many habitual behaviors. Opiate antagonists have been found

to

|

|

|

10 be

more effective in suppressing alcohol drinking after deprivation (Kornet

et al., 1990). The probable reason is that extinction (unlike learning) is

most effective with "massed trials", i.e., when the response is made over

and over again, vigorously, without pausing (see

Sinclair,

|

|

|

15

1981). Therefore, the extinction of specific eating responses

will generally be done after several days of deprivation of the

specific food item. For example, if chocolate ice cream is listed by

patients as a triggering food for bulimia, these patients will be told to

abstain from

|

|

|

20

eating chocolate ice cream, plus ice cream in general and chocolate

in general, for a week before taking an opioid antagonists and getting

unlimited chocolate ice cream to eat and

purge.

|

[0050] There is evidence

linking anorexia nervosa to

|

|

25 the

opioidergic system. First, it may develop from bulimia (Kassett and

Gwirtsman, 1988). Second, there is some preliminary evidence from a small

study showing for improvement of anorexia nervosa from treatment with

an opiate antagonist (Luby et al., 1987). Marrazzi and

Luby

|

|

|

30

(1986) suggested that starvation causes the release of endorphins;

anorexic patients starve themselves supposedly to get elation from

their own opioids. I suspect the situation is somewhat more complicated.

The specific anorexic behaviors may be reinforced by the opioid

sys-

|

|

|

35 tem,

but a major factor contributing to the condition is the extinction of

normal eating response. During the developmental phase, the patients

make all of the normal eating responses: going to the table, taking

the food, pushing it around with a fork, but then willfully withholding

the

|

|

|

40

responses of tasting and swallowing the food. Thus the preliminary

responses are made but do not get reinforcement from taste or from

removal of hunger, and as a result are extinguished. In any case, it is

clear that the solution is a strengthening of normal eating

behaviors,

|

|

|

45 and

extinction of the responses maintaining anorexia. This should be

accomplished by administering opioid antagonists while the patient is

not eating, interspersed with antagonist-free periods when the patient

does in fact eat a small amount of highly palatable

food

|

|

|

50

[0051] The

selective extinction method here for treating eating disorders

comprises selectively extinguishing the behaviors causing the disorder

while strengthening normal health eating behaviors. It preferably

comprises the steps of:

|

55

|

|

- repeatedly

administering naloxone in a dosage sufficient to block the effects of

opiate agonists to a subject suffering from an eating disorder caused

by one

|

7

11 EP 1 681 057

B1 12

or more

related problem responses;

|

|

-

while the amount of naloxone in the subject’s body is sufficient to block

opiate effects, having the subject make one of the problem responses from

which the subject suffers in the presence of stimuli similar to those to

which it had been learned,

|

|

|

-

after the amount of naloxone is no longer sufficient to block opiate

effects, having the subject make healthy eating responses to food items

that do not trigger the problem responses;

and

|

|

|

-

continuing the steps of administration of naloxone and having one after

another of the problem responses made, followed by having a

naloxone-free period in which healthy eating occurs, until the problem

responses are extinguished.

|

[0052] Based on the above, the

invention comprises, i.a., the following preferred embodiments:

In the

first, naloxone is used for the preparation of a pharmaceutical composition to

be Administered simultaneously with the patient making eating disorder

responses but in a manner so that effective levels of naloxone are not present

in the body when the patient makes healthy eating responses, and

continuing the alternating between extinction of eating disorder

responses with naloxone and reinforcement of healthy eating behaviors until the

eating disorder responses are weak enough to be controlled. Typically, in

the method, the patient makes said "healthy eating responses" a few hours,

preferably about 0.2 to 12 hours, in particular about 0.5 to 6 hours, typically

about 0.8 to 4 hours, after the first eating responses.

In a

second embodiment, naloxone is used transdermally and in a dose per day

amounting to about 0.001 mg to 50 mg.

[0053] The present invention

provides a means, or de-vice, suitable for the rapid, easy and foolproof

transdermal delivery of the opiate antagonist. The device is a package

containing a fixed dose of antagonist, a vehicle and a permeation enhancer to

assure rapid systemic de-livery of the antagonist. The package contemplated is a

container, such as a capsule, sachet, or squeeze tube, holding a fixed volume of

an ointment containing the antagonist, vehicle and enhancer. An important

consideration for the formulation that has not been mentioned previously is

the ease and rapidity of removing the transdermal composition and thus

terminating further naloxone administration.

[0054] For the transdermal

administration, naloxone can be in the form of the acid, the base, or the salts

there-of. The concentrations of naloxone in the ointment can range from 1 mg/ml

up to or in excess of the solubility limit of the vehicle. Possible vehicles

include propylene glycol, isopropanol, ethanol, oleic acid,

N-methylpyrrolidone, sesame oil, olive oil, wood alcohol ointments,

vaseline,

a triglyceride gel sold under the trade name Softisan 378, and the

like.

[0055] Possible permeation

enhancers include saturated and unsaturated fatty acids and their esters,

alco-

|

|

5 hols,

acetates, monoglycerides, diethanolamides and N, N-dimethylamides, such as

linolenic acid, linolenyl alcohol, oleic acid, oleyl alcohol, stearic

acid, stearyl alcohol, palmitic acid, palmityl alcohol, myristic acid,

myristyl alcohol, 1-dodecanol, 2-dodecanol, lauric acid,

decanol,

|

|

|

10

capric acid, octanol, caprylic acid,

1-dodecylazacycloheptan-2-one sold under the trade name Azone by

Nelson Research and Development, ethyl caprylate, isopropyl

myristate, hexamethylene lauramide, hexamethylene palmitate, capryl

alcohol, decyl methyl sulfoxide,

|

|

|

15

dimethyl sulfoxide, salicylic acid and derivatives,

N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide, crotamiton, 1-substituted

azacycloalkan-2-ones, polyethylene glycol manolaurate, and other

compounds compatible with the package and the antagonist, and having

transdermal permeation activity. In

|

|

|

20

accord with patent EPA-0282156, corticosteroid or other agents to

lessen skin irritation could also be included. A preferred vehicle is

propylene glycol and a preferred enhancer is linolenic acid (10

%).

|

[0056] Further details on

transdermal compositions 25 will

appear from US Patent No. 5,096,715.

[0057] In a third embodiment,

naloxone is given by intranasal inhalation and the dose per day is 0.001 mg

to 50 mg.

[0058] The intranasal

formulations can be formulated

|

|

30 with

naloxone in the form of the acid, the base, or the salts thereof together

with a stabilizer and a surfactant. Among pharmaceutically acceptable

surfactants the following can be mentioned: Polyoxyethylene castor

oil derivatives; mono-fatty acid esters of polyoxyethylene

(20)

|

|

|

35

sorbitan and sorbitan esters (TWEEN 20 and TWEEN 80),

polyoxyethylene monostearate (TWEEN 60), polyoxyethylene (20)

sorbitan monopalmitate (TWEEN 40), and polyoxyethylene 20 sorbitan

monolaurate (TWEEN 20); polyglyceryl esters, and polyoxyethylated kernel

oil.

|

|

|

40

Preferably, the surfactant will be between about 0.01 % and 10% by

weight of the pharmaceutical composition. [0059] The

pharmaceutically useful stabilizers include antioxidants, such as sodium

sulfite and metabisulfite, sodium thiosulfate and formaldehyde,

sulfoxylate, sulfur

|

|

|

45

dioxide, ascorbic acid, isoascorbic acid, thioglycerol,

thioglycolic acid, cysteine hydrochloride, acetyl cysteine,

hydroquinone, propyl gallate, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, butylated

hydroxytoluene, butylated hydroxyanisole, alpha-tocopherol and

lecithin. The stabilizer will

preferably

|

|

|

50 be

present in a concentration of about 0.01% and 5% by weight of the

intranasal composition.

|

[0060] Naturally, the

compositions may contain other components, as well (e.g. chelating agents and

fluidizing agents).

|

|

55

[0061] Each

of the above embodiments can be carried out by a method in which the dose

of naloxone is started at a high level of 5 to 50 mg and then is

progressively reduced over the days of

treatment.

|

8

13 EP 1 681 057

B1 14

[0062] By the above

embodiments, various eating disorders, typically selected from the group

comprising, binge eating, bulimia, bulimia-like syndrome, anorexia nervosa, and

habitual over-eating stimulated by specific stimuli including certain foods,

situations, or moods, can be successfully treated.

[0063] The method can also be

used in situations wherein the patient must lower intake of a particular class

of dietary substances including sodium chloride, sugars, cholesterols or

low-density cholesterols, and the responses to be selectively extinguished

are the eating of particular foods with high amounts of these substances. [0064] It should be noted that

the method can be used with subjects diagnosed as suffering from maladaptive

overly-strong responses reinforced by stimulation-induced release of

opioids and resulting in eating disorders. It cannot be used for patients

for whom the opiate antagonist is contraindicated. In particularly, patients who

are physiologically dependent upon opiates must be excluded.

[0065] Specific details for

the use of selective extinction with each of the different varieties of

problem responses are presented below. The initial steps, however, in each

case are similar. First, detailed information is obtained about the

patient’s responses: the particular responses that cause the patient

problems, the situations in which they have typically been emitted, and

particularly the foods that trigger the behavior. Second, the patient is checked

for alcoholism, drug addiction, or other contraindications. Third, if there

is any possibility of an active opiate addiction despite denials by the patient,

a small dose of opiate antagonist is administered under close medical

supervision.

[0066] Naloxone is metabolized

so rapidly in the liver that all of it is removed during the first pass after

oral administration. Consequently, it usually is injected, as was the case in a

previous test for treating anorexia (Huebner, US Patent 4,546,103,

1985).

[0067] Transdermal

administration of naloxone, how-ever, is much better suited for repeated

self-administration. I previously proposed a transdermal devise for

ad-ministering a fixed dose of an opioid antagonist, including naloxone, for use

in alcoholism treatment (Sinclair, US Patent 5,096,715, 1992). Recent

experiments (Panchagnula et al., 2001) have shown this devise with 33 %

propylene glycol as the vehicle and ethanol as the permeation enhancer

is even more effective for transdermal de-livery of naloxone than I had

anticipated: "theoretically blood levels well above the therapeutic

concentration of naloxone can be achieved" with a transdermal patch of a

convenient size. An intranasal spray has also been shown suitable for rapid

administration of naloxone for the majority of subjects and could also be used,

probably in combination with transdermal administration (Loimer et al.,

1992).

[0068] Avoiding the oral route

also has distinct advantages for selective extinction of eating disorders.

First, there is the problem that some of an orally administered medication

would be lost by purging, or not taken by anorexic patients. Second,

troubles with the gastrointestinal tract are common complications with eating

disorders. Oral administration itself irritates the throat and it

directs

|

|

5 the

highest concentration of the medication to intestines where it interacts

with opioidergically controlled motility. Third, the response of taking an

oral medication is similar to the eating responses we are trying to alter

with the treatment, thus adding a possible complication to the

pro-

|

10

cedure.

Binge-eating and

bulimia

[0069] Severe cases should be

handled initially in a

|

|

15

treatment center to assure compliance, to increase motivation,

to monitor health, and to provide counseling and training concerning

correct eating habits. The information obtained includes a list of the

patient’s "trigger foods", i.e., those highly palatable foods that

precipitate binges,

|

|

|

20 are

frequently included in binges, are greatly craved, or give the patient

intense pleasure when the first bite is eaten. A list is also prepared for

the patient of "healthy foods", i.e., nutritious foods that do meet any of

the above characteristics for trigger

foods.

|

|

|

25

[0070] The

patient is kept initially on diet specifically excluding a particular

trigger food and foods with similar characteristics for a week prior to

treatment. (In the afore-mentioned example, if the trigger is chocolate

ice cream, the patient avoids not only chocolate ice cream but

all

|

|

|

30 ice

cream and all chocolate.) Naloxone is then administered, perhaps

first by nasal spray and then transdermally, and then while active

quantities are present in the system, the patient is presented with the

trigger food and encouraged to have an eating binge of it. If possible,

the

|

|

|

35

situation in which the food is eaten should be similar to that in

which the patient usually has had eating binges. The response set should

also be similar; e.g., if the patient typically has purged after an

eating binge previously, purging should occur also in the extinction

session. No

|

40 healthy

foods should be available.

The

duration of an extinction session should match the patient’s previous binging

behavior. If binging normally continued for several days, the same should occur

in treatment, with additional transdermal administrations of

45 naloxone

being given as needed.

[0071] At the end of the

extinction session, the transdermal administration is stopped and the skin area

involved is washed thoroughly.

[0072] The extinction session

is followed the next day 50 by a

"learning period" of one day or more when no antagonist

is given and only healthy foods are available. Not only

are trigger foods not available, but also all stimuli related to

them; the patient should not see them or smell them, nor

should they be discussed in counseling. The

55 safe foods

can be restricted to meal times, but the patient can eat as

much as desired then: no attempt at dieting should

occur during the learning periods. Learning of alternative

behaviors can be encouraged, but care should

9

15 EP 1 681 057

B1 16

be used

with regard to responses reinforced through the opioid system. For example,

greater than normal intake of alcohol should not be allowed.

[0073] In subsequent

extinction sessions, the patient binges on other trigger foods that have not

been included in the previous sessions. In severe case being handled at a

clinical center, treatment continues until binge eating with most of the

patient’s trigger foods has been extinguished and the person has gained

greater control over his or her eating habits. Thereafter, an out-patient mode

of selective extinction treatment can be used. The subject is given take-home

doses of the opiate antagonist and told to take one whenever there is a high

probability that unsafe foods will be eaten in the next few hours. The

instructions state that the patients should go ahead and have an eating binge if

they feel like it, but only after taking naloxone. Under no circumstance should

they binge without taking the antagonist. The antagonist should not be taken

otherwise, i.e., when the patient thinks there is little chance of eating

trigger foods.

Dietary aid for

stimulus-bound overeating

[0074] An out-patient mode of

selective extinction is used for patients with less severe eating problems and

high motivation and ability for compliance. It can be used with subjects who are

obese or only moderately over-weight whose weight problem is not due to

glandular anomalies but rather is caused by eating more than more than caloric

needs in response to specific stimuli. The stimuli can be specific

highly-palatable ("trigger") food items, situations, or moods. Examples of

trigger food items would be chocolate, mayonnaise, peanut butter, potato chips,

cream, butter, and cheese. Examples of trigger situations are watching

television, fast food and other restaurants, parties, holidays, and "midnight

snack" excursions. Examples of moods are premenstrual syndrome (PMS),

post-traumatic stress (PTS), anxiety in anticipation of a stress situation,

and celebration euphoria. [0075] The procedure is the

same as that with binge-eating and bulimia except the subject is not kept in a

treatment center but rather conducts his or her own extinction sessions in

the outside world. The subject is given clear, precise instructions (similar to

those specified above for binge eating and bulimia) on how to extinguish the

problem eating responses (e.g., 1. create a list of trigger stimuli, 2. choose

one, 3. refrain from it for one week, 4. arrange for the trigger stimulus to be

present, 5. self-administer naloxone, 6. what to do during intervening

"learning periods" when the antagonist is not taken and the trigger stimuli

are avoided as much as possible.

Dietary aid for limiting

intake of specific substances (sugar, salt,

etc.)

[0076] Selective extinction

can be used for people who are not necessarily overweight but must reduce their

intake of a

particular substance that is closely associated with a distinct stimulus that

causes opioid release.

[0077] One example is with

people who need to reduce their intake of sodium chloride. Sodium chloride is

closely

|

|

5

associated with salty tastes, and there is evidence showing

that a salty taste produces reinforcement through the opioidergic system

(Levine et al., 1982). The person is given a series of extinction sessions

on naloxone and learning periods off of the antagonist. During the

extinc-

|

|

|

10 tion

sessions a variety of salty-tasting foods are eaten. If necessary, the

salty taste could be produced by a salt substitute, but sodium chloride

should be used if there is no medical danger from short-term intake of the

sub-stance. During the learning sessions, salty-tasting

foods

|

|

|

15 are

omitted from the diet completely. The responses of eating salty foods are

thus selectively extinguished, while the responses of eating non-salty

foods are not weakened and may be enhanced. This will reduce the

desire for salty foods and make it easier for the person to

stay

|

20 on a

low salt diet.

[0078] A similar procedure

could be used with people who need to restrict their intake of sugars. Sweet

foods are eaten during the extinction sessions and non-sweet ones during the

learning periods. The sweet taste could

|

|

25 be

produced with artificial sweeteners, but sugar should be used if there is

no medical danger from such limited

intake.

|

[0079] The method also can be

used with people who need to restrict their intake of cholesterols or

specifically

|

|

30

low-density cholesterols. Although there probably is no specific

taste stimuli associated with cholesterols, they tend to be present in

highest amounts in particular highly-palatable foods. Consequently, during

the extinction sessions the person eats these particular foods and

during

|

|

|

35 the

learning session the person eats foods with low amounts of cholesterol or

low-density cholesterols. [0080] This procedure

could be used either in a treatment center or on an out-patient basis

depending upon the person’s ability to comply and the severity of the

ail-

|

40 ment

requiring the dietary limitations.

Anorexia

nervosa

[0081] The patient is kept

continually on a transdermal

|

|

45 opiate

antagonist for a period (probably 2 days or more) while intravenous

nutrients are supplied. Naltrexone or nalmefene could be used initially

but naloxone should be used in the last

day.

|

[0082] Antagonist

administration is then abruptly ter-

|

|

50

minated. During the next day (a learning period when the system is

free of active levels of antagonist), the patient is given small portions

of a variety of highly-palatable foods and strongly encouraged to eat at

least a small amount. The rebound supersensitivity of the opioid

sys-

|

|

|

55 tem

should help to reinforce the eating responses that are

made.

|

[0083] The next day the

patient is placed again on the antagonists and fed intravenously. The pattern of

extinc-

10

17 EP 1 681 057

B1 18

tion

sessions and learning periods continues. New highly-palatable foods are

introduced on each antagonist-free day, with at least a week between duplication

of the same food item in order to allow deprivation effects to increase the

reinforcement. After the first sessions, in-creasing attention is paid to

providing a well-rounded, nutritious variety of highly-palatable foods.

Pharmacological potentiation of the opioidergic response, e.g., with

moderate amounts of alcohol, can be employed.

[0084] During extinction

session days on the antagonist, the patient is encouraged to make the most

common responses from his or her own list of previously-learned competing

anorexic responses (e.g., vigorous exercise) that are probably reinforced

through the opioid system. In most cases, the aim should be weakening these

responses only to a normal level.

EXAMPLE

[0085] Selective extinction:

weakening of one behavior and at the same time strengthening another. Selective

extinction is produced by pairing the response we want to decrease (alcohol

drinking by rats in this example) with an opioid antagonist and pairing the

response we want to become more powerful (saccharin drinking here) with times

when the antagonist is not in the body.

[0086] The example

demonstrates that selective extinction can be produced with naloxone (i.e.,

the antagonist best suited for treating eating disorders.) It also shows

that selective extinction works with eating behaviors like saccharin

drinking that are normally reinforced by the flavor causing endorphins to be

released.

Methods

[0087] Male Wistar rats (n=26)

were individually housed with daily access to 10 % ethanol, with food and water

always present. After 2 months prior experience, the rats were switched to

having 2-4 alcohol-access days interspersed with 1 or 2 days when saccharin

solution (1 g/l) was available for 1 hr. The rats were then divided into 2

matched groups, one always receiving a subcutaneous dose of naloxone prior to

alcohol access and a control group receiving a similar injection of saline prior

to alcohol access. No injections were made prior to saccharin access. In

addition, the naloxone dose was progressively reduced from 10.000 to 0.005

mg/kg.

Results

[0088] The naloxone injections

significantly reduced alcohol drinking in comparison with both the alcohol

in-take by the controls and in comparison with their own prior levels (see Fig.

la). The alcohol drinking continued to be significantly reduced for 8 weeks;

many of these weeks involved doses far lower than previously found to be

effective. Alcohol drinking was reduced to nearly zero for most rats for 6

weeks. The suppression of drinking of alcohol

drinking appears greater than in previous experiments in which both alcohol

drinking and antagonist ad-ministration occurred every day and specifically

greater than in studies aimed at maintaining a continual presence

|

|

5 of

the antagonist by using longer lasting naltrexone or nalmefene and mixing

them with the food.

|

[0089] In contrast to the

sharp reduction in alcohol drinking, saccharin drinking was consistently higher

in the naloxone treated rats than in the controls and signif-

|

|

10

icantly so during the first three weeks when doses of naloxone

previously shown to be effective were used (see Fig.

1b).

|

References

15

[0090]

"Naloxone

in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa: Effect on Weight Gain and Lipolysis" R.

Moore, I.H

|

20

|

Mills,

A. Forster, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1981, 74,

129-31.

|

"Targeted

Use of Naltrexone Without Prior Detoxification in the Treatment of Alcohol

Dependence: A Factorial Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial." P

|

|

25

Heinälä, H. Alho, K. Kiianmaa, J. Lönnqvist, K. Kuoppasalmi,

and J.D. Sinclair, Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 2001. 21,

287-292.

|

"Evidence

about the Use of Naltrexone and for Different Ways of Using It in the

Treatment of Alcohol-

|

30

|

ism"

J. D. Sinclair, Alcohol and Alcoholism 2001,36,

2-10.

|

"The Rest

Principle: A Neurophysiological Theory of Behavior" J. D. Sinclair, Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, 1981.

|

35

|

"Rats

Learning to Work for Alcohol" J. D. Sinclair, Nature 1974, 249,

590-592.

|

"Drugs to

Decrease Alcohol Drinking", J.D.Sinclair, Annals of Medicine, 1990, 22,

357-362.

"Alcohol

and Opioid Peptides: Neuropharmacologi-

|

|

40 cal

Rational for Physical Craving of Alcohol" M.C. Tractenberg, and K. Blum.

American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 1987,13,

365-372.

|

"Naltrexone

and the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence" J.R. Volpicelli, C.P.O’Brien,

A.I.Alterman, and

|

|

45 M.

Hayashida, In Opioids, Bulimia, and Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism,

L.D.Reid, ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990, pp

195-214.

|

"Opioids

Modulate Rats’ Propensities to Take Alcoholic Beverages" L. D. Reid, and C.

L. Hubbell, in

|

|

50 Novel

Pharmacological Interventions for Alcoholism. C.A. Naranjo and E.M.

Sellers (eds) New York: Springer-Verlag,

pp.121-134,1992

|

"Uso

Efficace del Naltrexone: Ciò Che Non è Stato Detto a Medici e Pazienti"

(Effective use of naltrex-

|

|

55 one:

What doctors and patients have not been told) D. Sinclair, F. Fantozzi,

and J. Yanai, The Italian Journal of the Addictions, 2003,

41,15-21.

|

"La

Ricaduta Nell’Alcol: un Concetto Vincente, Ma

11

19 EP 1 681 057

B1 20

in Via di

Estinzione?" F. Fantozzi, and D. Sinclair, Personalit Dipendenze 2004,10,

219-243. "Naltrexone and Brief Counselling to Reduce Heavy Drinking" M. J. Bohn,

H.R. Kranzler, D. Beazoglou, and B.A. Staehler, The American Journal on

Addictions 1994, 3, 91-99.

"A

Randomized 6 Month Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study of Naltrexone and

Coping Skills Education Programme" J. Balldin, M. Berglund, S. Borg, M.

Månsson, P. Berndtsen, J. Franck, L. Gustafsson, J. Halldin, C. Hollstedt, L-H.

Nilsson, and G. Stolt, Alcohol and Alcoholism 1997, 32, 325.

"The

Effect of Naltrexone on Taste Detection and Recognition Threshold" P.A. Arbisi,

C.J. Billington, A.S. Levine, Appetite 1999, 32, 241-249. "Long-Term Follow Up

of Continued Naltrexone Treatment" J. D. Sinclair, K. Sinclair, and H. Alho,

Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2000, 24, suppl.

182A.

"Double-Blind

Naltrexone and Placebo Comparison Study in The Treatment of Pathological

Gambling" S. W. Kim, J. E. Grant, D. E. Adson, and Y. C. Shin, Biological

Psychiatry 2001, 49:914-921.

"Basic

Mechanisms of Opioids’ Effects on Eating and Drinking", S.J. Cooper and T.C.

Kirkham, in Opioids, Bulimia, and Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism, L.D. Reid, ed.

Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990, 91-110.

"Naltrexone

and Bulimia: Initial Observations", J.M. Jonas, in Opioids, Bulimia, and Alcohol

Abuse & Alcoholism, L.D. Reid, ed., Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990,

123-130.

"Obesity,

Anorexia Nervosa, and Bulimia: A General Overview", K.D. Wild and L.D. Reid,in

Opioids, Bulimia, and Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism, L.D. Reid, ed.,

Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990, 3-21.

"Opioids

Modulate Rats’ Intake of Alcoholic Bever-ages", C.L. Hubbell and L.D. Reid, in

Opioids, Bulimia, and Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism, L.D. Reid, ed.,

Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990, 145-174.

"Using

Drugs to Manage Binge-Eating among Obese and Normal Weight Patients", S.A.Alger,

M.J.Schwalberg, J.M. Bigaoutte, L.J. Howard, and L.D. Reid, in: Opioids,

Bulimia, and Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism, L.D.Reid, ed., Springer-Verlag, New

York, 1990, 131-142.

"Pharmacologic

Treatment Of Binge Eating Disorder" W.P. Carter, J.I. Hudson, J.K. Lalonde,

L. Pindyck, S.L. McElroy, and H.G. Pope Jr., International Journal of

Eating Disorders 2003, 34, Suppl:S74-88. "Naloxone Decreases Food Intake in

Obese Hu-mans", R. L. Atkinson, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and

Metabolism, 1982, 55, 196-198.

"The

Endogenous Opioidergic Systems" E.M.Unterwald and R.S.Zukin, in, Opioids,

Bulimia, and Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism, L.D. Reid, ed.,

Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990, 49-72.

"Reduction

of Alcohol Drinking and Upregulation of Opioid Receptors by Oral Naltrexone in

AA Rats" J.H. Parkes

and J.D.Sinclair. Alcohol, 2000, 21, 215-221.

"Potential

Toxicities of High Doses of Naltrexone in Patients with Appetitive Disorders",

C.J. Morgan and

|

|

5 T.R.

Kosten, in Opioids, Bulimia, and Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism, L.D.

Reid, ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990,

261-273.

|

"Flavor

Enhances the Antidipsogenic Effect of Naloxone", A. S. Levine, S. S. Murray, J.

Kneip, M.

|

10

|

Grace

and J. E. Morley, Physiology and Behavior, 1982, 28,

23-25.

|

"Increased

preference for ethanol in rats following alcohol deprivation", J.D. Sinclair,

and R.J.Senter, Psychonomic Science 1967, 8, 11-12.

|

|

15 "The

Effect of Naltrexone on Alcohol Consumption after Alcohol Deprivation in

Rhesus Monkeys", M. Kornet, C. Goosen, and J.M. Van Ree, Abstracts of the

XXth Nordic Meeting on Biological Alcohol Re-search, Espoo, Finland, May

13-15, 1990, abstract

|

20 20

"Pattern

of Onset of Bulimic Symptoms in Anorexia Nervosa", J.A. Kassett, H.E. Gwirtsman,

W.H. Kaye, H.A. Brandt, and D.C. Jimerson, American Journal of Psychiatry, 1988,

145, 1287-1288.

|

|

25

"Case Reports: Treatment of Chronic Anorexia Nervosa with

Opiate Blockade", E.D. Luby, M.A. Marrazzi, and J. Kinzie, Journal of

Clinical Psychopharmacolgy, 1987, 7,

52-53.

|

"An

Auto-Addiction Opioid Model of Chronic Anorex-

|

|

30 ia

Nervosa", M.A. Marrazzi and E.D. Luby, International Journal of

Eating Disorders, 1986, 5, 191-208. "Transdermal Delivery of Naloxone:

Effect of Water, Propylene Glycol, Ethanol and Their Binary

Combinations on Permeation Through Rat Skin" R.

Pan-

|

|

|

35

chagnula, P.S. Salve, N.S. Thomas, A.K. Jain, and P. Ramarao,

International Journal of Pharmacology 2001, 219,

95-105.

|

"Nasal

Administration of Naloxone is as Effective as the Intravenous Route in Opiate

Addicts" N. Loimer,

|

40

|

P.

Hofmann, and H.R. Chaudhry, International Journal of Addictions,

1994, 29, 819-827.

|

"The

Genetic Epidemiology of Bulimia Nervosa" K.S. Kendler, C. MacLean, M. Neale, R.

Kessler, A. Heath, and L. Eaves, American Journal of Psychia-

45 try,

1991,148, 1627-1637.

"Selective

Extinction of Alcohol Drinking in Rats with Decreasing Doses of Opioid

Antagonists" J.D. Sinclair, L. Vilamo, and B. Jakobson. Alcoholism:

Clinical and Experimental Research 1994, 18, 489.

50

Claims

1. Use of naloxone for the

preparation of a pharmaceu-

|

|

55

tical composition for treating eating disorders by a method based

on selective extinction comprising the

steps:

|

12

21 EP 1 681 057

B1 22

- identification of the

specific responses in the patient’s eating behavior that are unhealthy or

otherwise inappropriate,

-

administering the pharmaceutical composition containing naloxone just before the

patient 5

makes these unhealthy responses,

- having

the patient make healthy eating responses only when the effective levels of

naloxone are no longer present in the body, and

- having

the patient to alternate between making 10 unhealthy

eating responses when effective levels of naloxone are present and making

healthy eating responses when effective levels of naloxone are not present, so

long as the patient

still

wants to make the unhealthy eating respons 15

es.

|

2. Use

according to claim 1, wherein the eating disorder is selected from the

group comprising binge eating, bulimia, bulimia-like syndrome, anorexia

nervosa, and habitual over-eating stimulated by specific stimuli

including certain foods, situations, or moods.

3. Use

of naloxone for the preparation of a pharmaceutical composition for

improving compliance among patients who must lower intake of a particular

class of restricted food including dietary substances such as sodium

chloride, sugars, cholesterols or low-density cholesterols by a

method based on selective extinction comprising the

steps:

|

20

25

30

-

administering the pharmaceutical composition containing naloxone just before the

patients eats the restricted food,

- having

the patient eat other non-restneted food 35 only when

the effective levels of naloxone are no longer present in the body,

- having

the patient alternate between occasion-ally eating the restricted food when the

effective levels of naloxone are present and eating non- 40 restricted

food when effective levels of naloxone are not present, so long as the patient

still wants to eat the restricted food.

-

Identifizieren der spezifischen Reaktionen im Essverhalten des Patienten, welche

ungesund oder anderweitig ungünstig sind,

|

Patentansprüche

1. Verwendung von

Naloxon zur Herstellung eines Arzneimittels zur Behandlung von

Essstörungen durch ein Verfahren beruhend auf selektiver Löschung,

umfassend die Schritte:

|

-

Verabreichen des Arzneimittels enthaltend Naloxon kurz bevor der Patient

diese ungesunden Reaktionen ausführt,

- den

Patienten dazu bringen, die gesunden Essreaktionen nur dann auszuführen, wenn

die wirksamen Spiegel von Naloxon nicht länger im Körper vorherrschen,

und

- den

Patienten dazu bringen, zwischen dem Ausführen von ungesunden Essreaktionen,

wenn wirksame Spiegel von Naloxon vorherrschen, und dem Ausführen von

gesunden Essreaktionen, wenn wirksame Spiegel von Naloxon nicht

vorherrschen, zu wechseln, so lange der Patient die ungesunden Essreaktionen

immer noch ausführen will.

|

4. The

use according to any of claims 1 to 3, wherein 45 naloxone

is given transdermally and the dose per day is 0.001 mg to 50

mg.

5. The

use according to any of claims 1 to 3, wherein naloxone is given by

intranasal inhalation and the 50 dose

per day is 0.001 mg to 50 mg.

6. The

use in accordance with any of the preceding claims, wherein the dose of

naloxone is started at a high level of 5 to 50 mg and then is

progressively 55

reduced over the days of treatment.

|

|

2. Verwendung

nach Anspruch 1, wobei die Essstörung ausgewählt ist aus Binge

Eating, Bulimie, bulimieähnlichem Syndrom, Anorexia nervosa und

gewohnheitsmäßigem Über-Essen stimuliert durch spezifische Stimuli

einschließlich bestimmter Nahrungsmittel, Situationen oder

Gemütszustände.

3. Verwendung

von Naloxon zur Herstellung eines Arzneimittels zur Verbesserung der

Therapietreue unter Patienten, welche die Aufnahme von einer

bestimmten Klasse an begrenzten Nahrungsmitteln herabsetzen

müssen, einschließlich Diätsubstanzen wie Natriumchlorid, Zucker,

Cholesterine oder LDLCholesterine, durch ein Verfahren beruhend auf

selektiver Löschung umfassend die

Schritte:

|

-

Verabreichen des Arzneimittels enthaltend Naloxon kurz bevor der Patient

das begrenzte Nahrungsmittel isst,

- den

Patienten dazu bringen, andere, nicht-begrenzte Nahrungsmittel nur dann zu

essen, wenn die wirksamen Spiegel von Naloxon nicht länger im Körper

vorherrschen, und

- den

Patienten dazu bringen, zwischen dem gelegentlichen Essen des begrenzten

Nahrungsmittels, wenn wirksame Spiegel von Naloxon vorherrschen, und dem

Essen von nicht-begrenzten Nahrungsmitteln, wenn wirksame Spiegel von

Naloxon nicht vorherrschen, zu wechseln, so lange der Patient das begrenzte

Nahrungsmittel immer noch essen will.

13

23 EP 1 681 057

B1 24

|

4.

|

Verwendung

gemäß einem der Ansprüche 1 bis 3, wobei Naloxon transdermal verabreicht

wird und die Tagesdosis 0,001 mg bis 50 mg

beträgt.

|

5

|

5.

|

Verwendung

gemäß einem der Ansprüche 1 bis 3, wobei Naloxon durch intranasale

Inhalation verabreicht wird und die Tagesdosis 0,001 mg bis 50 mg

beträgt.

|

|

6.

|

Verwendung

gemäß einem der vorangegangenen 10

Ansprüche, wobei die Dosis an Naloxon bei einem hohen Spiegel von 5

bis 50 mg gestartet und dann allmählich über die Tage der Behandlung

reduziert wird.

|

-

administrer la composition pharmaceutique contenant la naloxone juste avant que

le patient n’ait ces réponses morbides,

- faire

que le patient ait des réponses alimentaires saines seulement lorsque les

taux efficaces de naloxone ne sont plus présents dans le corps,

et

- faire

que le patient alterne entre manger occasionnellement des aliments

interdits lorsque les taux efficaces de naloxone sont présents et manger des

aliments non interdits lorsque les taux efficaces de naloxone ne sont plus

présents, tant que le patient veut encore manger les aliments

interdits.

15

Revendications

|

1.

|

Utilisation

de naloxone pour la préparation d’une composition pharmaceutique pour le

traitement de troubles alimentaires par un procédé basé sur une extinction

sélective comprenant les étapes de

:

|

-

identifier les réponses spécifiques dans le comportement alimentaire d’un

patient qui sont morbides, ou inappropriées,

-

administrer la composition pharmaceutique contenant la naloxone juste avant que

le patient n’ait ces réponses morbides,

- faire

que le patient ait des réponses alimentaires saines seulement lorsque les

taux efficaces de naloxone ne sont plus présents dans le corps,

et

- faire

que le patient alterne entre les réponses alimentaires morbides lorsque les taux

efficaces de naloxone sont présents et des réponses alimentaires saines

lorsque les taux efficaces de naloxone ne sont plus présents, tant que le

patient veut encore avoir des réponses alimentaires

morbides.

|

2.

|

Utilisation